|

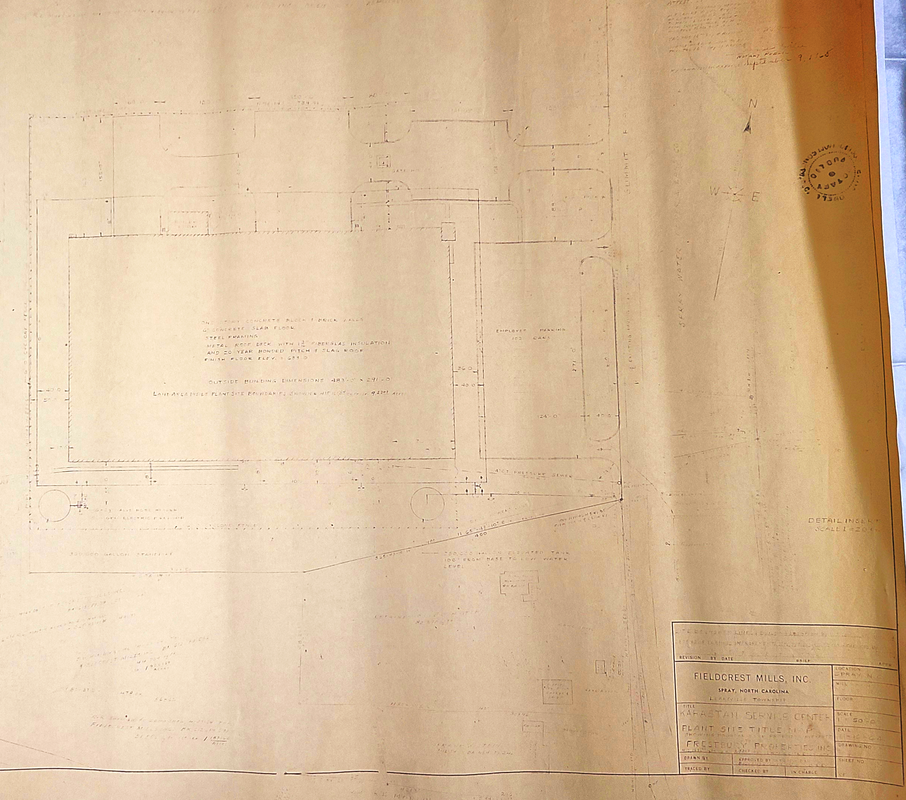

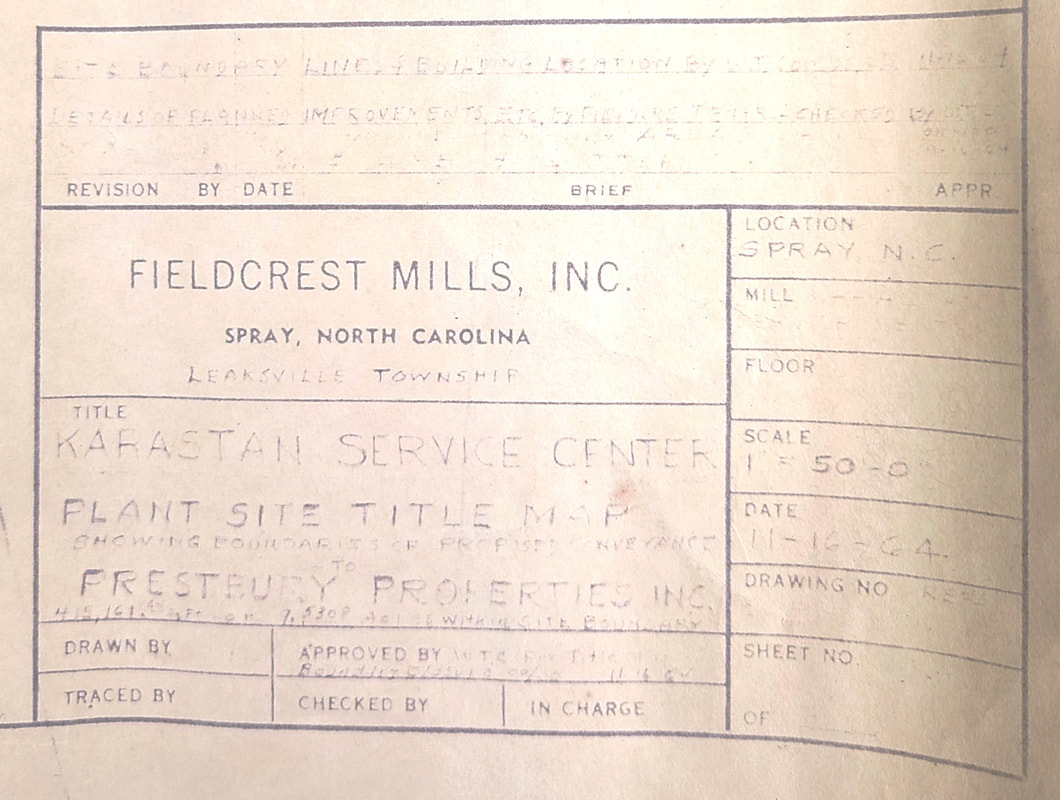

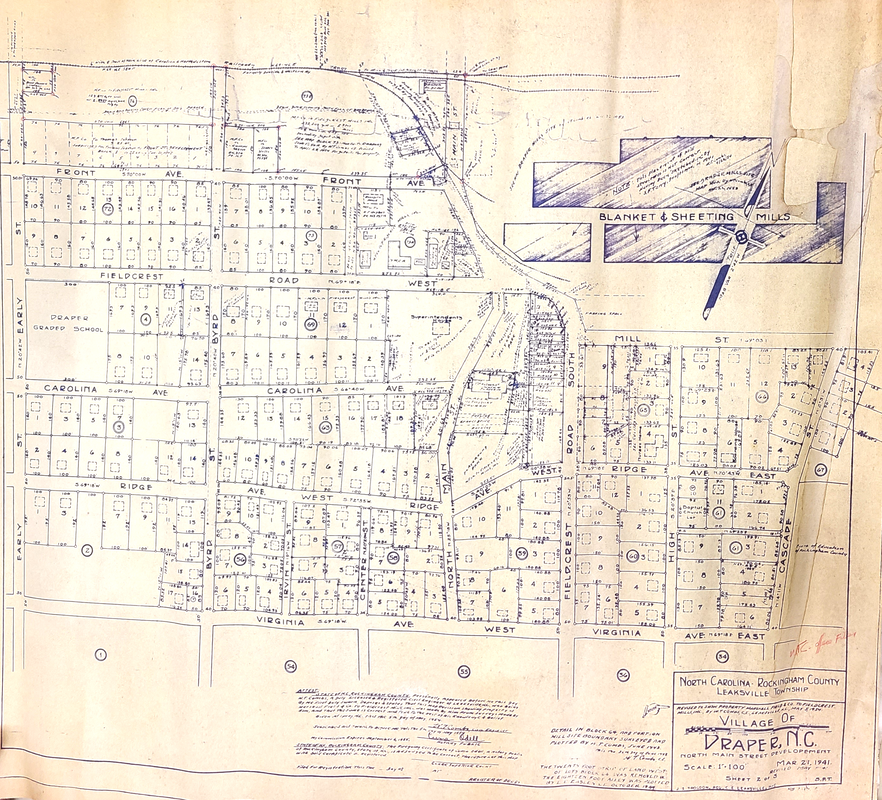

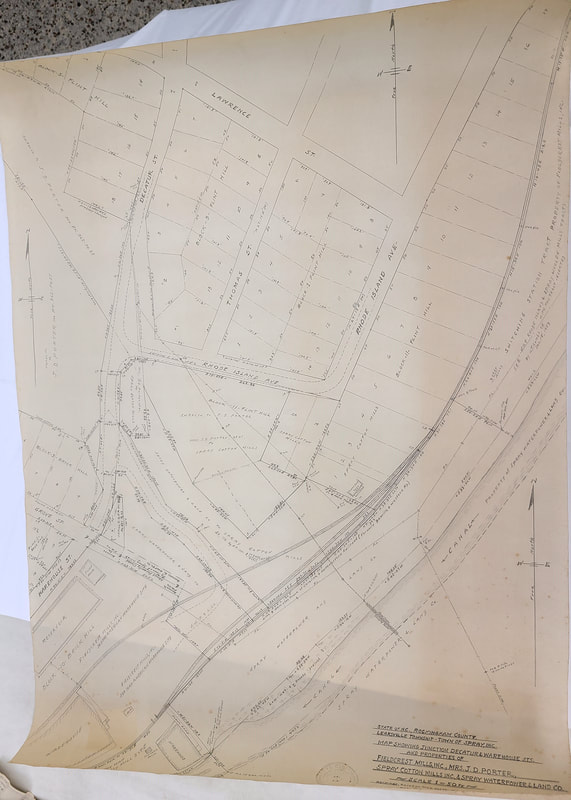

Mills heavily impacted the development of cities and towns throughout Rockingham County, and North Carolina more broadly. Historical maps allow some insight into the ways that these places looked throughout different points in time. Through historical maps, it is possible to learn about how interactions between the mills and the communities that were centered around them influenced one another and changed over time. John M. Morehead opened the Leaksville Cotton Mill in 1839.[1] It was one of the first textile mills opened in Rockingham County. In 1840, the Leaksville Cotton Mill employed 40 people, and by 1860, the census documented 80 women and 25 men working there.[2] Following the Civil War, Morehead would hire only white workers to work in his textile mill.[3] By 1890, there was a cotton mill in Reidsville, soon followed by Mayo Mills at Mayodan, the Spray Cotton Mill, and the mill at Avalon, which burned down in 1911, and was never reconstructed.[4] Benjamin Franklin Mebane would oversee the establishment of a number of additional mills in the late 1800s and early 1900s, including the Nantucket Mill, American Warehouse, and Lily Mill, among several others. Mebane had established so many mills that he did not have the money to fund all of them properly and Marshall Field and Company ended up taking control of his mills.[5] In the early 1900’s, one of the mills in Draper was owned by the German-American Co. in an area referred to as “the Meadows.” In 1912 the mill was purchased by the Marshall Field and Company, who also bought several of the mills in the surrounding area.[6] In 1953 Marshall Field and Company sold all of their mills in Rockingham County to Fieldcrest Mills, Inc.[7] Entire cities in Rockingham County were developed due to their proximity to a textile mill. The town of Draper is an example. Following the construction of the mill, the Rockingham Land Company sought to develop the town, a railroad was constructed, schools opened, churches were established, and the Bank of Draper was opened in 1920. Draper incorporated just under 50 years after the construction of the mill, in 1949.[8] The importance of the textile mills to the populace of Rockingham County historically cannot be overstated. The 1962 Hill’s Leaksville, Spray and Draper (Rockingham County, N.C.) City Directory refers to the mills as the “economic backbone of the Tri-Cities.”[9] Additionally, a 1977 report on the community by the County’s library reported that such a large percentage of the population of Rockingham County was employed in the textile industry that any economic downturn regarding textiles on a national level “would adversely affect Rockingham County’s entire economy.”[10] Evidence of the importance of mills to the county can be seen in many of the historical maps that are in the possession of the MARC. Of particular interest is a collection of several hundred maps that were originally owned by the Rockingham County government, which are largely maps made by engineers, for the purpose of delineating land ownership, rather than maps used for navigation or other purposes. Several of these maps include textile mill sites, including the Nantucket Mill site and the Spray Cotton Mill site, as well as several other non-mill properties owned by Fieldcrest Mills, Inc. These maps offer a unique glimpse into the past, which provide a visual framework for understanding the reach of the mills in various communities in Rockingham County, and the impact that textiles made in these local mills had on broader culture. One example of this is the map of the Karastan Service Center, owned, at the time, by Fieldcrest Mills, in Spray. The map dates from November 16, 1964. The Karastan Mill in Eden closed down operations in 2021, after 93 years of operation.[11] The Karastan Mill was a long term mainstay in Spray, and then Eden, outlasting many of the other mills in the area. Throughout its history, it was owned by Marshall Field & Co., Fieldcrest Mills, and Mohawk Industries. Karastan rugs are well known, and this mill shows how Eden has had a national influence. There are several other mills that are depicted in this map collection. With a slightly larger focus, another map is titled Junction of Decatur and Warehouse Streets and Properties of Fieldcrest Mills, Inc., Mrs. J.D. Porter, Spray Cotton Mills, Inc., and Spray Water Power and Land Co. Also owned by Fieldcrest Mills at times, this map was created in December of 1964. Spray Cotton Mills was originally a part of the Spray Water Power and Land Co., which was started by James Turner Morehead in 1889. Soon after the development of Spray Water Power and Land Co., James Turner Morehead shifted control of the company to B. Frank Mebane and W. R. Walker, who constructed the Spray Cotton Mills in 1896.[12] The following year, the Spray Cotton Mills were sold to Karl von Ruck, who is best known for studying and helping to create the tuberculosis vaccine.[13] The Spray Cotton Mills eventually closed down after 100 years in 2001. In January of 2023, a fire completely burned the main building in this complex. The mill was being sold or renovated for new uses when the fire broke out. [14] Both the map of Karastan Mills and Spray Cotton Mills are from 1964, just three years before Spray, Draper, and Leaksville merged to become Eden, a time of change for the community. The historical maps of Rockingham County depict important developments in communities and can provide important insights into the county’s textile mill history. Footnotes: [1] Hill’s Leaksville, Spray and Draper (Rockingham County, N.C.) City Directory (Richmond: Hill Directory Company, 1962), 17. [2] Lindley S. Butler, Rockingham County: A Brief History, (Raleigh: North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources Division of Archives and History, 1982), 42-43. [3] Butler, 58. [4] Butler, Rockingham County: A Brief History, 60, 66, 79. [5] Butler, Rockingham County: A Brief History, 79. [6] Hill’s Leaksville, Spray and Draper (Rockingham County, N.C.) City Directory, 18 [7] Butler, Rockingham County: A Brief History, 79. [8] Butler, Rockingham County: A Brief History, 72. [9] Hill’s Leaksville, Spray and Draper (Rockingham County, N.C.) City Directory, 18 [10] Rockingham County: The Library and the Community,” eds. Joyce Leeka, Deborah McCabe, and Deborah Russell, (Eden: Style-Kraft, 1977), 30. [11] Andrea Richards, “The End of the Wonder Rug,” New York Times, June 5, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/05/style/oriental-rugs-carpet-karastan-where-made.html. [12] Lindley S. Butler, “Spray Water Power and Land Company,” NCPedia, 2006. https://www.ncpedia.org/spray-water-power-and-land-company. [13] “Tuberculosis Vaccine Perfected in Asheville, 1912,” NC Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, November 5, 2016, https://www.ncdcr.gov/blog/2016/11/05/tuberculosis-vaccine-perfected-asheville-1912. [14] Susie C. Spear, “Sacred to Some, Only Ashes and Memories Remain After Spray Cotton Mills Fire,” Greensboro News and Record, January 27, 2023, https://greensboro.com/news/local/sacred-to-some-only-ashes-and-memories-remain-after-spray-cotton-mills-fire/article_d6e4911a-9dc5-11ed-96ec-47fa42a20e65.html Bibliography:

Butler, Lindley S. Rockingham County: A Brief History. Raleigh: North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources Division of Archives and History, 1982. Butler, Lindley S. “Spray Water Power and Land Company.” NCPedia. 2006. https://www.ncpedia.org/spray-water-power-and-land-company. Hill’s Leaksville, Spray and Draper (Rockingham County, N.C.) City Directory. Richmond: Hill Directory Company, 1962. Richards, Andrea. “The End of the Wonder Run.” New York Times, June 5, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/05/style/oriental-rugs-carpet-karastan-where-made.html. Rockingham County: The Library and the Community.” Eds. Joyce Leeka, Deborah McCabe, and Deborah Russell. Eden: Style-Kraft, 1977. Spear, Susie C. “Sacred to Some, Only Ashes and Memories Remain After Spray Cotton Mills Fire.” Greensboro News and Record, January 27, 2023, https://greensboro.com/news/local/sacred-to-some-only-ashes-and-memories-remain-after-spray-cotton-mills-fire/article_d6e4911a-9dc5-11ed-96ec-47fa42a20e65.html “Tuberculosis Vaccine Perfected in Asheville, 1912.” NC Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, November 5, 2016, https://www.ncdcr.gov/blog/2016/11/05/tuberculosis-vaccine-perfected-asheville-1912.

0 Comments

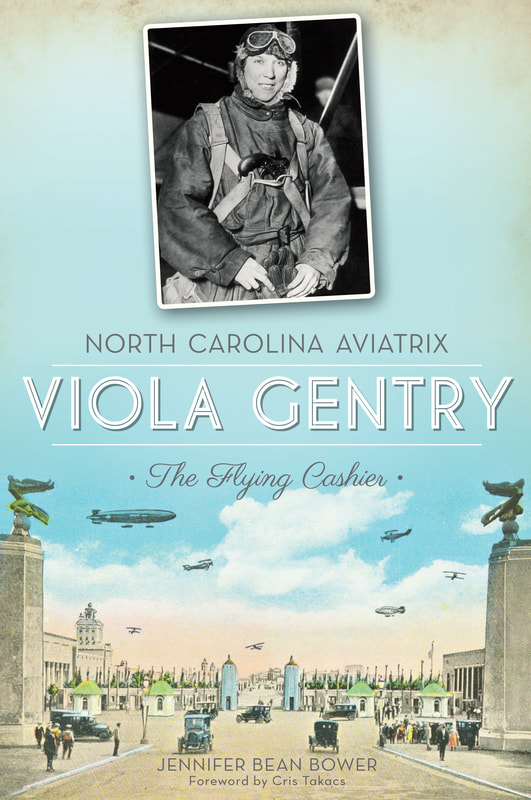

Viola Gentry of Rockingham County: America's "Flying Cashier" - Guest Article By Jennifer Bower12/15/2022 Foreword: Jennifer Bean Bower is an award-winning writer, native Tar Heel, and graduate of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and Wilmington. Bower is the author of North Carolina Aviatrix Viola Gentry: The Flying Cashier; Animal Adventures in North Carolina; Winston & Salem: Tales of Murder, Mystery and Mayhem; and Moravians in North Carolina. She lives in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, with her husband Larry and their pet rabbit Isabelle - and has been kind enough to write an article for MARC on Viola Gentry of Rockingham County. Viola Estelle Gentry was born in Rockingham County, North Carolina, on June 13, 1894, to Samuel and Nettie Walters Gentry. At the age of five, she and her younger sister Thelma were overcome by grief when their mother died. Several years later, the girls were saddened once again when Samuel moved the family to Danville, Virginia, and married Maydie Blanche Price. In Virginia, Viola endured a strained relationship with her stepmother and a monotonous job at a cigar factory. At the age of sixteen—in an effort to break free from the two—she ran away from home and attempted to join a circus in Greensboro, North Carolina. When that plan failed, Viola eloped with her boyfriend George Henry Gee. Soon after, likely at the behest of their parents, the marriage was dissolved and Viola was sent to live with an aunt and uncle in Jacksonville, Florida. The exact reason Viola was sent to Florida is unknown but it may have been to keep her separated from George, or to satisfy her cravings for adventure. Whatever the purpose, the journey to Florida was fortuitous as it was there she took her first flight. Unfortunately, Viola failed to ask her aunt and uncle for permission to take that flight and received a “sound spanking” when she landed. The flight, as well as the consequence of taking it, was an experience she never forgot. Following her daring jaunt through the clouds, Viola returned to Danville; but, she did not remain there long. In 1912, she was placed in the care of family friends—Mr. and Mrs. John Sears—who lived in Connecticut. The relationship between Viola and the couple was cordial and she credited them with providing her a good education. During the First World War, Viola supported the war effort by selling Liberty Bonds and working in an ordnance factory. When the war was over, she said good-bye to Mr. and Mrs. Sears; volunteered with the American Red Cross; traveled to San Francisco, California; secured a job as a switchboard operator; rented an apartment; and witnessed the event that changed her life. On a fateful day in July 1920, Viola watched in awe as Ormer L. Locklear, a Hollywood stunt pilot, landed his airplane on the roof of the tallest hotel in San Francisco. In one breathless moment, Viola’s destiny had been revealed. Her enthusiasm for aviation, an interest buried since her first flight in Florida, had been resurrected; and she would not let it be suppressed again. Viola declared that day—in that moment—that she would learn to fly. And, soon after, she did. Viola’s appetite for all things flight-related became insatiable. She attended lectures, read books, and saved money, to take her first flying lesson. When she finally had the amount needed, Viola arranged to meet a flight instructor at Crissy Field. However, her excitement to fly was dampened—albeit not extinguished—by the words of her male flight instructor who said “A woman should NOT fly, but should stay home, get married and raise a family.” Of course, Viola did not agree with those sentiments, so she packed her bags and headed to New York. She was convinced that the East Coast offered better opportunities for women interested in aviation and—at least in her regard—she was right. In 1924, while working two jobs, Viola learned to fly. The following year, she soloed; and in 1926, she flew underneath the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges. The stunt was front page news and Viola—who the press dubbed “the flying cashier” because of her position in a local restaurant—was an instant celebrity. Not everyone, however, was impressed with her aerial achievements. In fact, Viola’s parents felt her “activities were…unladylike” and that “she had disgraced the family.” Although Viola was likely disheartened by her family’s opinion, it did not stop her from flying. On December 20, 1928, she took off from New York’s Roosevelt Field in a Travel Air biplane and after “flying eight hours, six minutes, and thirty-seven seconds through winter weather,” Viola set the first officially recorded women’s solo endurance flight record. And, once again, her name, along with the story of her record-setting flight, was heralded in black and white.

Viola soared in the spotlight of an admiring nation and sought to achieve even greater feats. In 1929, she and John W. “Big Jack” Ashcraft endeavored to set a new refueling endurance flight record. The two intended to fly 174 hours or longer when they took off from Roosevelt Field on July 29, but fog and an empty fuel tank sent them to the ground. Ashcraft—who was at the controls—died instantly. Viola survived, but her injuries were so severe that she remained in a hospital for more than a year. Throughout her recovery and in the years that followed, Viola married—in secret because her fiancé’s family believed that women pilots were a disgrace to their gender—became a charter member of the Ninety-Nines; laundered clothes for Harold Gatty and Wiley Post when they flew around the world; supported women’s rights in aviation; presented lectures; and welcomed Amelia Earhart back to New York after her famous flight across the Atlantic. She competed in air races; helped preserve the history of early aviation; received numerous awards; and continued to fly until cataracts permanently grounded her in 1975. On June 23, 1988, at the age of ninety-four, Viola Estelle Gentry folded her wings. When she died, there were no large gatherings or grand speeches from famous men and women; yet, no words could have better defined her life than two sentences printed in the Danville Register & Bee. In her death notice, the author proclaimed that Viola “wanted to fly airplanes. And fly she did.” “And fly she did,” indeed. In the final year of World War I, a deadly outbreak of influenza (and the pneumonia that often accompanied it) hit North Carolina, ultimately taking 13,644 lives across the state. More than 700,000 died nationally. Many have expressed an interest in learning more about how this 1918 influenza epidemic, quickly becoming a pandemic, affected Rockingham County. Local historian Debbie Russell and author of our 'This Month in Rockingham County History' articles, has kindly stepped in to research the 1918 epidemic's toll on the County for our July newsletter article, as Bob Carter protects his health while staying at home. Thank you Debbie for your tireless efforts and thorough and fascinating research. How many more will die in this pandemic? How long will schools be closed? What can we do to stop the spread? Will my business survive? When will we get to return to church? These are all troubling questions that loom as we try to work through our current COVID-19 crisis. One hundred years ago, Rockingham County residents were facing some similar questions as they dealt with a devastating influenza outbreak—what has been called the 1918 Spanish flu. Because Spain was not involved in fighting WWI, the Spanish government did not withhold news of the influenza outbreak there as other countries did. And, because the public heard of the Spanish king’s bout with the flu early in the outbreak, many assumed the epidemic had started there. While there is still debate about the influenza’s origins, there is credible evidence that some of the earliest cases were identified by a doctor in Haskell County, Kansas, in February 1918, and that the infection had spread to American troops at Camp Funston in that state by March 4. The disease spread rapidly—with more than 29,000 cases in the army camps alone by September 27. Public health officials of many agencies, including the war and navy departments and the Red Cross, conferred about the alarming conditions and attempted to implement measures to combat the influenza’s spread, but the outbreak traveled along with the increased movement of people, especially soldiers in training camps and deploying to Europe. In early October, three “Leaksville boys in army service” at military camps in Louisiana, Seattle, and Boston—Robert Martin, Will Hodges, and Frank Rainey—were among the victims of the influenza. The first case reported in North Carolina was in Wilmington, where a 29-year-old father of two became the state’s first recorded victim. The port city was so hard hit, with 500 additional cases in a week, that local leaders set up a special hospital for influenza patients by the end of September. In the coming weeks, the disease quickly spread west across the state, especially along railroad lines. Governor Thomas Bickett issued a call for North Carolinians to stay home and protect themselves. In early October, Raleigh was said to be in the “grip” of influenza, with 50 girls at St. Mary’s School, 75 boys at the A & E College, and another 125 people across the city and Wake County infected. Mill villages were hard hit with infection. By mid-October, Rockingham County residents heard that the influenza was “on a rampage” in Roxboro, two counties east. There, thirteen funerals were held on one Wednesday alone and 600 more influenza cases were “without medical attention.” “It is said,” the Reidsville newspaper reported, “there are not enough well men to shroud the dead.” Local folks also heard of the death of the young president of the University of North Carolina, Edward Kidder Graham, who lost his life to the virus on October 26.

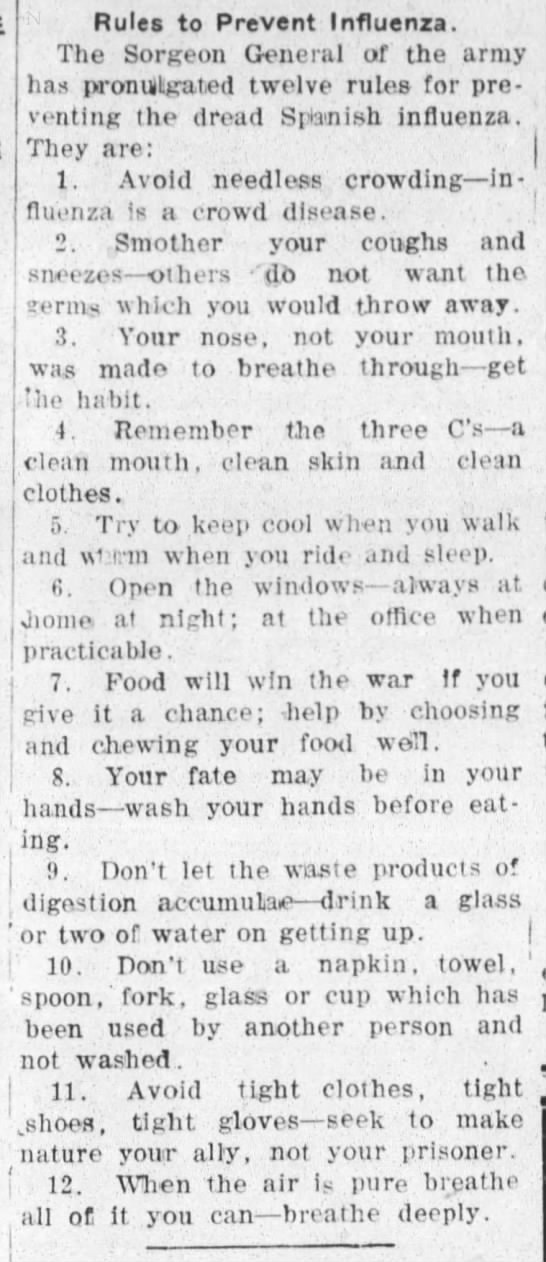

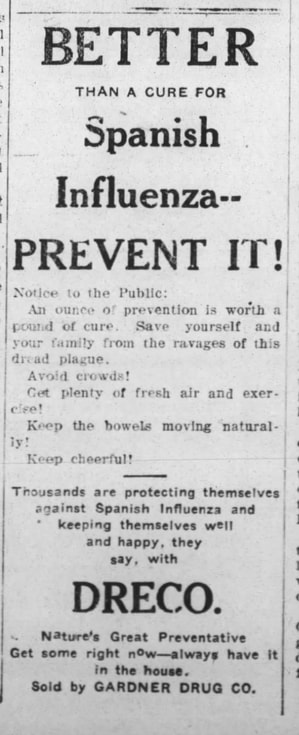

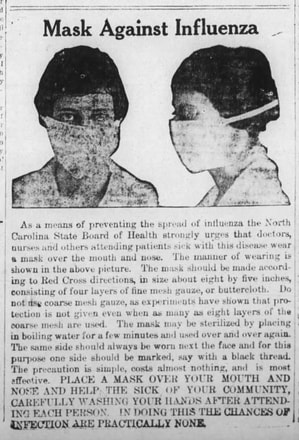

Local officials acted quickly. To prevent the spread of the deadly virus, a general shutdown of the city of Reidsville was ordered on October 7. The health ordinance closed all schools, churches, and theaters, and prohibited public gatherings of all kinds. Violators were to be fined $100 for each infraction of the ordinance. An emergency hospital was opened in the Lawsonville Avenue School building to take care of influenza patients. Mr. Francis Womack, Red Cross chairman, issued a call for additional nurses to staff the hospital. “It is gratifying that some have so nobly responded,” he said. “But we want more to volunteer for this noble work.” When the influenza situation seemed to improve by the end of the month, the emergency hospital was closed. Medical professionals offered guidance. The Surgeon General of the Army advised, “Avoid needless crowding—influenza is a crowd disease.” He also suggested opening windows, keeping cool, and washing hands. The North Carolina State Board of Health published instructions for making and using masks when attending the sick. The masks, according to Red Cross instructions, were to be eight by five inches and made of four layers of gauze. To sanitize them, masks could be placed “in boiling water for a few minutes and used over and over again.” Citizens were urged, “Place a mask over your mouth and nose and help the sick of your community.” Numerous advertisements began to appear in newspapers promoting the use of various tonics and treatments for the influenza and pneumonia spreading in the region. Some ads were designed deceptively in formats that appeared to be news articles. Some were remedies that had been available for decades.

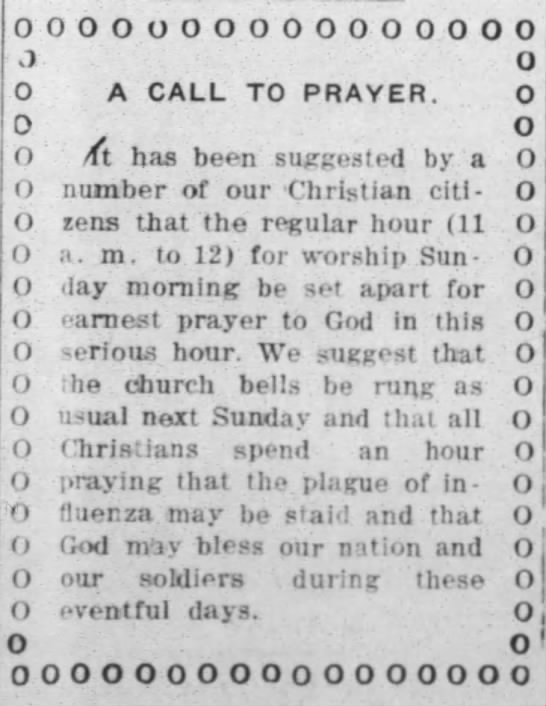

More Advertisements from 1918To reduce the epidemic’s impact, public activities were curtailed in October 1918. Long-planned community fairs in Bethany and Reidsville were postponed. Political meetings, including Governor Thomas Bickett’s speech in the New Bethel community, had to be cancelled. Still citizens were urged to vote in the upcoming November election. As long as crowds did not congregate at polling places, “There is no reason why any voter who is able to be outdoors should fail to exercise the right of franchise because of fear of this disease,” health officials assured the public. Churches also had to adapt during the influenza crisis. Some churches made requests for donations and tithes of their members during the shutdown. “Our church has been closed for several weeks on account of influenza,” the leaders of St. Thomas Episcopal Church wrote, but “our expenses are necessarily going on.” They asked the congregation to bring or send their dues to the church during a designated hour when the treasurer would be waiting there. When Reidsville houses of worship were closed by the town health directives, one minister was reported to have gone a bit outside the town to preach at a church in Wentworth one Sunday morning.

Boy Scouts rang the bell at the Reidsville First Presbyterian Church each night for a week in November to remind citizens to pray for the soldiers and for an end to the epidemic. Commerce was also affected. One observer noted, “The influenza epidemic has played smash with business in all sections of the State.” Even though several tobacco markets, including Winston-Salem, had already been closed, local pundits predicted on October 15, “No shutdown of the tobacco market, factories or stores are contemplated here.” However, to check the spread of the epidemic, state health authorities did request that tobacco warehouses close, which they did in Rockingham County on October 18. Tobacco warehouse managers worried that some of their competitors in the county would open before the lifting of the health ordinance. Having missed some important weeks in the tobacco trade, all were permitted to reopen on November 4, “the influenza epidemic having improved to such an extent that it was deemed safe to resume the sales.” The epidemic also brought disruption to local schools. Young teachers who had been working away in Jackson Springs and Gastonia returned home to Rockingham County in mid-October, their schools having closed “until the influenza epidemic is over.” The rural Bethany School was closed for two weeks but reopened by October 29. Schools in Reidsville were closed by the October 7 ordinance and reopened on November 11. Doctors assured families that it would be safe to return then and urged parents not to keep their children away from their classes. During the month of October 1918, at least 5,000 in North Carolina died from influenza and the pneumonia that often followed, with 55 of these victims being in Rockingham County. The first “crest of the epidemic was apparently reached during the fourth week of October,” the State Board of Health reported. The human toll was great. One of the local victims that week was 35-year-old Walter Ledbetter, “a well-known citizen of Madison,” who died after a “short illness with influenza,” leaving a wife and “five little children.” In early November, it seemed to many that the worst might be over locally. One Stoneville resident praised town officials for their careful leadership. “There have been only three cases of influenza within the corporate limits,” he said, and only “seven or eight in the community near here.” A young Wentworth woman home during the epidemic returned to her studies in Greensboro when the college reopened. The Reidsville library, which had been closed for six weeks, reopened in mid-November. Patients seemed to be recovering. The newspaper noted that Dr. W. A. Johnson of Monroeton was “out again after recovery from a hard spell of influenza and pneumonia.” It was reported that Miss May Hopper was now well and able to go back to school and that several others were “convalescing after an attack of influenza.” North Carolina Governor Thomas Bickett proclaimed a day of Thanksgiving for Sunday November 17, “rejoicing both for the victory that has attended American and allied arms and for the passing of the terrible epidemic.” However, outbreaks in various communities of Rockingham County flared again and continued into December. A McIver resident reported that “the influenza is again epidemic in his section.” Both black and white families were stricken. Manton Oliver, whose family operated the Reidsville newspaper, found himself “confined to his room with influenza” as it was declared that “the influenza situation continues bad here.” In the New Bethel township, there were “quite a number of influenza cases.” Mr. T. Z. Sparks of the Oregon section told the newspaper that “nearly all of his family have been down with the influenza.” A citizen of the Mt. Carmel area reported that the influenza epidemic continued to “rage” in that community, saying “The influenza is taking a new start in this section and we fear it will yet get in the schools.” By Thanksgiving 1918, over 80,000 Americans had died from the epidemic and news of deaths locally was frequent in this second wave of infection. Among the victims was 27-year-old Edna Johnston of Reidsville, who died of influenza-pneumonia only weeks after her brother Jamie had died from the same malady. Alvis Daniel Millner, age 51, died from influenza on December 4 after being ill for only two days. Mrs. Irvin T. Hinton and her four-year-old son Earle died during the first week of December and were buried the same day. Five others in the Hinton home also had influenza-pneumonia. On November 27, acting on the “advice of the city health officer and other physicians,” Reidsville again adopted an ordinance closing schools, the public library and churches. While in effect, the ordinance made it unlawful to operate “any motion picture or vaudeville show” or to hold any public meetings or gatherings. As with the earlier ordinance, all homes where influenza victims had died or had been nursed back to recovery had to be disinfected according to directions from the county health officer. This time, though, the fine for violating any of the directives was $50, half of the fine imposed two months earlier. During the second shutdown, the county school superintendent assured parents and children that the “time lost on account of the influenza will be made up during the spring term and that grades will be promoted.” High school teachers promised to give the senior class an extra month to complete all work required for graduation. The week before Christmas, Madison High School announced that its principal, J. C. Lassiter, had influenza and that the school would close again and not reopen until after the holidays.

The span from September through December was certainly a time of great concern for Rockingham County and all of the state. Besides the trauma of influenza deaths, many local families were hoping to hear that their soldiers were returning home from the war, but instead often received sad news that their loved ones were injured or missing in action. Other serious health concerns were present in the county as well in the fall of 1918. Two dozen Rockingham County patients were quarantined with diphtheria, in addition to 37 with typhoid and 14 with smallpox.

By the new year, the influenza epidemic seemed to be waning. The renovated Grande Theatre in Reidsville announced that it was properly ventilated and reopening in compliance with health ordinances. Students were back in school and in Reidsville were attending classes a half day on Saturdays in January to make up for lost instruction. Still, national health officials warned that the public should learn from the “bitter experience” of the epidemic, to “realize the seriousness of the danger,” and to expect “a large number of scattered cases” in the coming months. Emphasizing the ongoing concern about infection, one business reminded the public repeatedly in its January 1919 ads, “Our store is disinfected daily against spread of disease.” As the new year began, one Ruffin resident wrote that folks in his area were very thankful that all but one of the soldiers from their community had returned safely from the war and that the “flu situation in our town is greatly improved.” “Many homes are in mourning,” the editor of the Reidsville paper wrote. “We have had to mourn in common with other localities the loss of some of our brightest young men who have made the supreme sacrifices of war, as well as men and women who succumbed to the ravages of the influenza epidemic.” The year 1918, he concluded, had brought “strange, startling, and unprecedented” times. Sources: Western North Carolina Historical Association, “1918 vs. 2020: Epidemics Then and Now in NC,” Online Exhibit, https://www.wnchistory.org/virtual-exhibits/influenza/; John M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History (New York: Viking Penguin Group, Inc., 2004), 92-97, 338, and 355-356; Kip Tabb, “Historic Outbreak: Spanish Flu on NC Coast,” North Carolina HealthNews,https://www.northcarolinahealthnews.org/2020/05/02/historicoutbreak-spanish-influenza-on-nc-coast/ ; Going Viral: Impact and Implications of the 1918 Flu Pandemic, Online Exhibit, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Wilson Library, https://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/exhibits/show/going-viral/goingviral; Steve Case and Lisa Gregory, “Influenza Outbreak of 1918-1919,” NCpedia, Government and Heritage Library, State Library of North Carolina, https://www.ncpedia.org/history/health/influenza; William S. Joyner, “Infectious Diseases,” NCpedia, Government and Heritage Library, State Library of North Carolina, https://www.ncpedia.org/infectious-diseases part-ii . Articles in the Reidsville (NC) Review: “Spanish Influenza Prevalent,” September 27, 1918, 1; “Raleigh in Grip of Spanish Influenza,” October 1, 1918, 1; “Rules To Prevent Influenza,” October 22, 1918, 5; “A Call to Prayer,” October 25, 1918, 1; “Route 6,” November 26, 1918, 4; “Health Ordinance,” December 3, 1918, 6; and December 6, 1918, 7; “University President Dead,” October 29, 1918, 1; “Thomas S. Beall Dead,” October 8, 1918, 1; “Emergency Hospital Opens in Reidsville,” October 25, 1918, 1; “Spanish Influenza—New Name for Old Familiar Disease,” October 25, 1918, 6; “Editorial Column,” October 15, 1918, 4; “Stoneville,” November 5, 1918, 3; “Influenza Should Not Stop Voting,” November 5, 1918, 3; “Bethany,” October 29, 1918, 4; “Schools Will Make Up Lost Time,” December 3, 1918, 1; “Tobacco Warehouses To Open November 4,” October 29, 1918, 1; “Mt. Carmel,” November 22, 1818, 5; and December 13, 1918, 4; “A Call to the Good Samaritans,” December 6, 1918, 8; “U.S. Health Service Issues Warning,” December 13, 1918, 6; “Notice,” November 1, 1918, 8; “Should Be Forced To Close,” October 22, 1918, 4; “1918-1919,” December 31, 1918, 4; “Ruffin,” January 3, 1919, 5; “County Quarantine Officer’s Report,” October 8, 1918, 7; November 12, 1918, 1; and December 6, 1918, 2; “Some Timely Advice to the Influenza Convalescents,” December 2, 1918, 6; “Madison High School,” December 17, 1918, 1; “In Memoriam,” December 17, 1918, 4; “News of Reidsville and Rockingham,” November 26, 1918, 5; “Review of the Town and County News,” October 4, 1918, 8; October 8, 1918, 8; October 11, 1918, 8; October 15, 1918, 8; October 18, 1918, 8; October 29, 1918, 8; November 1, 1918, 8; November 5, 1918, 8; November 8, 1918, 8; November 12, 1918, 8; November 15, 1918, 8;November 26, 1918, 8; November 29, 1918, 8; December 3, 1918, 8; December 6, 1918, 8; December 13, 1918, 4; December 17, 1918, 8; December 31, 1918, 8; January 14, 1919, 8; “City Local News in a Condensed Form,” November 15, 1918, 5; November 29, 1918,1; December 3, 1918, 1; December 6, 1918, 1; December 13, 1918, 1; December 20, 1918, 1; December 31, 1918, 5; Advertisements in the Reidsville (NC) Review: Rockingham County Fair, September 20, 1918, 2; Mask Against Influenza, November 5, 1918, 5; Hill’s Bromide Cascara Quinine, November 8, 1918, 2; November 15, 1918, 4; November 22, 1918, 6; and November 29, 1918, 6; Foley’s Honey and Tar, November 22, 1918, 4; and November 29, 1918, 8; Dreco, November 5, 1918, 7; How To Use Vick’s VapoRub in Treating Spanish Influenza, October 18, 1918, 2; Druggists!! Please Note Vick’s VapoRub Oversold Due to Present Epidemic, Vick Chemical Company, October 29, 1918, 6; Vick’s VapoRub, November 8, 1918, 7; Peruna, October 29, 1918, 2; S. S. Harris, Clothier, December 24, 1918, 4; A. S. Price & Co., December 3, 1918, 8; January 3, 1919, 3. Reidsville Review accessed through NCLive, nclive.org, Historic North Carolina Digital Newspaper Collection, https://newscomnc.newspapers.com/ . To compliment May's This Month in History article, below is a virtual gallery of art created by Rockingham County High School's Advanced Visual Arts students, from Freshman to Senior. Their original works depict both the positive and negative impacts of COVID-19 on the class of 2020. MARC would like to thank not only the students for their creative and expressive artwork but their visual arts teacher, Leigh Cross, for making them available for the enjoyment of our online audience. We hope everyone enjoys them as much as we do! Foreword by Matthew Titchiner (MARC collection item 2013.50: 19th c. Whitall Tatum dry medical battery encased in wooden box) (MARC collection item 2013.50: 19th c. Whitall Tatum dry medical battery encased in wooden box) One of MARC's more mysterious collection items is our curious boxed device (pictured) that is actually a very well preserved example of an early dry medical battery. Produced by the Whitall Tatum Company in Millville, NJ, primarily a glass company, the item reveals a fascinating insight into a time where medical professionalisation, the dawn of electricity, the mail order catalogue and quackery all coalesced. Our single cell No. 1 Reliance model was an early version of one of many home-use electrotherapy devices, advertised as a 'cure-all' and raging in size from a book to a suitcase.  (MARC collection item 2013.50: inner workings of No. 1 Reliance model dry battery cell) (MARC collection item 2013.50: inner workings of No. 1 Reliance model dry battery cell) How it worked - the metal cup would be filled with an acid such as vinegar or lemon juice. One electrode made of copper and one of another metal such as aluminium would be connected to wires. Those wires would in turn be connected to two silver tubes. This would make the battery. In a time where electricity was a new and exciting discovery, shifting from the traveling shows of the early 19th century to the homes of the consumer, it is easy to see how a gullible and trusting public could be duped into electricity's magical properties, especially when receiving a 'revitalising' shock from one of these medical batteries. You can read more about this curious time in U.S. history from the article excerpt below (Wexler, A., 2017: The Medical Battery in United States (1870-1920): Electrotherapy at Home and in the Clinic: pp. 166 - 192)

In the 1920’s, Spray Cotton Mills brought Otto Kirches, a German violinist, to give violin lessons to the children of mill employees. Instead of insisting on a strictly classical approach, he encouraged the students to continue to play their regional tunes. Even adults came to Kirches for lessons and advice. As a result, many local fiddlers, notably Lonnie Austin and Charlie LaPrade, displayed much better technique than was usual in country fiddlers.

Although this music is often mistakenly called “mountain music,” Rockingham County has been home to many musicians who have made substantial contributions to American music in the fields of folk, old-time music, bluegrass and other forms of traditional music. Their names are usually not known to the general public, but they are held in high esteem by musicians, not only in America but abroad. In the 1920’s, banjo player and singer Charlie Poole took his band to New York and recorded “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down” and “May I Sleep in Your Barn Tonight, Mister?” This record sold 100,000 copies at a time when 5,000 copies was a hit, and 10,000 copies was giant smash. No classical, jazz, Broadway, or popular artist came close to that. Because of Charlie’s success, many musicians came to the area to work in the mills and to play music. Our county became a center for not only traditional country music, but for ragtime, early jazz and Tin Pan Alley tunes. A partial list of some early musicians based in and around Rockingham County in the 1920's and 1930's includes: Charlie Poole, banjoist and singer; Norman Woodlief, guitarist; Posey Rorer, fiddler; Lonnie Austin, fiddler and pianist; Tyler Meeks, guitarist; Hamon Newman, tenor banjoist; Earl Shirkey, ukulele player and yodeler; Lucy Terry, pianist; Red Patterson, banjoist and singer; Percy Setliff, fiddler; Buster Carter, banjoist; and Preston Young, guitarist and singer. In more recent times, banjo player Posey Roach (Eden) played with Flynn Rigney and the Virginia Partners; Alan Shelton was an influential banjo player with Jim Eanes and Jim and Jesse McReynolds, and he was a model for many banjo players all over the country. Gene Meade (Eden) set the mold for backing up fiddlers with his driving, spectacular guitar styles. (A recently released DVD of the Gene’s appearance at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival has hundreds of young guitarists trying to emulate his style.) Ruffin native Tim Austin was the founder of the Lonesome River Band and for years ran Doobie Shea Studios, a highly acclaimed recording venue. Kinney Rorrer, a native of Eden and grandnephew of Charlie Poole and Posey Rorer (*), is noted as a player and singer of Charlie’s songs. He is the author of Ramblin’ Blues the Life and Songs of Charlie Poole, a biography of Charlie Poole. Kinney hosts Back to the Blue Ridge, a radio program on the Roanoke, VA National Public Radio station, 89.1 FM WVTF, airing Saturdays from 8-10 pm and Sundays from 2 to 4 pm. (* note the difference in spelling) Doug Rorrer, Kinney’s brother, has been praised for his singing and his guitar work that echoes Gene Meade and Doc Watson. He has performed not only in the US, but in England, Scotland, and Italy. Doug owned and operated Flyin’ Cloud Studios and has produced many highly praised CD’s of old-time, bluegrass, and folk music. Doug’s son, Taylor Rorrer, performs professionally, sometimes with Doug and sometimes with other bands. Taylor is widely praised for his work on both guitar and fiddle. Ivy Sheppard (Bethany) of the highly praised South Carolina Broadcasters (who now live in Mount Airy), is well-known for her authentic fiddling and banjo playing as well as for hosting several radio shows featuring old-time and early bluegrass music. Dr. Don Wright, a dentist in Eden, is a fine banjo player, and has performed and recorded with musicians of the highest skill levels. He also plays guitar and banjo. Jesse Smathers of Eden is now the mandolin player/tenor and lead singer with the Lonesome River Band, having previously played with the James King Band and Nothing Fancy. His father Dave Smathers, played for many years with the Campus Tradition, an RCC based band. The family musical tradition dates back through several generations. The late Pat Smith from the Bethany/Monroeton areas kept old-time and bluegrass alive here for many years, playing every instrument in the band, although being best known for his fiddling and banjo playing. Pat’s sons, Terry and Billy, both continue to work in bluegrass. Terry played bass and sang with the Osborne brothers, and is currently with the highly praised band, The Grascals. Billy is a songwriter. His first cassette had 12 songs, every one of which was recorded by a bluegrass or country artist, an almost unheard-of feat. The Moore family from Ruffin has always played not only in family gatherings, but Jason Moore played bass with Mountain Heart and is currently working with the band Sideline. His brother, Darrin is an expert on the music of the Carter Family and plays and sings their music with great skill and authority. He is also an excellent bass player. Hubert Lawson and his family band, The Bluegrass Country Boys, are fixtures in the Piedmont NC area bluegrass scene. Mandolin and guitar player Ronald Pinnix, as far as can be determined, was the first person to record a flatpick guitar solo in a bluegrass recording. His creative playing influenced many local players. There is no way to verify the number of Rockingham County musicians who play regularly in living rooms and kitchens, on porches, in community centers and churches, and at area festivals. You may receive no public recognition, but you keep the tradition of “our” music alive. It is MARC’s hope that you (and your friends) will join us at Pickin’ at the MARC on November 9. It will be a time to share the love of the music, to meet and enjoy the talents of other musicians, and to jam with new friends. In doing so, you will help to solidify the foundation of Rockingham County’s musical tradition. |

Articles

All

AuthorsMr. History Author: Bob Carter, County Historian |

||||||||||||||

|

Rockingham County Historical Society Museum & Archives

1086 NC Hwy 65, Reidsville, NC 27320 P.O. Box 84, Wentworth, NC 27375 [email protected] 336-634-4949 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed