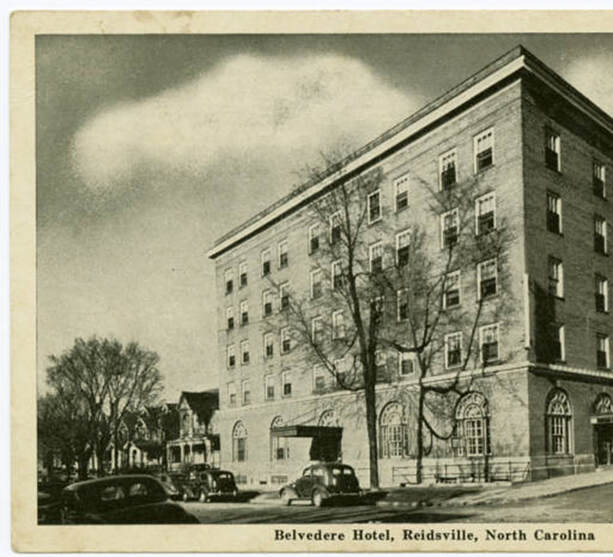

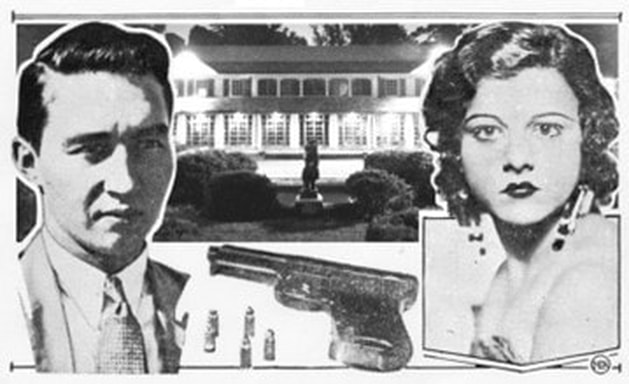

August 1932In the summer of 1932, Rockingham County found itself involved in a sensational celebrity news story when accused murderer Libby Holman Reynolds turned herself in at the Rockingham County Courthouse. The Broadway starlet was in Wentworth for only about two hours on a fiercely hot August afternoon, but her presence and the circumstances surrounding the death of her millionaire husband meant that her surprise arrival in Reidsville the night before and the location of her surrender to authorities were mentioned in news articles all over the nation. In the early morning of July 6, 1932, Z. Smith Reynolds, 20-year-old heir to the R. J. Reynolds tobacco fortune, suffered a gunshot wound to the head at Reynolda House, the family mansion in Winston-Salem, and died about five hours later at NC Baptist Hospital. Was it suicide, an accident, or murder?  (Above: As a Broadway star, Libby Holman was known for her seductive appearance and singing voice. Image from Wikimedia Commons) (Above: As a Broadway star, Libby Holman was known for her seductive appearance and singing voice. Image from Wikimedia Commons) At first, the death was called a suicide. His widow, Libby Holman Reynolds, told officials that Smith had killed himself after a party on the grounds of the estate. The young millionaire had threatened suicide several times before, his wife said. Dr. Fred Hanes, hospital physician who attended the victim, officially deemed the death a suicide and most of the Reynolds family seemed to accept this determination. Local authorities investigating Reynolds’ death, however, saw many contradictory details in accounts of the party the evening before the shooting, the hours at the hospital, and the discovery of the gun. Both Libby and Smith’s friend Albert (Ab) Walker, age 19, came under suspicion, and Forsyth County Sheriff Transou Scott called for further inquiry. A private coroner’s inquest was held. A distraught Libby testified only that she saw Smith with the gun to his head and saw a flash but remembered nothing else about the shooting or the evening leading up to it. The more testimony officials gathered, the more muddled the evidence seemed. Where was the bullet? Why was the gun not seen the first three times the scene of the shooting was examined but was clearly lying on the edge of the rug near the door the fourth time investigators entered the sleeping porch where Smith Reynolds was shot? Although local officials had many lingering questions about the possible involvement of both Libby and Ab, neither was detained. The inquest jury vaguely stated their verdict that Reynolds had died “from a bullet wound inflicted by a party or parties unknown.” The Sheriff saw the death as unsolved and continued the investigation. During the last week of July, the grand jury was convened. On August 4, they indicted both the widow and the lifelong friend on charges of murdering the young millionaire, charging that the pair “did unlawfully, willingly, feloniously, and premeditatedly of malicious forethought, kill and murder one Z. Smith Reynolds.” Ab was picked up almost immediately and taken to the jail in Winston-Salem. Libby, however, had left North Carolina with her family and gone back to Ohio about three weeks earlier. When authorities looked for her there, she had disappeared. It was later revealed that Libby was able to elude law enforcement and the media by shuttling between homes along the Chesapeake Bay connected to her millionaire friend, Louisa Carpenter. A month after the shooting, on Wednesday, August 8, the 26-year-old widow, Libby Holman Reynolds, surrendered to the Rockingham County sheriff in Wentworth at the county courthouse (now the building housing the MARC). She and her lawyers apparently chose Wentworth thinking it might be out of the limelight. There the judge handling the case, A.M. Stack, was hearing cases for a week, and the setting in the quiet rural county seat of Wentworth would possibly allow Libby to briefly appear, obtain bail, and move back to her undisclosed hideaway. As for media coverage, Wentworth seemed like a good choice because it had “no railroad, no telegraph facilities and only one telephone line,” according to a Holman biographer. Even in a village courthouse, however, these legal proceedings were not likely to be out of the public eye. Not only did the case involve perhaps the wealthiest family in North Carolina, but Libby was also a celebrity in her own right, having appeared in successful Broadway shows to rave reviews. She had developed a significant following as a “husky-throated” Broadway singer of blues and torch songs in New York City. One admirer was Smith Reynolds, the youngest of the four children of tobacco company founder, R. J. Reynolds, Sr. Smith first saw Libby in a production in Baltimore and then pursued her on tour in the U.S. and on trips abroad with her theater friends. As an aviator who owned his own plane, Smith Reynolds was able to fly across the U.S. and to Europe in pursuit of the “raven-haired stage beauty.” Libby was Reynolds’ second wife, having married Smith only a short time after his divorce from Anne Cannon, and only seven months before his death.  (Above: Libby Holman in the courtroom of the Rockingham County Courthouse on August 8, 1932. Despite the intense heat of the day, she was covered from head to toe in a widow’s black outfit and veil, so opaque that many of the spectators were not certain that they had actually seen the famous Broadway star. Image from Wikimedia Commons) (Above: Libby Holman in the courtroom of the Rockingham County Courthouse on August 8, 1932. Despite the intense heat of the day, she was covered from head to toe in a widow’s black outfit and veil, so opaque that many of the spectators were not certain that they had actually seen the famous Broadway star. Image from Wikimedia Commons) Driven to North Carolina by Louisa Carpenter, the friend who had been helping her hide from the public, Libby arrived in Reidsville just hours before her court appearance and checked in at the Belvedere Hotel. She was met there by her brother and her father Alfred Holman, who was assisting in her legal defense. Around 2:30 on the afternoon of her surrender, Libby was driven the eight miles to the courthouse in Wentworth in a limousine. She waited before going into the courthouse a few yards across the road in the parlor of what is now Wright Tavern, when it was a hotel and the private home of Wentworth postmaster Numa Reid. There, the Rockingham County Sheriff Leonard M. Sheffield served the warrant for her arrest. Celebrity photographers, a newsreel crew, and scores of local spectators swarmed around the Rockingham County Courthouse that afternoon. An observer estimated those gathered there to number five hundred. One of those in the crowd that day was Wentworth teenager and future textile executive Dalton McMichael, who sold copies of the local newspaper, making a $10 profit. Women from a nearby church had their food items for sale just as they did for every court session, but with such a large crowd on a very hot day, sales were particularly brisk. Others sold drinks and food from wagons or stands on the grounds, while most just crowded around the red brick building to catch a glimpse of the glamorous singer, now embroiled in scandal. Reporting for the Reidsville Review, local journalist W.C. (Mutt) Burton wrote of the scene that the surrender of Libby Holman in Wentworth was “enough to keep a battalion of newspaper reporters in feverish action, all afternoon and far into the night.” Dressed all in black with her face heavily covered by a widow’s veil, Libby Holman moved quickly through a largely silent crowd and entered the courthouse, accompanied by her father and Reidsville physician Dr. M. P. Cummings. The physician was needed, because, as reporters had been told earlier by Mr. Holman, his daughter was pregnant with Smith Reynolds’ child. This fact and the shock of having lost her husband so tragically combined to make her health very fragile, he said.  (Above: The Belvedere Hotel in Reidsville, NC, circa 1915-1930. Libby Holman and a small entourage met there the evening before her appearance the next day before a judge at the Rockingham County Courthouse in Wentworth. Image from North Carolina Postcards, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill) (Above: The Belvedere Hotel in Reidsville, NC, circa 1915-1930. Libby Holman and a small entourage met there the evening before her appearance the next day before a judge at the Rockingham County Courthouse in Wentworth. Image from North Carolina Postcards, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill) The courtroom was extremely crowded. Libby appeared before the judge, but the prosecutors basically spoke of how weak their evidence was against her and agreed to $25,000 bail, the same as had been ordered for her co-defendant, Walker. One local attorney later ranted about the fact that the judge called Libby to the bench and allowed the accused murderer to sit at his desk and sign the required papers, a gesture the attorney considered totally inappropriate. As the singer and her entourage exited the building and drove back to Reidsville, reporters followed. After her appearance in Wentworth, Libby somehow was able to elude the reporters and photographers camped out back at the Belvedere Hotel overnight and slipped out around 2 a.m.--to an unknown destination. A November 1932 court date was set for the trial of Ab Walker and Libby Holman Reynolds, but after a letter from the Reynolds family saying that they would support such a move, all charges were dropped against the pair because of insufficient evidence. Over time, details about the circumstances surrounding the shooting of Z. Smith Reynolds continued to emerge and the public remained interested in the mystery of his death. Several accounts of an alcohol-fueled party in the hours leading up to the shooting became known. One biographer even claimed that, despite Prohibition laws still being in effect, a five-gallon keg of corn liquor bought from a local bootlegger was provided for the 11 party guests and that many in attendance, including Libby, were drinking heavily. Through research, biographers and journalists pieced together a narrative of events. Libby, Ab, and another house guest, Blanche Yurka, a theater friend of Libby’s, had brought Smith Reynolds to NC Baptist Hospital on the night of the shooting. Investigators were told that Ab had first called an ambulance, but because it had not yet arrived, he had pulled the unconscious Smith from the sleeping porch, across the gallery, and down the steps, aided by Libby and then Blanche. The three then drove to the hospital in Libby’s car, with Blanche in the back seat, cradling Smith’s head. Ab drove and Libby, wearing only a peach-colored negligee, sat in the front. Reportedly, a nurse later helped the distraught wife into a robe to cover herself while Libby, Ab, and Blanche waited on the fifth floor of the hospital. Around 1:10 a.m., Smith Reynolds had been brought into the hospital, where doctors determined that the young man, unconscious the entire time, was not going to make it. He died at 5:25 a.m. In another tie to Rockingham County, one of the first two physicians to examine Reynolds was 26-year-old intern, Dr. Alexander M. Cox, who moved to Madison the next year and practiced medicine there for four decades. Although he was not interviewed by authorities at the time of the shooting, Cox told a biographer of Libby Holman in the 1980s that, because of the location of the entry and exit wounds, he believed that Smith Reynolds had been shot from some distance away and that it was not, then, a suicide. Ninety years later, it is still not clear who shot Z. Smith Reynolds. Financial matters, however, were settled within months, with Libby and her son, Christopher, who was born in January 1933, receiving about seven million dollars from the Reynolds estate. Libby lived the rest of her life under a cloud of suspicion, but over time did return to performing and used much of her money to fund philanthropic causes. The day Libby Holman Reynolds surrendered in Wentworth was notable in local history for the headlines it generated across the nation. Noting that the crowd gathered at the courthouse was both interested and sympathetic, reporter Dick Wilson summed up that August afternoon as “quite a gala day in Rockingham County,” “touched with … sincere sadness.” Recordings of Libby Holman are readily available online. Listen to two of her signature tunes, “Moaning Low” and “Body and Soul,” on YouTube below:

References

Jon Bradshaw, Dreams That Money Can Buy: The Tragic Life of Libby Holman (New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1985) Quoted from Bradshaw: shooting aftermath and hospital scenes, 117-123 (based on 309-page transcript of coroner’s inquest), coroner’s inquest and grand jury, 148, 156; Cox account, 152; Wentworth and media, 163; Hamilton Darby Perry, Libby Holman: Body and Soul (Boston and Toronto: Little, Brown and Company, 1983), in particular Chapters 22 and 23, 173-187; One of the causes funded by Libby Holman was Martin Luther King, Jr.’s trip to India in the late 1940s, where he studied the methods of Gandhi, nonviolence, and passive resistance. See also The Christopher Reynolds Foundation, Inc. https://creynolds.org/about-us/; “Image from Winston-Salem Journal, “Tragic Pairing of Tobacco Heir and Torch Singer,” Blog, North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, https://www.ncdcr.gov/blog/2014/11/29/tragic-pairing-of-tobacco-heir-and-torch-singer; Image of Belvedere Hotel, circa 1915-1930, North Carolina Postcards, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill, https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/nc_post/id/4425; Dick Wilson, “Libby Holman Creates Furor at Wentworth,” Leaksville News, August 11, 1932, 1 (“sincere sadness” quotation); Meredith Barkley, “On Call: Cox Lived To Doctor,” Greensboro (NC) News & Record, November 2, 1993, https://greensboro.com/on-call-cox-lived-to-doctor/article_34083080-dd54-5632-bbc0-5f3f330a31ed.html; Meredith Barkley, “Big Day: When Libby Holman Surrendered,” Greensboro (NC) News & Record, August 4, 1992, https://greensboro.com/big-day-when-libby-holman-surrendered/article_854969a9-765f-5536-89d8-ac2cad3f598d.html#:~:text=She%20finally%20surrendered%20in%20Wentworth,by%20two%20carloads%20of%20reporters; Articles from The Reidsville Review, Reidsville, NC: ”Smith Reynolds Kills Himself,” July 6, 1932, 6; “Youth’s Guardian Holds to Suicide Theory: Guardian Sure Reynolds Took His Own Life,” July 8, 1932, 1; “Smith Reynolds Inquiry Is Resumed Today: Seek Answer to the Question,” July 11, 1932, 1; “Will This State Get Reynolds Inheritance Tax,” July 11, 1932, 1; “Belvedere Is under New Management,” July 11, 1932, 1; “Smith Reynolds’ Widow Quits Winston-Salem,” July 13, 1932, 1; “Ann Cannon Is in Spotlight Again,” July 13, 1932, 1; “Jury Verdict in Reynolds Death Very Indecisive,” July 13, 1932, 1 (“raven-haired” quotation); “Sensations End Suddenly at the Twin-City,” July 15, 1932, 1; “Sheriff Scott Thinks Reynolds Was Slain: Is Convinced That It Was Not Case of Suicide,” July 18, 1932, 1; “The Reynolds Estate Still Is Unsettled,” July 22, 1932, 1; “Reynolds Case Has New Twist,” July 22, 1932, 1; “Holman Critical of Reynolds’ Case Probe: Sends Officers Telegram About Whole Affair,” July 25, 1932, 1; “Libby Holman Seeks To Settle Large Estate,” July 25, 1932, 1; “Libby Holman and Ab Walker Are Indicted: Walker Jailed, Seek Widow in Reynolds Case,” August 5, 1932, 1; “Holman Keeps Daughter Hid,” August 5, 1932, 1; “Libby Holman Coming to Wentworth,” August 8, 1932, 1; William Burton, “Libby Again Fades from the Public Gaze: Leaves Here with Brother and a Friend,” August 10, 1932, 1 (“feverish action” quotation); “Accused Torch Singer Has Been in Maryland,” August 10, 1932, 1; “Libby Reynolds Snapped at Wentworth Court,” August 12, 1932, 4; “Date for Trial Is Not Yet Fixed,” August 12, 1932, 4; “Now Facing Murder Indictments,” August 15, 1932, 1; “Has Enough Evidence To Convict?” August 22, 1932, 1; “Dick Reynolds Returns to Winston-Salem: May Talk about the Death of His Brother,” August 24, 1932, 1; “Thinks Brother Was Murdered,” August 26, 1932, 1; “Exhume Body of Young Smith Reynolds: Autopsy Was Performed on August 23rd,” September 2, 1932, 1; and “Libby’s Trial To Be Delayed,” September 21, 1932, 1.

2 Comments

6/18/2023 01:59:05 am

Libby Holman - June 18

Reply

5/29/2024 12:39:07 pm

May 23rd was Libby Holman's birthday.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Articles

All

AuthorsMr. History Author: Bob Carter, County Historian |

|

Rockingham County Historical Society Museum & Archives

1086 NC Hwy 65, Reidsville, NC 27320 P.O. Box 84, Wentworth, NC 27375 [email protected] 336-634-4949 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed