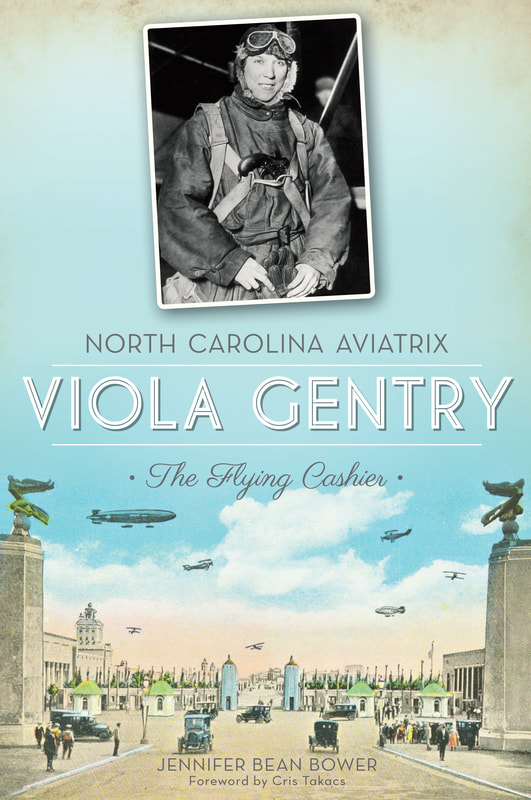

Viola Gentry of Rockingham County: America's "Flying Cashier" - Guest Article By Jennifer Bower12/15/2022 Foreword: Jennifer Bean Bower is an award-winning writer, native Tar Heel, and graduate of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and Wilmington. Bower is the author of North Carolina Aviatrix Viola Gentry: The Flying Cashier; Animal Adventures in North Carolina; Winston & Salem: Tales of Murder, Mystery and Mayhem; and Moravians in North Carolina. She lives in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, with her husband Larry and their pet rabbit Isabelle - and has been kind enough to write an article for MARC on Viola Gentry of Rockingham County. Viola Estelle Gentry was born in Rockingham County, North Carolina, on June 13, 1894, to Samuel and Nettie Walters Gentry. At the age of five, she and her younger sister Thelma were overcome by grief when their mother died. Several years later, the girls were saddened once again when Samuel moved the family to Danville, Virginia, and married Maydie Blanche Price. In Virginia, Viola endured a strained relationship with her stepmother and a monotonous job at a cigar factory. At the age of sixteen—in an effort to break free from the two—she ran away from home and attempted to join a circus in Greensboro, North Carolina. When that plan failed, Viola eloped with her boyfriend George Henry Gee. Soon after, likely at the behest of their parents, the marriage was dissolved and Viola was sent to live with an aunt and uncle in Jacksonville, Florida. The exact reason Viola was sent to Florida is unknown but it may have been to keep her separated from George, or to satisfy her cravings for adventure. Whatever the purpose, the journey to Florida was fortuitous as it was there she took her first flight. Unfortunately, Viola failed to ask her aunt and uncle for permission to take that flight and received a “sound spanking” when she landed. The flight, as well as the consequence of taking it, was an experience she never forgot. Following her daring jaunt through the clouds, Viola returned to Danville; but, she did not remain there long. In 1912, she was placed in the care of family friends—Mr. and Mrs. John Sears—who lived in Connecticut. The relationship between Viola and the couple was cordial and she credited them with providing her a good education. During the First World War, Viola supported the war effort by selling Liberty Bonds and working in an ordnance factory. When the war was over, she said good-bye to Mr. and Mrs. Sears; volunteered with the American Red Cross; traveled to San Francisco, California; secured a job as a switchboard operator; rented an apartment; and witnessed the event that changed her life. On a fateful day in July 1920, Viola watched in awe as Ormer L. Locklear, a Hollywood stunt pilot, landed his airplane on the roof of the tallest hotel in San Francisco. In one breathless moment, Viola’s destiny had been revealed. Her enthusiasm for aviation, an interest buried since her first flight in Florida, had been resurrected; and she would not let it be suppressed again. Viola declared that day—in that moment—that she would learn to fly. And, soon after, she did. Viola’s appetite for all things flight-related became insatiable. She attended lectures, read books, and saved money, to take her first flying lesson. When she finally had the amount needed, Viola arranged to meet a flight instructor at Crissy Field. However, her excitement to fly was dampened—albeit not extinguished—by the words of her male flight instructor who said “A woman should NOT fly, but should stay home, get married and raise a family.” Of course, Viola did not agree with those sentiments, so she packed her bags and headed to New York. She was convinced that the East Coast offered better opportunities for women interested in aviation and—at least in her regard—she was right. In 1924, while working two jobs, Viola learned to fly. The following year, she soloed; and in 1926, she flew underneath the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges. The stunt was front page news and Viola—who the press dubbed “the flying cashier” because of her position in a local restaurant—was an instant celebrity. Not everyone, however, was impressed with her aerial achievements. In fact, Viola’s parents felt her “activities were…unladylike” and that “she had disgraced the family.” Although Viola was likely disheartened by her family’s opinion, it did not stop her from flying. On December 20, 1928, she took off from New York’s Roosevelt Field in a Travel Air biplane and after “flying eight hours, six minutes, and thirty-seven seconds through winter weather,” Viola set the first officially recorded women’s solo endurance flight record. And, once again, her name, along with the story of her record-setting flight, was heralded in black and white.

Viola soared in the spotlight of an admiring nation and sought to achieve even greater feats. In 1929, she and John W. “Big Jack” Ashcraft endeavored to set a new refueling endurance flight record. The two intended to fly 174 hours or longer when they took off from Roosevelt Field on July 29, but fog and an empty fuel tank sent them to the ground. Ashcraft—who was at the controls—died instantly. Viola survived, but her injuries were so severe that she remained in a hospital for more than a year. Throughout her recovery and in the years that followed, Viola married—in secret because her fiancé’s family believed that women pilots were a disgrace to their gender—became a charter member of the Ninety-Nines; laundered clothes for Harold Gatty and Wiley Post when they flew around the world; supported women’s rights in aviation; presented lectures; and welcomed Amelia Earhart back to New York after her famous flight across the Atlantic. She competed in air races; helped preserve the history of early aviation; received numerous awards; and continued to fly until cataracts permanently grounded her in 1975. On June 23, 1988, at the age of ninety-four, Viola Estelle Gentry folded her wings. When she died, there were no large gatherings or grand speeches from famous men and women; yet, no words could have better defined her life than two sentences printed in the Danville Register & Bee. In her death notice, the author proclaimed that Viola “wanted to fly airplanes. And fly she did.” “And fly she did,” indeed.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Articles

All

AuthorsMr. History Author: Bob Carter, County Historian |

|

Rockingham County Historical Society Museum & Archives

1086 NC Hwy 65, Reidsville, NC 27320 P.O. Box 84, Wentworth, NC 27375 [email protected] 336-634-4949 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed