|

When I first encountered the Museum and Archives of Rockingham County (MARC) in my search for employment, I never imagined that they would take a chance on a newly minted green card holder (and a Brit at that!) for leadership. I certainly didn’t imagine this museum would grow such deep roots in my life, nor that the people would become like extended family in such a short span of time. But they did. The obvious qualities that attracted me to the MARC were its community participation, potential and people. Many museums boast interesting collections, historic architecture and varied programs, but not many can claim their existence as being truly grassroots or have such a compelling story. Born from the Rockingham County Historical Society (formed in 1954) with support from the Rockingham County government and many community members, the MARC emerged at the geographical and cultural center of the county. Stewarding a space that had been the site of county governance since 1787, two Revolutionary War sites and the painstakingly restored 1816 Wright Tavern that was brimming with tales left me hooked. It was also clear as the only county-wide museum in the area, MARC was uniquely placed to act as a positive galvanizing force, with the power to bring people together. But the real selling point for me was the passion of the Search Committee and staff who, during my interview, proudly told MARC’s story and vision for the future. When I received the call offering me the Executive Director position, I couldn’t say anything but “yes!” Shortly after starting my tenure as Executive Director at the end of 2019, which now seems a lifetime ago (or two), the world was brought to a halt by the COVID-19 pandemic. Shutdown came at a critical time when MARC needed to expand rapidly and diversify funding sources to keep operating. The pandemic was a challenge I certainly didn’t expect, and one that could have easily led to a possible closure within 6-8 months. Thanks greatly to Jeff Bullins, former MARC President, and the Board of Directors, we were able to secure multiple COVID-19 relief funds and a local grant from the Reidsville Area Foundation which enabled MARC not just to weather the storm but to pivot our events and projects to virtual formats. That was a difficult time and, in many ways, defined my tenure at the MARC, with added complexities at home as my wife and I juggled full-time work with many a sleepless night tending to the needs of our newborn twin daughters, far from extended family. Fletcher Waynick (former Operations and Facilities Manager) and Nadine Case (former Administrative and Volunteer Coordinator) were instrumental in keeping everything going at the museum during this period and I can’t thank them both enough! The team’s collective efforts allowed MARC to not only continue to deliver its mission but expand our online presence and install two new exhibits, The James P. Southern Korean War Exhibit and Heavy are the Scales: Griggs v. Duke Power Co. Exhibit. A rather unexpected result of the pandemic was that it left MARC with a new vision of what it could be and what it could do. One part of that vision was to realize the MARC’s full potential as a community convener. For the MARC to be able to draw together people from different areas and backgrounds and to acknowledge the full history of the people of Rockingham County. We have strengthened our relationships with the municipalities and rural areas of the county, and we have forged strong cooperative relationships with a wide variety of agencies and non-profit organizations in Rockingham County. MARC’s research and education regarding the Griggs v. Duke Power Co. case remains, for me, a personal highlight of our accomplishments and an example of our work to make connections. In 2019, when Valencia Abbott approached me about this 1971 United States Supreme Court case, it was a completely new history for me, and I spent hours researching all I could on the subject. Poignant but modest plans were set in motion to deliver the nation’s first permanent exhibit on the case, aiming to bring together the Duke Energy Foundation, the families of the 13 local African American plaintiffs and community leaders to celebrate this relatively unknown piece of local history that helped to secure workplace equity for all. Given the nature of the case, the volatile context for race relations during the 1960s and 1970s and the understandable reticence of the plaintiffs’ families to step forward, it was clear bringing these disparate groups together to share personal stories would be a significant challenge. But through championing our position as an apolitical cultural space that facilitates open dialogue, the project has grown beyond the state-recognized exhibit to include lesson plans, workshops, a North Carolina Historical Highway Marker, and North Carolina Civil Rights Trail Marker, with more ambitious plans in the works. Witnessing over 250 attendees at the Civil Rights Trail Marker event that included families of the plaintiffs from across the United States, County Commissioners, county tourism, Duke Energy, esteemed legal and cultural speakers and members of the community just visualized for me the power of MARC. Another large part of the vision that we set for MARC was the ability to be a more sustainable organization. I am proud that the MARC’s financial outlook is much improved, and we are continuing to make great strides in fiscal sustainability and transparency. It feels as though we have moved beyond fighting to keep MARC’s head above water, to now working to transform ourselves to engage, to inspire and to meet the needs of the communities we serve. Antiquated utilities were a large threat to the sustainability of our operations in the historic courthouse building. This was brought into sharp focus during the pandemic when parts of the system failed. During the early stages of fundraising for the project, another highlight of mine was receiving a letter from the U.S. Senate announcing MARC’s selection for a prestigious National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) grant, one of only 13 awardees in the nation. Seeing that gold seal embossed on the letter was quite surreal for me, at the time a green card holder who had only been in the United States for three years. It now proudly hangs on my wall. The top highlight for me, however, and what I will miss most are the people who are the heart and soul of the MARC. They not only adopted me but also my family. Offering a warm and generous welcome, throwing a baby shower for us, a leaving party and truly becoming a community “home away from home”, much to the reassurance of my close-knit U.K. family 3,000 miles away (who, incidentally, got to visit the MARC in March 2022). I’d like to take the opportunity to thank the Board, especially Jeff Bulins and David French for your leadership and advice, MARC’s staff for your dedication and support, as well as the hosts of volunteers behind the scenes, both past and present. The more I have gotten to know Rockingham County, from its deep industrial and agricultural histories to its rural charm, the more I have also found an uncanny similarity with my home village of Barrowford in County Lancashire, England. It is a friendly village where, like Rockingham County, the news travels fast, you’re not far from wide open fields and we enjoy our hearty comfort foods. Out of these similarities, if I may indulge in my love of history, I have found one thread in particular that links Rockingham County and Lancashire across the Atlantic - cotton. Although pre-Civil War cotton farming was largely found in South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, and in North Carolina confined to the Coastal Plains, cotton bales made their way to Rockingham County just as they did to Lancashire. The red-rose county of Lancashire had more than 2,600 mills at its zenith as the powerhouse of the British Empire’s cotton produced goods. When the American Civil War broke out, it affected the textile mills and its workers in both counties, known in the U.K. as the “cotton famine.” This shared history and hardship, from differing perspectives, lives on in the heritage of both communities to this day. I’d recommend the University of Exeter’s ‘Poetry of the Lancashire Cotton Famine’ if interested in the topic (https://cottonfaminepoetry.exeter.ac.uk/). So, whilst my time as part of the MARC staff is at an end and there is much I will miss, I am excited to see the MARC’s journey in the capable hands of its leadership team. I will, of course, continue to support MARC’s work any way I can as it has firmly secured a special place in my heart. And in the meantime, I am looking forward to taking what I have learned on to new challenges as Assistant Director of the Gaston County Museum, Dallas, NC (https://gastoncountymuseum.org). And I invite y’all to pop in to say hello!

0 Comments

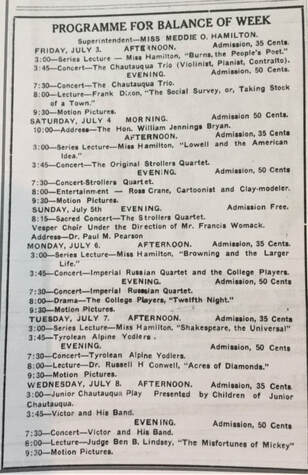

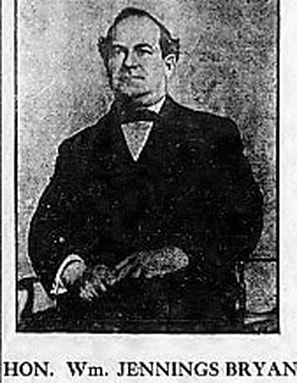

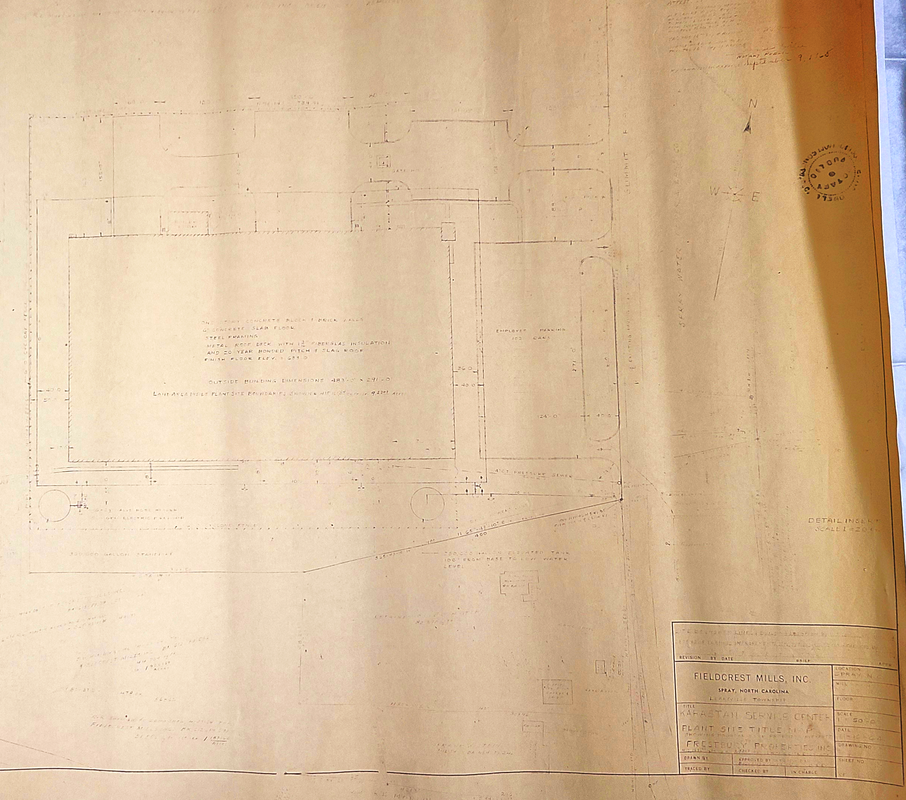

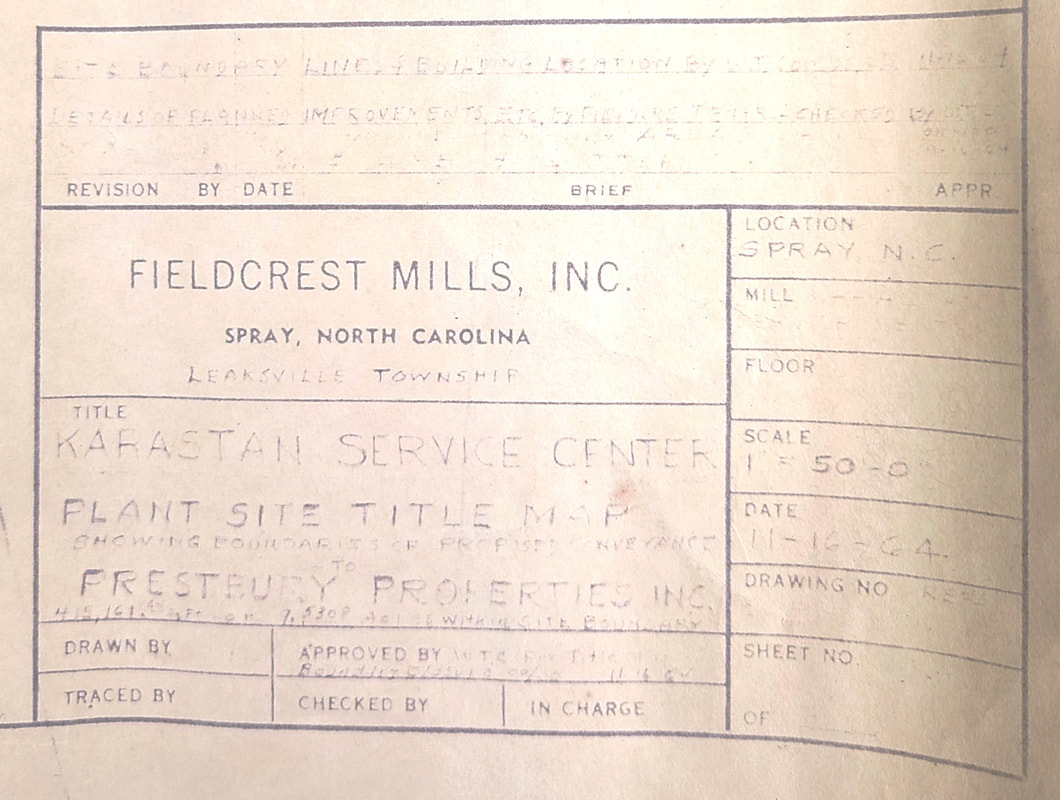

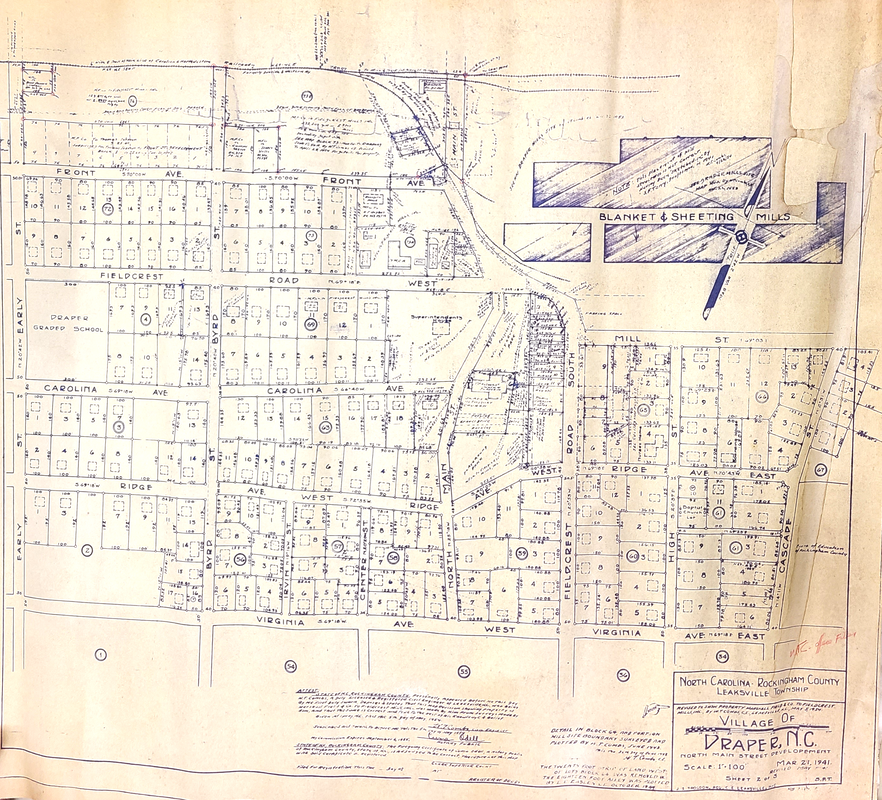

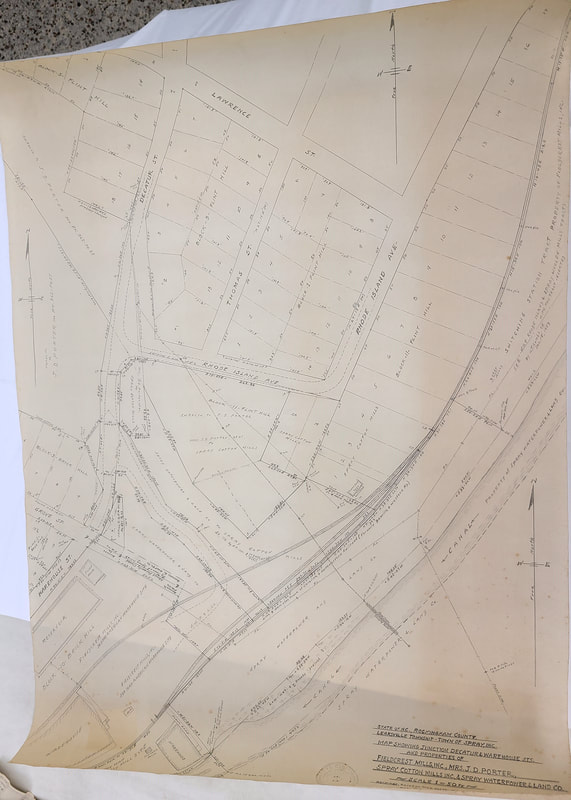

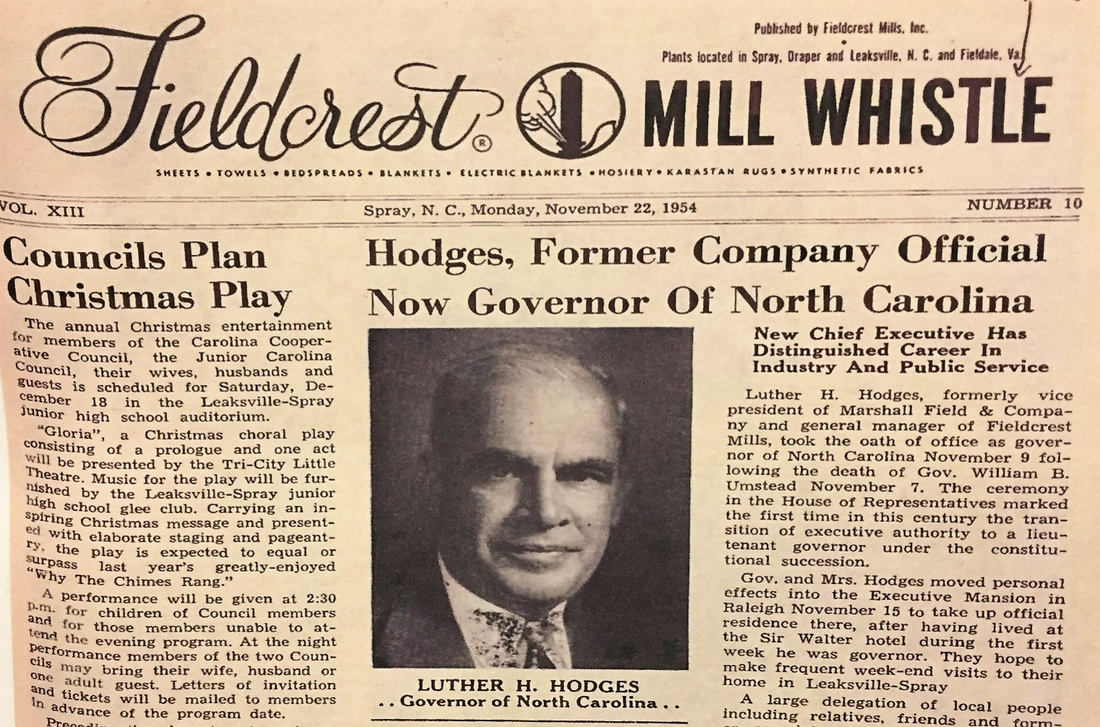

Mills heavily impacted the development of cities and towns throughout Rockingham County, and North Carolina more broadly. Historical maps allow some insight into the ways that these places looked throughout different points in time. Through historical maps, it is possible to learn about how interactions between the mills and the communities that were centered around them influenced one another and changed over time. John M. Morehead opened the Leaksville Cotton Mill in 1839.[1] It was one of the first textile mills opened in Rockingham County. In 1840, the Leaksville Cotton Mill employed 40 people, and by 1860, the census documented 80 women and 25 men working there.[2] Following the Civil War, Morehead would hire only white workers to work in his textile mill.[3] By 1890, there was a cotton mill in Reidsville, soon followed by Mayo Mills at Mayodan, the Spray Cotton Mill, and the mill at Avalon, which burned down in 1911, and was never reconstructed.[4] Benjamin Franklin Mebane would oversee the establishment of a number of additional mills in the late 1800s and early 1900s, including the Nantucket Mill, American Warehouse, and Lily Mill, among several others. Mebane had established so many mills that he did not have the money to fund all of them properly and Marshall Field and Company ended up taking control of his mills.[5] In the early 1900’s, one of the mills in Draper was owned by the German-American Co. in an area referred to as “the Meadows.” In 1912 the mill was purchased by the Marshall Field and Company, who also bought several of the mills in the surrounding area.[6] In 1953 Marshall Field and Company sold all of their mills in Rockingham County to Fieldcrest Mills, Inc.[7] Entire cities in Rockingham County were developed due to their proximity to a textile mill. The town of Draper is an example. Following the construction of the mill, the Rockingham Land Company sought to develop the town, a railroad was constructed, schools opened, churches were established, and the Bank of Draper was opened in 1920. Draper incorporated just under 50 years after the construction of the mill, in 1949.[8] The importance of the textile mills to the populace of Rockingham County historically cannot be overstated. The 1962 Hill’s Leaksville, Spray and Draper (Rockingham County, N.C.) City Directory refers to the mills as the “economic backbone of the Tri-Cities.”[9] Additionally, a 1977 report on the community by the County’s library reported that such a large percentage of the population of Rockingham County was employed in the textile industry that any economic downturn regarding textiles on a national level “would adversely affect Rockingham County’s entire economy.”[10] Evidence of the importance of mills to the county can be seen in many of the historical maps that are in the possession of the MARC. Of particular interest is a collection of several hundred maps that were originally owned by the Rockingham County government, which are largely maps made by engineers, for the purpose of delineating land ownership, rather than maps used for navigation or other purposes. Several of these maps include textile mill sites, including the Nantucket Mill site and the Spray Cotton Mill site, as well as several other non-mill properties owned by Fieldcrest Mills, Inc. These maps offer a unique glimpse into the past, which provide a visual framework for understanding the reach of the mills in various communities in Rockingham County, and the impact that textiles made in these local mills had on broader culture. One example of this is the map of the Karastan Service Center, owned, at the time, by Fieldcrest Mills, in Spray. The map dates from November 16, 1964. The Karastan Mill in Eden closed down operations in 2021, after 93 years of operation.[11] The Karastan Mill was a long term mainstay in Spray, and then Eden, outlasting many of the other mills in the area. Throughout its history, it was owned by Marshall Field & Co., Fieldcrest Mills, and Mohawk Industries. Karastan rugs are well known, and this mill shows how Eden has had a national influence. There are several other mills that are depicted in this map collection. With a slightly larger focus, another map is titled Junction of Decatur and Warehouse Streets and Properties of Fieldcrest Mills, Inc., Mrs. J.D. Porter, Spray Cotton Mills, Inc., and Spray Water Power and Land Co. Also owned by Fieldcrest Mills at times, this map was created in December of 1964. Spray Cotton Mills was originally a part of the Spray Water Power and Land Co., which was started by James Turner Morehead in 1889. Soon after the development of Spray Water Power and Land Co., James Turner Morehead shifted control of the company to B. Frank Mebane and W. R. Walker, who constructed the Spray Cotton Mills in 1896.[12] The following year, the Spray Cotton Mills were sold to Karl von Ruck, who is best known for studying and helping to create the tuberculosis vaccine.[13] The Spray Cotton Mills eventually closed down after 100 years in 2001. In January of 2023, a fire completely burned the main building in this complex. The mill was being sold or renovated for new uses when the fire broke out. [14] Both the map of Karastan Mills and Spray Cotton Mills are from 1964, just three years before Spray, Draper, and Leaksville merged to become Eden, a time of change for the community. The historical maps of Rockingham County depict important developments in communities and can provide important insights into the county’s textile mill history. Footnotes: [1] Hill’s Leaksville, Spray and Draper (Rockingham County, N.C.) City Directory (Richmond: Hill Directory Company, 1962), 17. [2] Lindley S. Butler, Rockingham County: A Brief History, (Raleigh: North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources Division of Archives and History, 1982), 42-43. [3] Butler, 58. [4] Butler, Rockingham County: A Brief History, 60, 66, 79. [5] Butler, Rockingham County: A Brief History, 79. [6] Hill’s Leaksville, Spray and Draper (Rockingham County, N.C.) City Directory, 18 [7] Butler, Rockingham County: A Brief History, 79. [8] Butler, Rockingham County: A Brief History, 72. [9] Hill’s Leaksville, Spray and Draper (Rockingham County, N.C.) City Directory, 18 [10] Rockingham County: The Library and the Community,” eds. Joyce Leeka, Deborah McCabe, and Deborah Russell, (Eden: Style-Kraft, 1977), 30. [11] Andrea Richards, “The End of the Wonder Rug,” New York Times, June 5, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/05/style/oriental-rugs-carpet-karastan-where-made.html. [12] Lindley S. Butler, “Spray Water Power and Land Company,” NCPedia, 2006. https://www.ncpedia.org/spray-water-power-and-land-company. [13] “Tuberculosis Vaccine Perfected in Asheville, 1912,” NC Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, November 5, 2016, https://www.ncdcr.gov/blog/2016/11/05/tuberculosis-vaccine-perfected-asheville-1912. [14] Susie C. Spear, “Sacred to Some, Only Ashes and Memories Remain After Spray Cotton Mills Fire,” Greensboro News and Record, January 27, 2023, https://greensboro.com/news/local/sacred-to-some-only-ashes-and-memories-remain-after-spray-cotton-mills-fire/article_d6e4911a-9dc5-11ed-96ec-47fa42a20e65.html Bibliography:

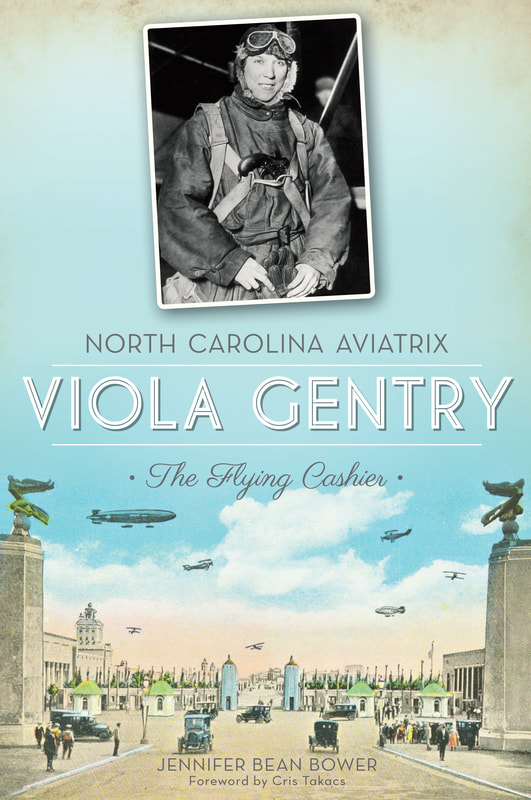

Butler, Lindley S. Rockingham County: A Brief History. Raleigh: North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources Division of Archives and History, 1982. Butler, Lindley S. “Spray Water Power and Land Company.” NCPedia. 2006. https://www.ncpedia.org/spray-water-power-and-land-company. Hill’s Leaksville, Spray and Draper (Rockingham County, N.C.) City Directory. Richmond: Hill Directory Company, 1962. Richards, Andrea. “The End of the Wonder Run.” New York Times, June 5, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/05/style/oriental-rugs-carpet-karastan-where-made.html. Rockingham County: The Library and the Community.” Eds. Joyce Leeka, Deborah McCabe, and Deborah Russell. Eden: Style-Kraft, 1977. Spear, Susie C. “Sacred to Some, Only Ashes and Memories Remain After Spray Cotton Mills Fire.” Greensboro News and Record, January 27, 2023, https://greensboro.com/news/local/sacred-to-some-only-ashes-and-memories-remain-after-spray-cotton-mills-fire/article_d6e4911a-9dc5-11ed-96ec-47fa42a20e65.html “Tuberculosis Vaccine Perfected in Asheville, 1912.” NC Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, November 5, 2016, https://www.ncdcr.gov/blog/2016/11/05/tuberculosis-vaccine-perfected-asheville-1912. Viola Gentry of Rockingham County: America's "Flying Cashier" - Guest Article By Jennifer Bower12/15/2022 Foreword: Jennifer Bean Bower is an award-winning writer, native Tar Heel, and graduate of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and Wilmington. Bower is the author of North Carolina Aviatrix Viola Gentry: The Flying Cashier; Animal Adventures in North Carolina; Winston & Salem: Tales of Murder, Mystery and Mayhem; and Moravians in North Carolina. She lives in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, with her husband Larry and their pet rabbit Isabelle - and has been kind enough to write an article for MARC on Viola Gentry of Rockingham County. Viola Estelle Gentry was born in Rockingham County, North Carolina, on June 13, 1894, to Samuel and Nettie Walters Gentry. At the age of five, she and her younger sister Thelma were overcome by grief when their mother died. Several years later, the girls were saddened once again when Samuel moved the family to Danville, Virginia, and married Maydie Blanche Price. In Virginia, Viola endured a strained relationship with her stepmother and a monotonous job at a cigar factory. At the age of sixteen—in an effort to break free from the two—she ran away from home and attempted to join a circus in Greensboro, North Carolina. When that plan failed, Viola eloped with her boyfriend George Henry Gee. Soon after, likely at the behest of their parents, the marriage was dissolved and Viola was sent to live with an aunt and uncle in Jacksonville, Florida. The exact reason Viola was sent to Florida is unknown but it may have been to keep her separated from George, or to satisfy her cravings for adventure. Whatever the purpose, the journey to Florida was fortuitous as it was there she took her first flight. Unfortunately, Viola failed to ask her aunt and uncle for permission to take that flight and received a “sound spanking” when she landed. The flight, as well as the consequence of taking it, was an experience she never forgot. Following her daring jaunt through the clouds, Viola returned to Danville; but, she did not remain there long. In 1912, she was placed in the care of family friends—Mr. and Mrs. John Sears—who lived in Connecticut. The relationship between Viola and the couple was cordial and she credited them with providing her a good education. During the First World War, Viola supported the war effort by selling Liberty Bonds and working in an ordnance factory. When the war was over, she said good-bye to Mr. and Mrs. Sears; volunteered with the American Red Cross; traveled to San Francisco, California; secured a job as a switchboard operator; rented an apartment; and witnessed the event that changed her life. On a fateful day in July 1920, Viola watched in awe as Ormer L. Locklear, a Hollywood stunt pilot, landed his airplane on the roof of the tallest hotel in San Francisco. In one breathless moment, Viola’s destiny had been revealed. Her enthusiasm for aviation, an interest buried since her first flight in Florida, had been resurrected; and she would not let it be suppressed again. Viola declared that day—in that moment—that she would learn to fly. And, soon after, she did. Viola’s appetite for all things flight-related became insatiable. She attended lectures, read books, and saved money, to take her first flying lesson. When she finally had the amount needed, Viola arranged to meet a flight instructor at Crissy Field. However, her excitement to fly was dampened—albeit not extinguished—by the words of her male flight instructor who said “A woman should NOT fly, but should stay home, get married and raise a family.” Of course, Viola did not agree with those sentiments, so she packed her bags and headed to New York. She was convinced that the East Coast offered better opportunities for women interested in aviation and—at least in her regard—she was right. In 1924, while working two jobs, Viola learned to fly. The following year, she soloed; and in 1926, she flew underneath the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges. The stunt was front page news and Viola—who the press dubbed “the flying cashier” because of her position in a local restaurant—was an instant celebrity. Not everyone, however, was impressed with her aerial achievements. In fact, Viola’s parents felt her “activities were…unladylike” and that “she had disgraced the family.” Although Viola was likely disheartened by her family’s opinion, it did not stop her from flying. On December 20, 1928, she took off from New York’s Roosevelt Field in a Travel Air biplane and after “flying eight hours, six minutes, and thirty-seven seconds through winter weather,” Viola set the first officially recorded women’s solo endurance flight record. And, once again, her name, along with the story of her record-setting flight, was heralded in black and white.

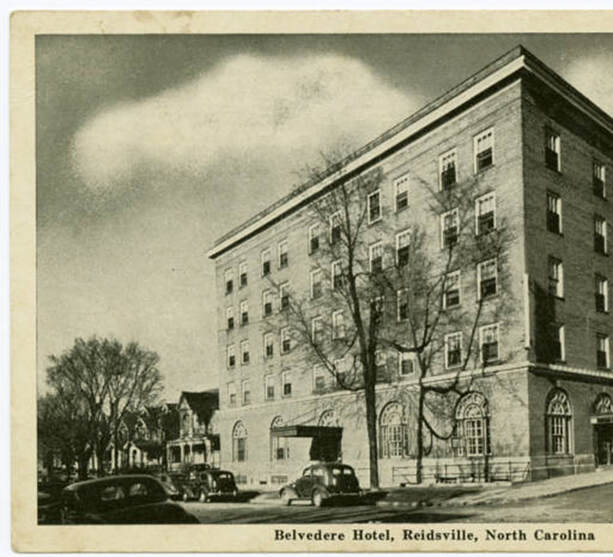

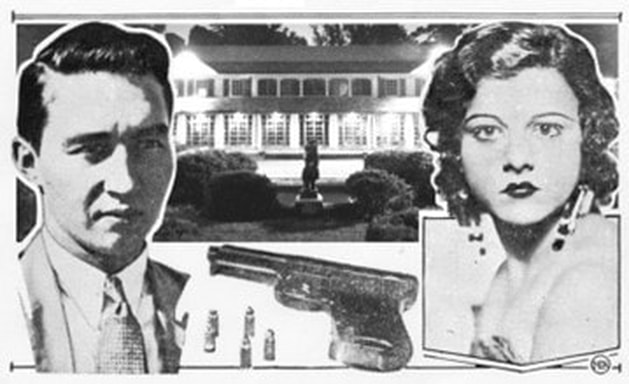

Viola soared in the spotlight of an admiring nation and sought to achieve even greater feats. In 1929, she and John W. “Big Jack” Ashcraft endeavored to set a new refueling endurance flight record. The two intended to fly 174 hours or longer when they took off from Roosevelt Field on July 29, but fog and an empty fuel tank sent them to the ground. Ashcraft—who was at the controls—died instantly. Viola survived, but her injuries were so severe that she remained in a hospital for more than a year. Throughout her recovery and in the years that followed, Viola married—in secret because her fiancé’s family believed that women pilots were a disgrace to their gender—became a charter member of the Ninety-Nines; laundered clothes for Harold Gatty and Wiley Post when they flew around the world; supported women’s rights in aviation; presented lectures; and welcomed Amelia Earhart back to New York after her famous flight across the Atlantic. She competed in air races; helped preserve the history of early aviation; received numerous awards; and continued to fly until cataracts permanently grounded her in 1975. On June 23, 1988, at the age of ninety-four, Viola Estelle Gentry folded her wings. When she died, there were no large gatherings or grand speeches from famous men and women; yet, no words could have better defined her life than two sentences printed in the Danville Register & Bee. In her death notice, the author proclaimed that Viola “wanted to fly airplanes. And fly she did.” “And fly she did,” indeed. August 1932In the summer of 1932, Rockingham County found itself involved in a sensational celebrity news story when accused murderer Libby Holman Reynolds turned herself in at the Rockingham County Courthouse. The Broadway starlet was in Wentworth for only about two hours on a fiercely hot August afternoon, but her presence and the circumstances surrounding the death of her millionaire husband meant that her surprise arrival in Reidsville the night before and the location of her surrender to authorities were mentioned in news articles all over the nation. In the early morning of July 6, 1932, Z. Smith Reynolds, 20-year-old heir to the R. J. Reynolds tobacco fortune, suffered a gunshot wound to the head at Reynolda House, the family mansion in Winston-Salem, and died about five hours later at NC Baptist Hospital. Was it suicide, an accident, or murder?  (Above: As a Broadway star, Libby Holman was known for her seductive appearance and singing voice. Image from Wikimedia Commons) (Above: As a Broadway star, Libby Holman was known for her seductive appearance and singing voice. Image from Wikimedia Commons) At first, the death was called a suicide. His widow, Libby Holman Reynolds, told officials that Smith had killed himself after a party on the grounds of the estate. The young millionaire had threatened suicide several times before, his wife said. Dr. Fred Hanes, hospital physician who attended the victim, officially deemed the death a suicide and most of the Reynolds family seemed to accept this determination. Local authorities investigating Reynolds’ death, however, saw many contradictory details in accounts of the party the evening before the shooting, the hours at the hospital, and the discovery of the gun. Both Libby and Smith’s friend Albert (Ab) Walker, age 19, came under suspicion, and Forsyth County Sheriff Transou Scott called for further inquiry. A private coroner’s inquest was held. A distraught Libby testified only that she saw Smith with the gun to his head and saw a flash but remembered nothing else about the shooting or the evening leading up to it. The more testimony officials gathered, the more muddled the evidence seemed. Where was the bullet? Why was the gun not seen the first three times the scene of the shooting was examined but was clearly lying on the edge of the rug near the door the fourth time investigators entered the sleeping porch where Smith Reynolds was shot? Although local officials had many lingering questions about the possible involvement of both Libby and Ab, neither was detained. The inquest jury vaguely stated their verdict that Reynolds had died “from a bullet wound inflicted by a party or parties unknown.” The Sheriff saw the death as unsolved and continued the investigation. During the last week of July, the grand jury was convened. On August 4, they indicted both the widow and the lifelong friend on charges of murdering the young millionaire, charging that the pair “did unlawfully, willingly, feloniously, and premeditatedly of malicious forethought, kill and murder one Z. Smith Reynolds.” Ab was picked up almost immediately and taken to the jail in Winston-Salem. Libby, however, had left North Carolina with her family and gone back to Ohio about three weeks earlier. When authorities looked for her there, she had disappeared. It was later revealed that Libby was able to elude law enforcement and the media by shuttling between homes along the Chesapeake Bay connected to her millionaire friend, Louisa Carpenter. A month after the shooting, on Wednesday, August 8, the 26-year-old widow, Libby Holman Reynolds, surrendered to the Rockingham County sheriff in Wentworth at the county courthouse (now the building housing the MARC). She and her lawyers apparently chose Wentworth thinking it might be out of the limelight. There the judge handling the case, A.M. Stack, was hearing cases for a week, and the setting in the quiet rural county seat of Wentworth would possibly allow Libby to briefly appear, obtain bail, and move back to her undisclosed hideaway. As for media coverage, Wentworth seemed like a good choice because it had “no railroad, no telegraph facilities and only one telephone line,” according to a Holman biographer. Even in a village courthouse, however, these legal proceedings were not likely to be out of the public eye. Not only did the case involve perhaps the wealthiest family in North Carolina, but Libby was also a celebrity in her own right, having appeared in successful Broadway shows to rave reviews. She had developed a significant following as a “husky-throated” Broadway singer of blues and torch songs in New York City. One admirer was Smith Reynolds, the youngest of the four children of tobacco company founder, R. J. Reynolds, Sr. Smith first saw Libby in a production in Baltimore and then pursued her on tour in the U.S. and on trips abroad with her theater friends. As an aviator who owned his own plane, Smith Reynolds was able to fly across the U.S. and to Europe in pursuit of the “raven-haired stage beauty.” Libby was Reynolds’ second wife, having married Smith only a short time after his divorce from Anne Cannon, and only seven months before his death.  (Above: Libby Holman in the courtroom of the Rockingham County Courthouse on August 8, 1932. Despite the intense heat of the day, she was covered from head to toe in a widow’s black outfit and veil, so opaque that many of the spectators were not certain that they had actually seen the famous Broadway star. Image from Wikimedia Commons) (Above: Libby Holman in the courtroom of the Rockingham County Courthouse on August 8, 1932. Despite the intense heat of the day, she was covered from head to toe in a widow’s black outfit and veil, so opaque that many of the spectators were not certain that they had actually seen the famous Broadway star. Image from Wikimedia Commons) Driven to North Carolina by Louisa Carpenter, the friend who had been helping her hide from the public, Libby arrived in Reidsville just hours before her court appearance and checked in at the Belvedere Hotel. She was met there by her brother and her father Alfred Holman, who was assisting in her legal defense. Around 2:30 on the afternoon of her surrender, Libby was driven the eight miles to the courthouse in Wentworth in a limousine. She waited before going into the courthouse a few yards across the road in the parlor of what is now Wright Tavern, when it was a hotel and the private home of Wentworth postmaster Numa Reid. There, the Rockingham County Sheriff Leonard M. Sheffield served the warrant for her arrest. Celebrity photographers, a newsreel crew, and scores of local spectators swarmed around the Rockingham County Courthouse that afternoon. An observer estimated those gathered there to number five hundred. One of those in the crowd that day was Wentworth teenager and future textile executive Dalton McMichael, who sold copies of the local newspaper, making a $10 profit. Women from a nearby church had their food items for sale just as they did for every court session, but with such a large crowd on a very hot day, sales were particularly brisk. Others sold drinks and food from wagons or stands on the grounds, while most just crowded around the red brick building to catch a glimpse of the glamorous singer, now embroiled in scandal. Reporting for the Reidsville Review, local journalist W.C. (Mutt) Burton wrote of the scene that the surrender of Libby Holman in Wentworth was “enough to keep a battalion of newspaper reporters in feverish action, all afternoon and far into the night.” Dressed all in black with her face heavily covered by a widow’s veil, Libby Holman moved quickly through a largely silent crowd and entered the courthouse, accompanied by her father and Reidsville physician Dr. M. P. Cummings. The physician was needed, because, as reporters had been told earlier by Mr. Holman, his daughter was pregnant with Smith Reynolds’ child. This fact and the shock of having lost her husband so tragically combined to make her health very fragile, he said.  (Above: The Belvedere Hotel in Reidsville, NC, circa 1915-1930. Libby Holman and a small entourage met there the evening before her appearance the next day before a judge at the Rockingham County Courthouse in Wentworth. Image from North Carolina Postcards, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill) (Above: The Belvedere Hotel in Reidsville, NC, circa 1915-1930. Libby Holman and a small entourage met there the evening before her appearance the next day before a judge at the Rockingham County Courthouse in Wentworth. Image from North Carolina Postcards, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill) The courtroom was extremely crowded. Libby appeared before the judge, but the prosecutors basically spoke of how weak their evidence was against her and agreed to $25,000 bail, the same as had been ordered for her co-defendant, Walker. One local attorney later ranted about the fact that the judge called Libby to the bench and allowed the accused murderer to sit at his desk and sign the required papers, a gesture the attorney considered totally inappropriate. As the singer and her entourage exited the building and drove back to Reidsville, reporters followed. After her appearance in Wentworth, Libby somehow was able to elude the reporters and photographers camped out back at the Belvedere Hotel overnight and slipped out around 2 a.m.--to an unknown destination. A November 1932 court date was set for the trial of Ab Walker and Libby Holman Reynolds, but after a letter from the Reynolds family saying that they would support such a move, all charges were dropped against the pair because of insufficient evidence. Over time, details about the circumstances surrounding the shooting of Z. Smith Reynolds continued to emerge and the public remained interested in the mystery of his death. Several accounts of an alcohol-fueled party in the hours leading up to the shooting became known. One biographer even claimed that, despite Prohibition laws still being in effect, a five-gallon keg of corn liquor bought from a local bootlegger was provided for the 11 party guests and that many in attendance, including Libby, were drinking heavily. Through research, biographers and journalists pieced together a narrative of events. Libby, Ab, and another house guest, Blanche Yurka, a theater friend of Libby’s, had brought Smith Reynolds to NC Baptist Hospital on the night of the shooting. Investigators were told that Ab had first called an ambulance, but because it had not yet arrived, he had pulled the unconscious Smith from the sleeping porch, across the gallery, and down the steps, aided by Libby and then Blanche. The three then drove to the hospital in Libby’s car, with Blanche in the back seat, cradling Smith’s head. Ab drove and Libby, wearing only a peach-colored negligee, sat in the front. Reportedly, a nurse later helped the distraught wife into a robe to cover herself while Libby, Ab, and Blanche waited on the fifth floor of the hospital. Around 1:10 a.m., Smith Reynolds had been brought into the hospital, where doctors determined that the young man, unconscious the entire time, was not going to make it. He died at 5:25 a.m. In another tie to Rockingham County, one of the first two physicians to examine Reynolds was 26-year-old intern, Dr. Alexander M. Cox, who moved to Madison the next year and practiced medicine there for four decades. Although he was not interviewed by authorities at the time of the shooting, Cox told a biographer of Libby Holman in the 1980s that, because of the location of the entry and exit wounds, he believed that Smith Reynolds had been shot from some distance away and that it was not, then, a suicide. Ninety years later, it is still not clear who shot Z. Smith Reynolds. Financial matters, however, were settled within months, with Libby and her son, Christopher, who was born in January 1933, receiving about seven million dollars from the Reynolds estate. Libby lived the rest of her life under a cloud of suspicion, but over time did return to performing and used much of her money to fund philanthropic causes. The day Libby Holman Reynolds surrendered in Wentworth was notable in local history for the headlines it generated across the nation. Noting that the crowd gathered at the courthouse was both interested and sympathetic, reporter Dick Wilson summed up that August afternoon as “quite a gala day in Rockingham County,” “touched with … sincere sadness.” Recordings of Libby Holman are readily available online. Listen to two of her signature tunes, “Moaning Low” and “Body and Soul,” on YouTube below:

References

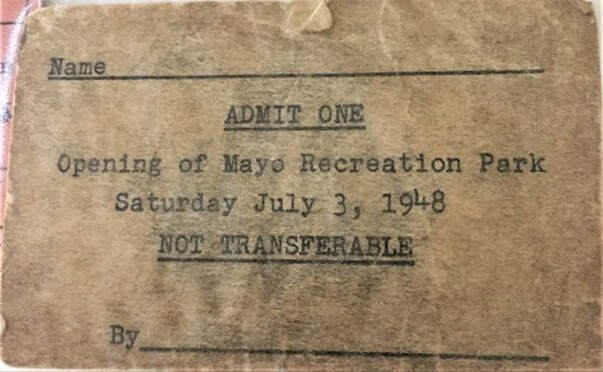

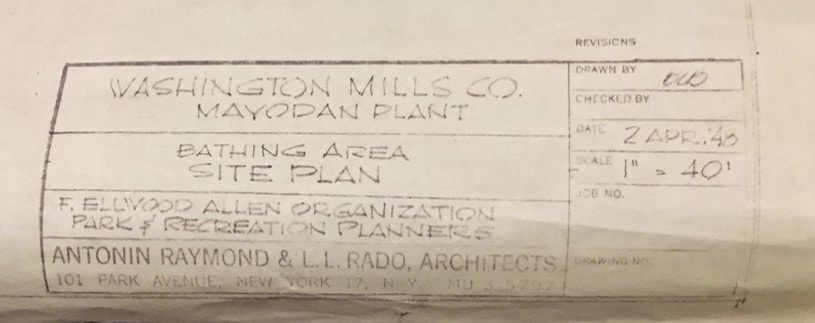

Jon Bradshaw, Dreams That Money Can Buy: The Tragic Life of Libby Holman (New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1985) Quoted from Bradshaw: shooting aftermath and hospital scenes, 117-123 (based on 309-page transcript of coroner’s inquest), coroner’s inquest and grand jury, 148, 156; Cox account, 152; Wentworth and media, 163; Hamilton Darby Perry, Libby Holman: Body and Soul (Boston and Toronto: Little, Brown and Company, 1983), in particular Chapters 22 and 23, 173-187; One of the causes funded by Libby Holman was Martin Luther King, Jr.’s trip to India in the late 1940s, where he studied the methods of Gandhi, nonviolence, and passive resistance. See also The Christopher Reynolds Foundation, Inc. https://creynolds.org/about-us/; “Image from Winston-Salem Journal, “Tragic Pairing of Tobacco Heir and Torch Singer,” Blog, North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, https://www.ncdcr.gov/blog/2014/11/29/tragic-pairing-of-tobacco-heir-and-torch-singer; Image of Belvedere Hotel, circa 1915-1930, North Carolina Postcards, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill, https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/nc_post/id/4425; Dick Wilson, “Libby Holman Creates Furor at Wentworth,” Leaksville News, August 11, 1932, 1 (“sincere sadness” quotation); Meredith Barkley, “On Call: Cox Lived To Doctor,” Greensboro (NC) News & Record, November 2, 1993, https://greensboro.com/on-call-cox-lived-to-doctor/article_34083080-dd54-5632-bbc0-5f3f330a31ed.html; Meredith Barkley, “Big Day: When Libby Holman Surrendered,” Greensboro (NC) News & Record, August 4, 1992, https://greensboro.com/big-day-when-libby-holman-surrendered/article_854969a9-765f-5536-89d8-ac2cad3f598d.html#:~:text=She%20finally%20surrendered%20in%20Wentworth,by%20two%20carloads%20of%20reporters; Articles from The Reidsville Review, Reidsville, NC: ”Smith Reynolds Kills Himself,” July 6, 1932, 6; “Youth’s Guardian Holds to Suicide Theory: Guardian Sure Reynolds Took His Own Life,” July 8, 1932, 1; “Smith Reynolds Inquiry Is Resumed Today: Seek Answer to the Question,” July 11, 1932, 1; “Will This State Get Reynolds Inheritance Tax,” July 11, 1932, 1; “Belvedere Is under New Management,” July 11, 1932, 1; “Smith Reynolds’ Widow Quits Winston-Salem,” July 13, 1932, 1; “Ann Cannon Is in Spotlight Again,” July 13, 1932, 1; “Jury Verdict in Reynolds Death Very Indecisive,” July 13, 1932, 1 (“raven-haired” quotation); “Sensations End Suddenly at the Twin-City,” July 15, 1932, 1; “Sheriff Scott Thinks Reynolds Was Slain: Is Convinced That It Was Not Case of Suicide,” July 18, 1932, 1; “The Reynolds Estate Still Is Unsettled,” July 22, 1932, 1; “Reynolds Case Has New Twist,” July 22, 1932, 1; “Holman Critical of Reynolds’ Case Probe: Sends Officers Telegram About Whole Affair,” July 25, 1932, 1; “Libby Holman Seeks To Settle Large Estate,” July 25, 1932, 1; “Libby Holman and Ab Walker Are Indicted: Walker Jailed, Seek Widow in Reynolds Case,” August 5, 1932, 1; “Holman Keeps Daughter Hid,” August 5, 1932, 1; “Libby Holman Coming to Wentworth,” August 8, 1932, 1; William Burton, “Libby Again Fades from the Public Gaze: Leaves Here with Brother and a Friend,” August 10, 1932, 1 (“feverish action” quotation); “Accused Torch Singer Has Been in Maryland,” August 10, 1932, 1; “Libby Reynolds Snapped at Wentworth Court,” August 12, 1932, 4; “Date for Trial Is Not Yet Fixed,” August 12, 1932, 4; “Now Facing Murder Indictments,” August 15, 1932, 1; “Has Enough Evidence To Convict?” August 22, 1932, 1; “Dick Reynolds Returns to Winston-Salem: May Talk about the Death of His Brother,” August 24, 1932, 1; “Thinks Brother Was Murdered,” August 26, 1932, 1; “Exhume Body of Young Smith Reynolds: Autopsy Was Performed on August 23rd,” September 2, 1932, 1; and “Libby’s Trial To Be Delayed,” September 21, 1932, 1. July 1948 (Above: Admission ticket for the dedication of Mayo Park in July 1948. Only those with these special tickets were allowed to attend the festivities. Courtesy Connie Fox, Scrapbook, ticket donated by Gloria Steele to the Mayo River State Park Archives) (Above: Admission ticket for the dedication of Mayo Park in July 1948. Only those with these special tickets were allowed to attend the festivities. Courtesy Connie Fox, Scrapbook, ticket donated by Gloria Steele to the Mayo River State Park Archives) In July 1948, the Washington Mills Company opened a new and exciting recreational facility for its employees and their families—Mayo Park, often called Mayo Lake by locals. Situated about two miles north of Mayodan, the park offered serene, wooded areas and trails, a large picnic pavilion, a playground, fishing, and the highlight of the facilities: a bathhouse, a sandy “beach,” and a lake for swimming and diving. Special invitations and admission tickets were required when a crowd estimated to number about three thousand gathered for the July 3, 1948, event dedicating the park. The President of Washington Mills, Agnew Bahnson, gave the keynote speech, explaining that the mill was partnering with the Mayodan Y.M.C.A. to provide “plenty of fresh air, sunshine, camping, family picnic areas, nature trails, games, swimming, and other forms of recreation” for the company’s employees, their relatives, and other citizens of the community, where the Mayodan mill had been located since the 1890s. Other officials of the company, including W.H. Bollin, General Manager of the Mayodan plant, and R. A. Spaugh, company vice-president, were present to show their support, as was Mayodan mayor A. G. Farris. In fact, the park opening was considered important enough to postpone the very popular Bi-State League baseball game originally scheduled for that day in Mayodan. Plans for the 400-acre park and facilities, a “company gift to the community,” were drawn up in the spring of 1948, and in only a matter of months, the park was ready for use. In addition to the speeches by dignitaries, the opening day’s celebration included a diving exhibition from the platform at the newly created lake, an afternoon of swimming, and a hearty barbecue lunch, deemed “the best free food he had ever gotten anywhere” by local photographer Pete Comer who was on hand with his camera to record the event. The main attractions at Mayo Lake for youngsters who grew up going there during the 1950s and 1960s were the summer swimming facilities. Use of the lake for swimming and diving required employee and family identification, YMCA membership cards, or other permits. Bus transportation from the Y in Mayodan to Mayo Lake, on a vehicle they called the “Gray Goose,” enabled many youths to come for swimming. When they checked in at the bathhouse, for a fee of ten cents, they were issued a metal basket to hold their street clothes and given a large number pin to wear on their swimsuits. By the mid-1950s, Mayo Park gradually became the meeting place for many area organizations. Sunday and Wednesday evening vespers were well attended and involved an array of local churches and choirs. Scouting events of all kinds were held at the park. Aquatic life-saving instruction for teenagers was offered at Mayo Lake, leading to certification by the Red Cross. Summer day camps were held, with different weeks for younger boys and girls, and each fall a “Science Camp,” taught by students and staff from UNC Greensboro, was organized for western Rockingham fifth graders. During its heyday, Mayo Park had a parking lot for 400 cars. Many employee gatherings were also held at the large pavilion.  (Above: The Pavilion at Mayo Park was featured on the cover of a Japanese architecture publication from the 1960s. Architecture, a Monthly Journal for Architects and Designers, April 1962, Archival collection of Mayo River State Park) (Above: The Pavilion at Mayo Park was featured on the cover of a Japanese architecture publication from the 1960s. Architecture, a Monthly Journal for Architects and Designers, April 1962, Archival collection of Mayo River State Park) One of the most significant aspects of the original Mayo Park was its architecture. Washington Mills contracted with the firm of Raymond and Rado in New York to plan the park. Its structures were designed by Antonin Raymond, an associate of renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Raymond, a Czech designer, had worked with Wright in Japan on several projects in the 1920s and 1930s and the designs of the Mayo Park structures reflect both Japanese lines and Wright’s influence. Raymond explained the importance of blending architecture with natural settings in his plans for the park: “The idea behind the design of the buildings was to keep …[them] in harmony with the surroundings, by using natural materials, unpainted and unvarnished.” The Pavilion at Mayo Park was built according to these standards. The columns and rafters were made of hickory, the main roof was covered with cedar shingles, and the huge pavilion fireplace was constructed of local stone. It is thought that the steep pitch of the pavilion’s roof prevented the serious decay that caused the original bathhouse to be demolished. Another popular attraction of the park was a T-33A aircraft donated for display by the U.S. Air Force in 1965. Over the time it was at Mayo Park, the aircraft was enjoyed by the public and carefully maintained. As Mayodan Town Manager Jerry Carlton reported to military officials in 1976, “Our children and grownups alike have spent many pleasurable hours examining the plane and they continue to enjoy making those imaginary flights.” The aircraft was exhibited on the park grounds until it was returned to the Marines at Cherry Point, NC, in 1979. In creating the recreational setting at Mayo Lake for its employees, Washington Mills was continuing the practice of employers engaging in the daily lives of their workers, not only on the job, but also outside the workplace. Textile mills such as those in Rockingham County set up company stores and provided housing for their labor force, as well as offering other organized services and activities for their employees. In the early 1900s, for example, Spray Cotton Mill opened a day nursery in its factory for workers’ young children. In Like a Family, a comprehensive look at the lives of Southern cotton mill village workers, historians noted an array of mill-sponsored activities beyond work hours that included exercise sessions, baseball teams, sewing and cooking classes, and even brass bands, such as the 1920s Mayo Mills Band. These structured recreational activities were especially prevalent in the early twentieth century, but by midcentury were generally becoming fewer in number. In a 1950s promotional publication, however, Washington Mills boasted of its many offerings for its workforce: “These People Make the Product and they enjoy themselves in their leisure hours in many and varied forms of recreational facilities provided them by Washington Mills.” The brochure included photographs of participants in bowling and ping pong at the YMCA located adjacent to the Mayodan mill, as well as scenes from the Mayodan baseball field on Main Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, and the pavilion and swimming facility at Mayo Park. After the swimming facilities were closed in the 1960s, community residents continued to meet at Mayo Park for picnics and other gatherings through the mid-1970s. The area afterward fell into disuse, however, and for about thirty years was closed to the public, until it became a part of the Mayo River State Park. In 2005, the state of North Carolina allocated more than a million dollars to preserve the park’s structures and hire staff. Historian Dr. Lindley S. Butler served as chairperson of the Mayo River State Park Committee and several other Rockingham County Historical Society members were also instrumental in the preservation of the original Mayo Park structures, including Bob Carter and Charlie Rodenbough. To many citizens of western Rockingham County, Mayo Park was a much appreciated recreational destination from its opening in 1948 through the 1970s. Connie Fox, of Mayodan, may have the longest association with the Mayo Park area. She has worked at the office of the Mayo River State Park since its opening, just steps from Mayo Lake and the site where the original Mayo Park bathhouse once stood. (The original home of the park caretaker is now the state park office.) In fact, Fox, whose mother worked in the personnel office of Washington Mills, began her many visits to Mayo Park at the age of eighteen months and has many fond memories of playing on the wooden swings at the playground there as a child. “It was the best thing that ever happened to Mayodan,” she said. References

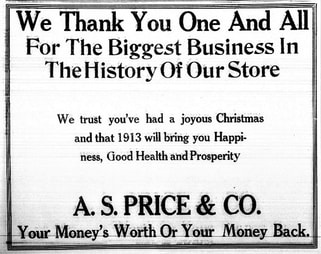

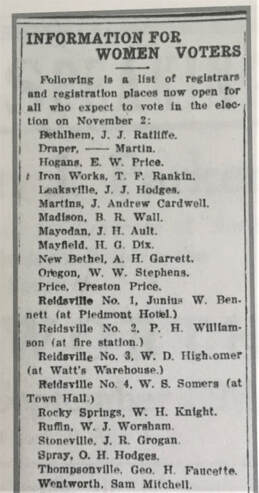

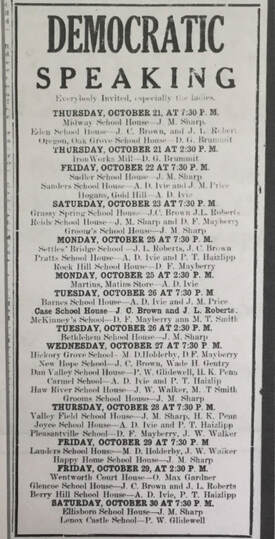

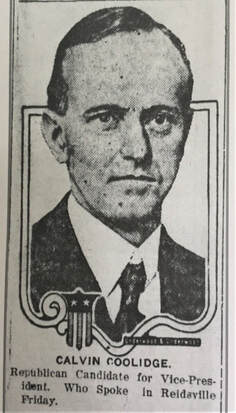

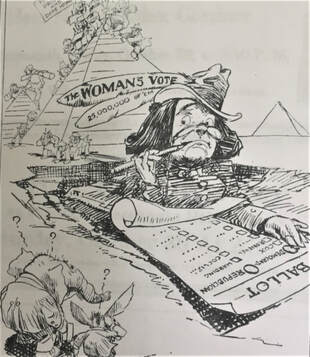

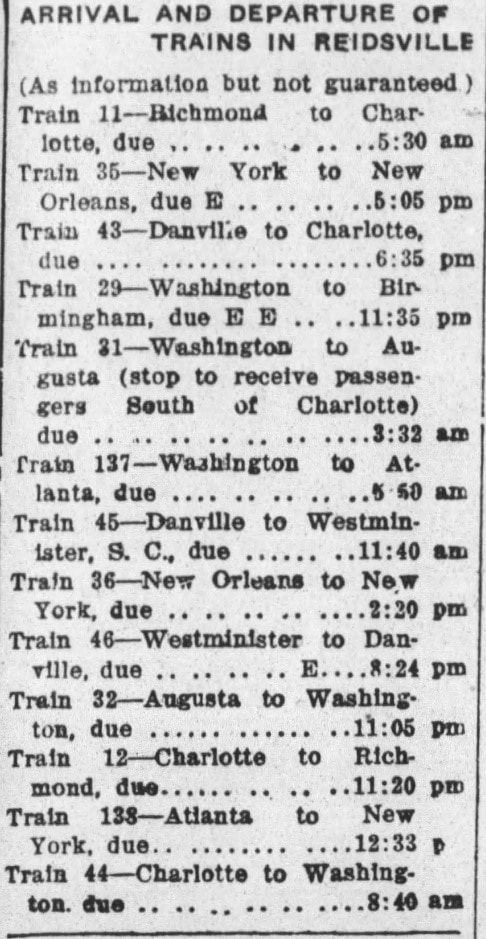

Jacqueline Dowd Hall, James Leloudis, et. al., Like a Family: The Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 1987), 126-139, (factory nursery, 134); Architectural Plans for Mayo Park and “Story of Washington Mills: Manufacturers of Mayo Spruce,” [mid 1950s?], Mayo-Washington-Tultex Mills Collection, 06-067, Rockingham County Historical Collections, Gerald B. James Library, Rockingham Community College, Wentworth, North Carolina, https://www.rockinghamcc.edu/library/findingaids/mayowashingtontultex.pdf; Interview of Connie Fox by author, July 12, 2021, Mayo River State Park, Mayodan, NC; Letters to and from U.S. Air Force to Town of Mayodan, May 26, 1976 and November 28, 1979, Scrapbook, Mayo River State Park; Antonin Raymond quoted in Architectural Record, 114, Scrapbook, Mayo River State Park; Reflections of Western Rockingham County, The Messenger, Randy Case and Deeanna Biggs, eds., (Marceline, MO: D-Books Publishing, 1993), 52, 56, 58, 71, 74, 89; Carla Bagley, “State To Save Park’s Historic Buildings,” Greensboro (NC) News & Record, December 7, 2005, B1, B2; Taft Wireback, “Mayo River: Park Gaining Momentum,” Greensboro (NC) News & Record, July 28, 2007, https://greensboro.com/news/mayo-river-park-gaining-momentum/article_51ad701a-e4fb-5d7c-a69b-6c1c4fca0b21.html; Articles from The Messenger, Madison, NC: “Formal Opening Ceremonies for Mayo Park Set for July Third,” June 17, 1948, 1; “Mayodan Game for Saturday Will Be Postponed,” July 1, 1948, 1; “Mayo Park Opening and Dedication Set for July 3,” July 1, 1948, 1; “Gala Throng Attends Mayo Park Dedication: Several Thousands Eat Barbecue and Enjoy Refreshing Swim,” July 8, 1948, 1; “Mayo Lake Will Open June 1,” May 19, 1955, 1; “Vespers at Mayo Lake Sunday,” June 9, 1955, 1; “Lifesaving Classes at Mayo Lake,” June 30, 1955, 1; Steve Lawson, “Architectural History in Our Own Back Yard,” May 13, 2005, 1, 6; Washington Mills Office Employees Photo Identifications: Front: Norris Griffin, Dr. T. B. Clay, Ben Archer, Bobbie James, Jane Pyrtle, Doris James, Violet Ledbetter, Margaret Tucker, R. B. Reid; Middle: unknown, unknown, Betty Jane Barrow, Emma Newman, Hazel Case, Ruby Lemons, Gladys Lundeen, Dot Ledbetter, Harvey Price, Rob Grogan, Red Drake/ Back: Virginia Payne, unknown, unknown, Peggy Myers, Clyde Johnson, Jane Richardson, unknown, Mildred Powers, Gretchen Sands, Ersell Minton, Otis Carter; Mayo Mills Band Identifications: Back L-R: Jesse Richardson, Jimmy Baker, Ross Myers, Kirby Reid, Frank Tulloch, Cecil Richardson, John Webb/ Front L-R: Sam Jones, Harold Myers, and Thomas W. Lehman, leader of band organized in 1915. May 1922Foreword by Dr. Debbie Russell - Local newspapers can provide us with many of the details of daily life in earlier decades. From the May 1922 pages of the Reidsville Review we get these glimpses of life in Rockingham County a hundred years ago. Many developments in the early 1920s were opening up new possibilities for Rockingham County residents—in communication, travel, and entertainment. Telephones were now in more homes and businesses, with an added advantage that the numbers would have been quite easy to remember with only two or three digits: 14 for Gardner Drug Company, 183 for the DeGrotte Coca-Cola Bottling Company, or 281 for Dr. W. I. Bowman, chiropractor. New paved roads and concrete bridges were planned for several areas. The county was set to receive a million and a half dollars in federal and state funds to improve infrastructure and facilitate travel. Hard surface roads to be built included an 8-mile stretch from Reidsville to Wentworth at a cost of $266,000, a 9-mile route from Gunn’s Store to Leaksville expected to cost $310,000, and even hard surfacing the road from Madison to Mayodan, a distance of two miles, at $60,000. Even in this era in the 1920s when North Carolina called itself the “Good Roads State,” automobiles were regularly mired in mud by a good rain. Automobiles were becoming more widely available and were advertised to local residents.

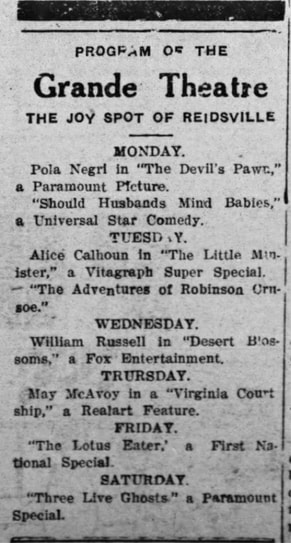

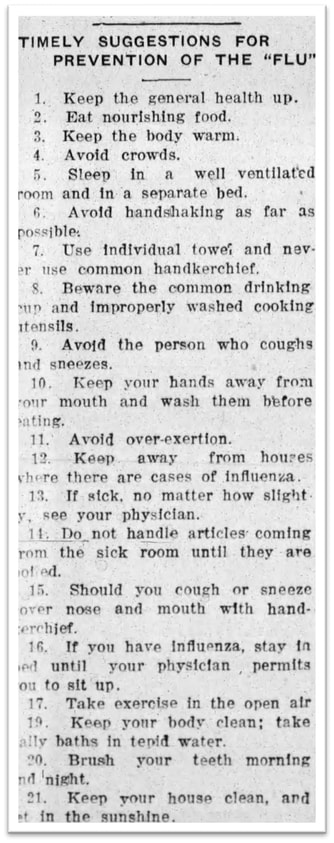

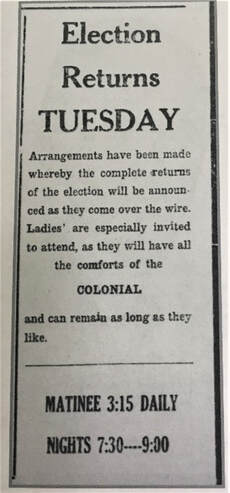

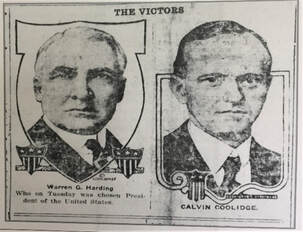

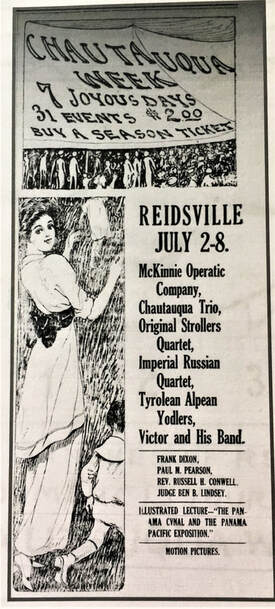

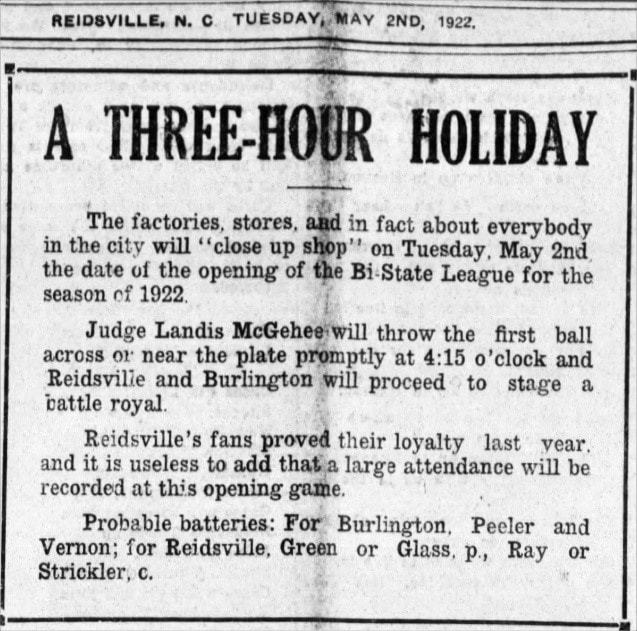

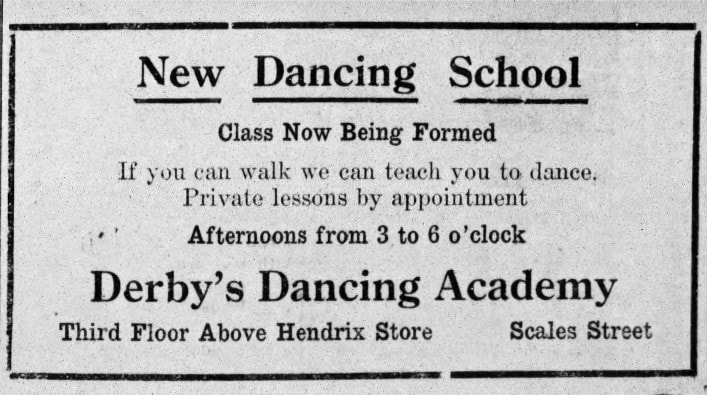

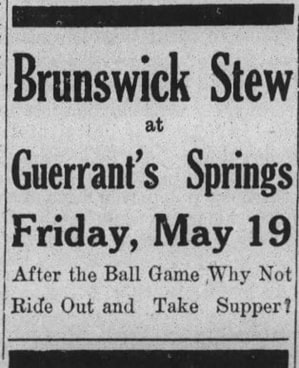

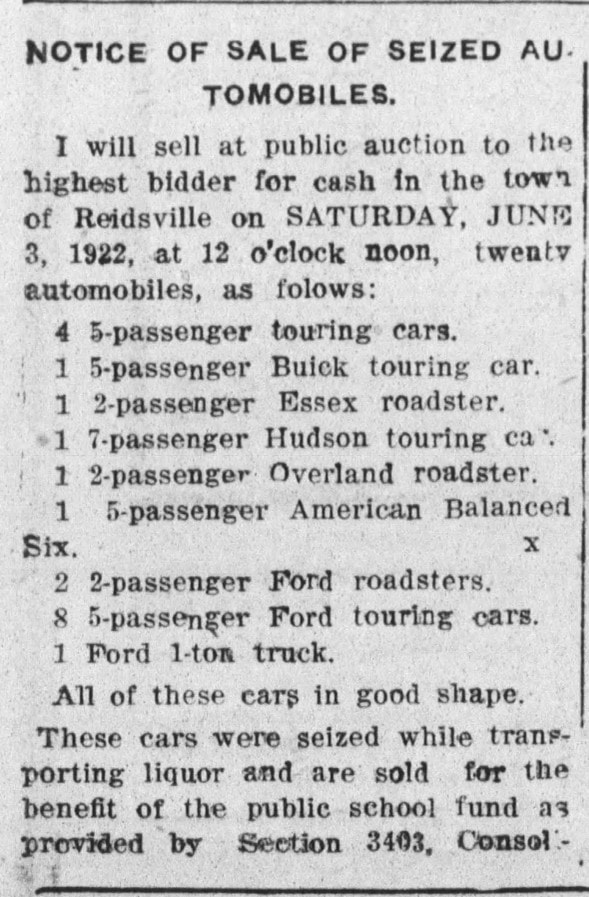

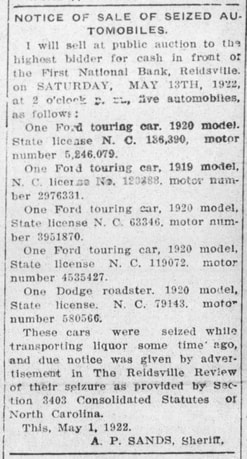

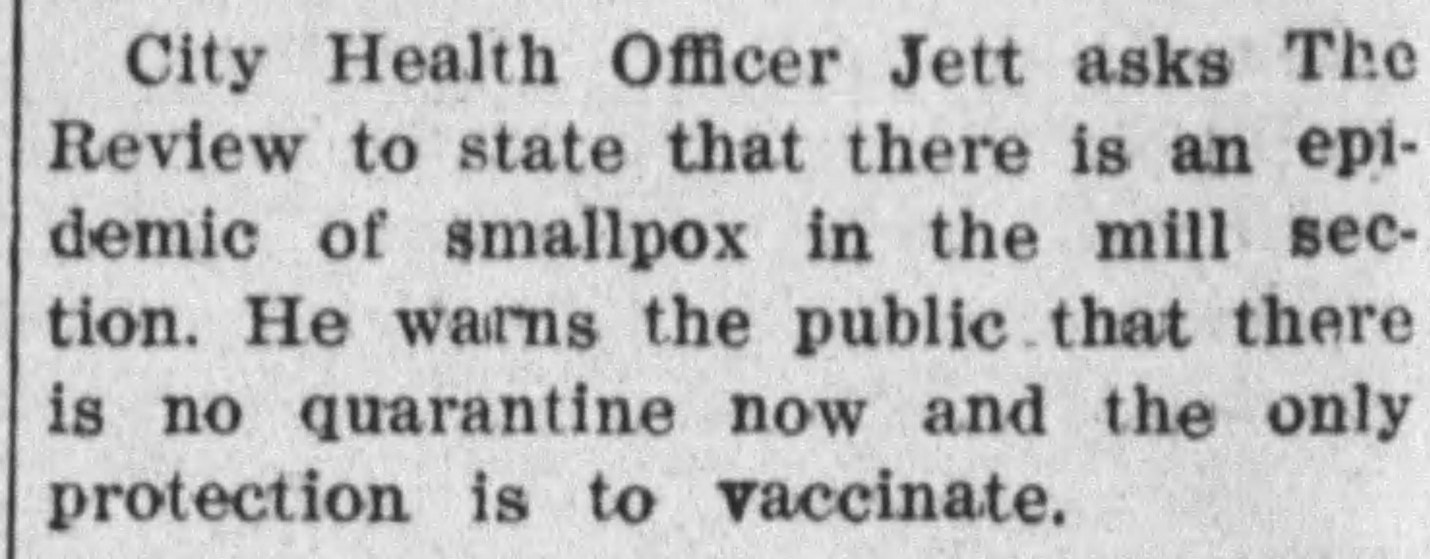

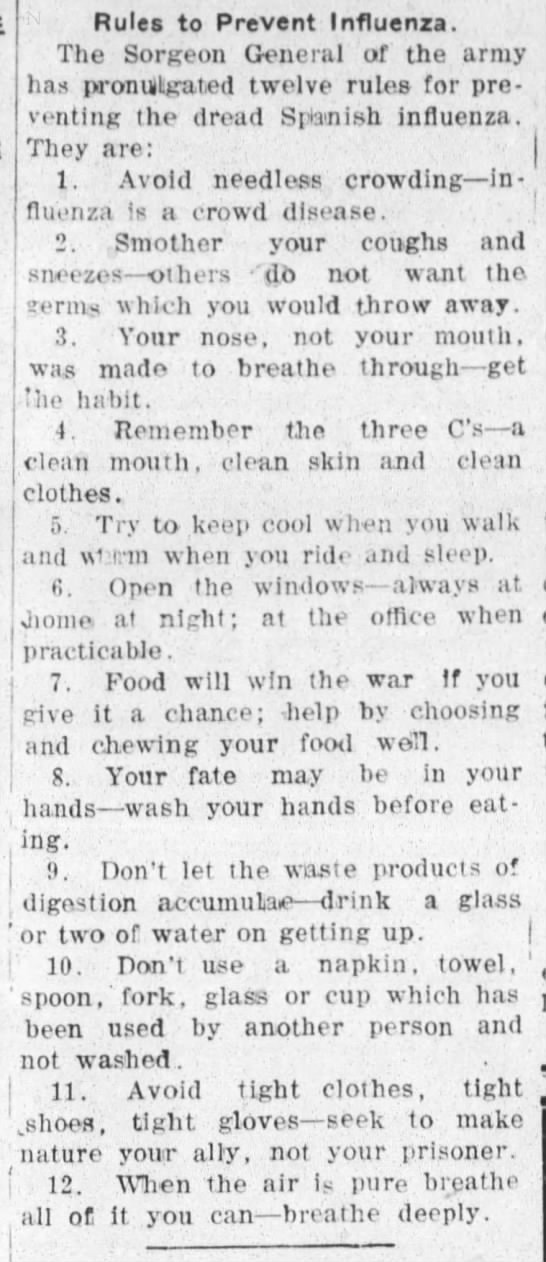

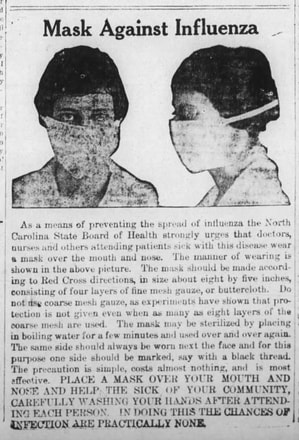

One hundred years ago, watching the new “moving pictures” was a possibility with the Grande Theatre showing the latest silent releases and sometimes even hosting live performances. Another interesting diversion in May 1922 was a well attended “spelling bee” for adults held at Lawsonville Avenue School. Over fifty adults, including “lawyers, doctors, preachers, teachers, and men and women of all professions,” participated in the event. Admission was 25 cents. Possibly the most anticipated activity in the area was the opening of the 1922 baseball season. Everything in Reidsville was shut down for a “three-hour holiday” on the afternoon of the opening games of the Bi-State League. The four-team League was comprised of teams from Reidsville, Schoolfield, Leaksville-Spray, and Burlington. At the games, patrons might have also had a refreshing Coca-Cola bottled in Reidsville at Fred DeGrotte’s company. The beverage was typically sold for 5 cents each. Other diversions that might have been enjoyed by Rockingham County residents in 1922 were dancing lessons at a new studio or attending a Brunswick Stew, one of the most popular activities in the area. A century ago, as now, interest in local elections was sometimes limited and at other times quite broad. Those who wanted to vote in many local contests frequently had to re-register in the weeks before each election, so involvement in local electoral politics sometimes took quite an effort. Only 37 people voted in the 1922 city elections in Reidsville. Five councilmen were elected—Dr. M. P. Cummings, G. E. Crutchfield, N. C. Thompson, W. B. Wray, and John F. Scott. These five were to select a mayor from among their number. In Madison, voters were somewhat more engaged in May 1922, approving bonds for a water and sewer system, 210 to 84. The “progressive element” in the community was “overjoyed at the victory,” the newspaper reported. With the 1920 suffrage amendment, women were taking on new roles in the aftermath of the world war, which was still heavy on the minds of folks in 1922. As reported in the Review, Mrs. B. Frank Mebane, member of the prominent Morehead family, continued her public service, traveling to Phoenix, Arizona, to give a talk on her war relief work in the Balkans. Yet, some of the developments in 1922 revealed a darker side of the times. Some area residents were clearly having difficulty complying with the anti-alcohol laws that had been instituted in January of 1920. Most of the cases brought to Superior Court in Wentworth were prohibition violations. Lawbreaking, called “showing disrespect of Mr. Volstead’s laws,” in one article, was widespread as evidenced by the list of automobiles confiscated by county law enforcement. In May 1922, Sheriff A. P. Sands advertised two public auctions of automobiles seized because of transporting illegal liquor. Funds from these sales were to go to the public schools. Public health in 1922 Rockingham County was also very concerning. Having recently come through years of the influenza pandemic, residents were no doubt alert to warnings from health officials about potential outbreaks of other serious diseases. Rotarians in Reidsville heard from the director of state sanitoriums who urged the county to build its own sanitorium to provide treatment for victims of tuberculosis. The county had seventy-five T. B. cases in 1921. Smallpox also was a serious threat in May of 1922 when the local health officer published his warning in the newspaper: Perhaps the most disturbing local report in May 1922 was the notification on the front page of the Review that a one-day-old infant (already deceased) had been thrown from a train as it passed through the area. The child, wrapped in newspaper, was found about six miles south of Reidsville between Troublesome Creek and Haw River. After notifying the coroner and unable to determine any further information about the baby, local authorities brought the infant into Reidsville for burial. Clearly, life one hundred years ago was, like today, a mix of both positive and negative moments. The pages of the local newspaper preserve details that give us more insight into the daily lives of those who lived in Rockingham County and are a valuable source for historical research. References

Articles and advertisements from the Reidsville Review, May 1922: Ad for Coca-Cola Bottling Company, May 2, 1922, 2; Ads for Dr. W. I. Bowman, Grande Theatre, Derby’s Dance Academy, and Gardner Drug Company, May 5, 1922, 2, 5, 6, 8; “Rotarians Hear T.B. Specialist,” May 5, 1922, 1; “One and Half Million Dollars for Roads in Rockingham County,” May 12, 1922, 1; “Mrs. B. Frank Mebane at the Arizona Road Congress,” May 12, 1922, 3; “Special Term Court Nears End—Regular Session Next Week,” May 12, 1922, 1; “Arrival and Departure of Trains in Reidsville,” May 12, 1922, 6; “Bi-State League,” May 5, 1922, 4, and May 12, 1922, 4; “News of Reidsville and Rockingham,” May 5, 1922, 5 and May 16, 1922, 5; Advertisement for Reidsville Motor Company, May 16, 1922, 3; “J. A. Jones Leases City’s New Hotel,” May 19, 1922, 1; “Excursion to Washington, D.C.,” May 23, 1922, 3; “Of Local Interest,” May 23, 1922, 5; “Reidsville Now Has a Landing Field,” May 26, 1922, 1; “Notice of Sale of Seized Automobiles,” May 16, 1922, 6, and May 26, 1922, 5; “Happenings in the Town and County,” May 26, 1922, 5. February 1924Introduction by Dr. Debbie Russell: One of the most noted court cases in the county’s history had its roots in February 1924, when the Rockingham County Board of Commissioners decided to cancel a contract to build a bridge across the Dan River. They had just approved the contract with the Luten Bridge Company of Tennessee on a vote of 3-2 a month earlier at their regular meeting in the 1907 Courthouse (now the location of the MARC). In the intervening weeks, a very vocal opposition movement and a new member appointed to the Board of Commissioners resulted in a vote to rescind the contract. Despite the cancellation of the contract, the company went ahead and completed the bridge anyway, and then sued the county to recover their costs. Spanning the river at Fishing Creek in the Leaksville area, this made the third bridge across the river within a distance of less than two miles. The scenario had started months before, involved some of the most prominent citizens in the area, and for a time seriously divided Rockingham County into those for and opposed to building the bridge. The controversy included accusations of manipulation by influential leaders, two thousand protesters at one meeting, resignations, new appointees, scores of newspaper articles for and against the bridge, and ultimately court filings that went back and forth for more than a decade. In fact, in the legal world, the Rockingham County v. Luten Bridge case has become a staple of contract courses and is now studied in virtually every law school in America. Other legal analysts have also noted its importance in local government law, in addressing the legitimacy of elected and appointed boards and their role in economic development. The story behind this fascinating case and what was called both “the bridge to nowhere” and “the most beautiful bridge in the South” is covered in local historian Bob Carter’s article from the Journal of Rockingham County History and Genealogy (June 2004) found below. Keep reading to find out the history of one of Rockingham County’s most important court cases. A Bridge To Nowhere - by Bob Carter (County Historian)(read using the slides below or by downloading the PDF)

References:

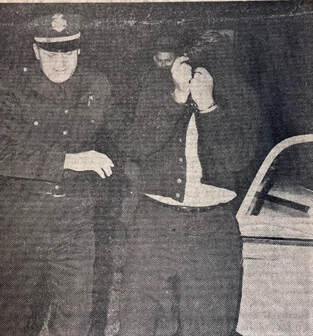

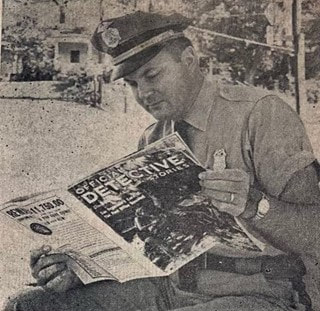

In addition to those cited in Bob Carter’s Journal article, the following sources might also be of interest to readers: Articles from The Tri-City Daily Gazette (Leaksville, NC): “Mass Meeting Is Called Monday, February 4,” January 17, 1924, 1, reprinted from The Reidsville Review; “Democratic County Chairman Condemns Mass Meeting and Upholds Orderly Government,” January 30, 1924, 1; “Madison Man Pleads To Put Down Strife,” January 31, 1924, 1; “3 County Commissioners Bring Suit,” February 2, 1924, 1; “Mass Meeting Did Not Accomplish Its Purpose Yesterday,” February 5, 1924, 1; and a series of commentaries from the Gazette editor, Murdoch E Murray, entitled “A Tale of a Bridge” from February 8- March 8, 1924, in which he generally supports B. Frank Mebane and the building of the bridge. See also Rockingham County v. Luten Bridge Co., 35 F.2d 301 (4th Cir. 1929), Justia, US Law, https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F2/35/301/1488369/; Barak Richman, Jordi Weinstock & Jason Mehta, “A Bridge, a Tax Revolt, and the Struggle to Industrialize: The Story and Legacy of Rockingham County v. Luten Bridge Co.,” 84 N.C. Law Review, 1841 (2006), https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol84/iss6/2; Donnie B. Stowe, “Mr. Mebane’s Bridge and the Railroad That Never Was,” Rockingham County Legacy: A Digital Heritage Project, Original in Linda C. Vernon Genealogy Room, Rockingham County Public Library, Madison, NC, Digital NC, https://lib.digitalnc.org/record/101073#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&r=0&xywh=299%2C438%2C1936%2C1176; Brenda Marks Eagles, Benjamin Franklin Mebane, Jr., NCpedia, State Library of North Carolina, https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/mebane-benjamin-frankli-0; and Helen Lounsbury, “The Bridges of Rockingham County: Quite a Tale Could Be Written about Local River Spans,” January 6, 1994, News & Record (Greensboro, NC), https://greensboro.com/the-bridges-of-rockingham-county-quite-a-tale-could-be-written-about-local-river-spans/article_61085f9a-38fc-5d14-acef-f4b9debe6e50.html This Month in Rockingham County History: January - 'McAnally Theft One of the Largest in NC History'1/24/2022 January 1963 (Above: The McAnally safe now in the MARC collections. The safe was stolen in January 1963 and recovered months later from High Rock Lake. Its contents were worth about $130,000. Photo by J. Bullins.) (Above: The McAnally safe now in the MARC collections. The safe was stolen in January 1963 and recovered months later from High Rock Lake. Its contents were worth about $130,000. Photo by J. Bullins.) On a chilly January afternoon in 1963, a safe full of cash, stocks, and bonds was stolen in broad daylight from the home of Madison dentist Dr. C. W. McAnally. It was believed to be the largest theft in the state of North Carolina up to that time. When the thieves opened the safe at a cabin near High Rock Lake in Davidson County, even they were surprised by the remarkable amount inside—about $130,000 in all. The victim and law enforcement, led by Madison Police Chief Paul Case and officers from the State Bureau of Investigation (SBI), pieced together the details of the robbery. On January 17, Dr. McAnally had walked from his upstairs dental office on Murphy Street back to his home for lunch around 11:40. After his midday meal, McAnally testified, he sat for a while and looked out his window, where he noticed someone behind a tree in the yard, where the man (later identified as one of the thieves) stood for about fifteen minutes. McAnally then saw that man walk across the street and speak to another who was waiting at the car dealership there. Just before one o’clock, the dentist locked the front door, put the key where it was usually left in a hanging wicker basket on the right side of the door, and walked back down Market Street the block and a half to his office. When McAnally returned home around five, he found the front door unlocked and the key and basket on the floor just inside the entryway. He checked the back door and found it was also unlocked. He then realized that his safe had probably been taken and went to the closet where it had been hidden. The 150-pound metal safe, where McAnally had placed the cash and important financial documents decades earlier, was, in fact, gone. Three men were eventually arrested, tried, and convicted of the crime. Two—Joseph Thomas Watkins, 35, and Howard Eugene Knight, 32, who had entered the home and stolen the safe—were arrested only four days after the robbery. The third, Henry Lewis Leonard, 32, of Lexington, was not arrested until April. In February, McAnally thanked the Madison Police Department for their quick action leading to the arrest of Watkins and Knight by giving the department a check for a needed piece of equipment—a $600 two-way walkie-talkie—that would help them patrol the town.  (Above: Suspected thief Howard Eugene Knight covers his head as he is taken into the jail in Wentworth by Madison Police Chief Paul Case. Photo from The Messenger (Madison, NC), January 24, 1963, 1.) (Above: Suspected thief Howard Eugene Knight covers his head as he is taken into the jail in Wentworth by Madison Police Chief Paul Case. Photo from The Messenger (Madison, NC), January 24, 1963, 1.) The theft unfolded this way: News had circulated in the area and eventually among the criminal crowd that McAnally kept a large amount of cash in his home. The trio of thieves, who had served time in and become well acquainted with NC jails over the previous decade, may have heard that one area resident had had a large insurance check of $1800 cashed by the dentist in his home after hours. Leonard suggested the dentist as a target to Knight and Watkins and drove the get-away car, a blue and green Mercury they had borrowed from an acquaintance in Greensboro. Two local men later told authorities that they had seen this car parked beside the McAnally house. On the afternoon of January 17, 1963, the two robbers entered the dentist’s home with the key and found the safe in the closet. Watkins was able to lift the heavy safe and carry it out the back side door. They put the safe in the back seat of the car and Watkins sat there beside it. Next, the thieves stopped at a hardware store in High Point, where Watkins bought a screwdriver and a crowbar. He had learned to crack open safes while on the lam after a prison escape in the mid-1950s and boasted later that he had the McAnally safe open in less than ten minutes. The robbers then took the stolen safe to a cabin owned by Leonard’s father at High Rock Lake. “It was full of money, most money I'd ever seen in my life,” Watkins later told a reporter. “I was really surprised. All of us were.” There were so many bills that they had to use two bunk beds at the cabin to stack and examine their haul— hundreds, fifties, twenties, and a few smaller bills. As the prosecution later described the cash for judge and jury, “This money, by reason of being kept for years in his safe, had a moldy, stinky odor.” Several witnesses testified that bills given to them by the defendants also had this very identifiable “moldy” smell. In the days immediately following the heist, the trio of thieves traveled to Greensboro, Salisbury, and Fayetteville and had dealings with many people across the state, including family members, gambling pals, and military police. They had a female acquaintance return the vehicle they had used during the theft to the home of its owner in Greensboro and both Watkins and Knight bought cars. Knight paid a dealer, the father of Henry Lewis Leonard, $2100 for a 1961 Chevrolet on January 18, and the teller who received this deposit later testified that the bills had a “foul” odor. On the morning of January 19, military police stopped Watkins as he was “weaving” on a highway near Fort Bragg and charged him with drunk driving. Watkins paid the $300 bail with fifteen twenty-dollar bills from his stash. Officials later testified that there was a “distinct odor of mustiness, an unpleasant odor to the money.” Watkins was arrested at the home of his sister in Greensboro, but only after a surprising mix-up. The day after the robbery, he had left some cash (about $300) and a suitcase full of what he thought was dirty clothing at her home. When the sister opened the case, she found a pillowcase filled with what turned out to be about $15,000 in very “moldy” smelling bills. The money smelled so bad, she told authorities, that she sprayed the room with an air deodorizer. She called her husband and her father and upon showing them the contents of the suitcase, they called the police. Meanwhile, Watkins had realized his mistake while gambling in Fayetteville when he went to the car to get more cash, finding instead his dirty laundry. When he arrived at his sister’s home to retrieve the suitcase, he was met with a “double-barreled shotgun” and law enforcement officers who arrested him. Watkins told the SBI that he had won the money gambling. Somewhere around $17,000 of the large cash haul was eventually recovered, mostly from Watkins’ share of the money. It is not clear what happened to the rest. Knight was later apprehended by police in Charlotte and brought back to Rockingham County, where he and Watkins were initially held on bonds of $150,000 each. At the trial in Wentworth in June, McAnally was asked to identify the recovered bills as those he had stored in the safe in his Madison home some twenty-five to thirty years earlier. Although he could not confirm the bills were his from serial numbers or markings, he testified that he could do so another way—by their distinctive odor. To challenge him, the defense attorney took two bills out of his own wallet, mixed them in with others recovered from the accused thieves, and shuffled the stack. The dentist “closed his eyes and sniffed each bill separately,” saying “yes” to each of the recovered bills and “no” to the attorney’s money. The jury also “smelled” the money entered as evidence. The judge at the trial in the Rockingham County Courthouse (now the MARC building) explained to the jury the role of circumstantial evidence, as some of the details in the McAnally case fell into this area of the law. After deliberating only thirty minutes, the jury convicted Knight and Watkins of breaking and entering and larceny and sentenced them each to fifteen years in prison. Their accomplice Leonard would later receive the same outcome and sentence when he stood trial. Defense attorneys appealed the convictions to the North Carolina Supreme Court, which held that no errors had occurred that would warrant a new trial. Details of the heist as presented in court were confirmed and additional information was given in an interview of one of the accused with a Greensboro reporter in the early 1990s.  (Above: Police Chief Paul Case examines the story about the McAnally safe theft in the August 1963 issue of Official Detective Stories. Case disputed many of the "facts" presented in the article titled "Sleuthing Behind Prison Walls." The Messenger (Madison, NC), July 4, 1963, 1.) (Above: Police Chief Paul Case examines the story about the McAnally safe theft in the August 1963 issue of Official Detective Stories. Case disputed many of the "facts" presented in the article titled "Sleuthing Behind Prison Walls." The Messenger (Madison, NC), July 4, 1963, 1.) The case fascinated the public. Much of the evidence was a bit unusual—the surprisingly large amount of money kept at home rather than in a bank, the robbery carried out in broad daylight on a downtown street, the “mixed-up” suitcases (one filled with money, the other with dirty clothes), and, most of all, the references by multiple witnesses to the foul, pungent odor of the bills. The case was even written up in a true-crime magazine. The article in the August 1963 issue of Official Detective Stories, however, went too far in embellishing details about the robbery, according to the police chief who headed the investigation. Paul Case saw the article as "90% wrong,” he told local reporters. The only parts the detective magazine writers got right were “my name, Dr. McAnally’s name, and the name of the town,” he said. At the time of the robbery, Dr. McAnally was in his late 60s and had practiced dentistry in Madison for forty years. He died in 1974, leaving an estate valued at about a million dollars. Prior to the 1963 McAnally robbery in Madison, the largest theft in North Carolina was likely in the early 1930s in downtown Charlotte, when a gang took $100,000 from a mail truck. The offices of the Dodson Shelton Nelson accounting firm now occupy the McAnally house and artifacts related to the heist are now in the MARC collections. These include the metal safe, which was recovered from High Rock Lake in about thirty feet of water and given to the museum by McAnally’s daughter, Lib McAnally Folger Apple. References: