|

In the final year of World War I, a deadly outbreak of influenza (and the pneumonia that often accompanied it) hit North Carolina, ultimately taking 13,644 lives across the state. More than 700,000 died nationally. Many have expressed an interest in learning more about how this 1918 influenza epidemic, quickly becoming a pandemic, affected Rockingham County. Local historian Debbie Russell and author of our 'This Month in Rockingham County History' articles, has kindly stepped in to research the 1918 epidemic's toll on the County for our July newsletter article, as Bob Carter protects his health while staying at home. Thank you Debbie for your tireless efforts and thorough and fascinating research. How many more will die in this pandemic? How long will schools be closed? What can we do to stop the spread? Will my business survive? When will we get to return to church? These are all troubling questions that loom as we try to work through our current COVID-19 crisis. One hundred years ago, Rockingham County residents were facing some similar questions as they dealt with a devastating influenza outbreak—what has been called the 1918 Spanish flu. Because Spain was not involved in fighting WWI, the Spanish government did not withhold news of the influenza outbreak there as other countries did. And, because the public heard of the Spanish king’s bout with the flu early in the outbreak, many assumed the epidemic had started there. While there is still debate about the influenza’s origins, there is credible evidence that some of the earliest cases were identified by a doctor in Haskell County, Kansas, in February 1918, and that the infection had spread to American troops at Camp Funston in that state by March 4. The disease spread rapidly—with more than 29,000 cases in the army camps alone by September 27. Public health officials of many agencies, including the war and navy departments and the Red Cross, conferred about the alarming conditions and attempted to implement measures to combat the influenza’s spread, but the outbreak traveled along with the increased movement of people, especially soldiers in training camps and deploying to Europe. In early October, three “Leaksville boys in army service” at military camps in Louisiana, Seattle, and Boston—Robert Martin, Will Hodges, and Frank Rainey—were among the victims of the influenza. The first case reported in North Carolina was in Wilmington, where a 29-year-old father of two became the state’s first recorded victim. The port city was so hard hit, with 500 additional cases in a week, that local leaders set up a special hospital for influenza patients by the end of September. In the coming weeks, the disease quickly spread west across the state, especially along railroad lines. Governor Thomas Bickett issued a call for North Carolinians to stay home and protect themselves. In early October, Raleigh was said to be in the “grip” of influenza, with 50 girls at St. Mary’s School, 75 boys at the A & E College, and another 125 people across the city and Wake County infected. Mill villages were hard hit with infection. By mid-October, Rockingham County residents heard that the influenza was “on a rampage” in Roxboro, two counties east. There, thirteen funerals were held on one Wednesday alone and 600 more influenza cases were “without medical attention.” “It is said,” the Reidsville newspaper reported, “there are not enough well men to shroud the dead.” Local folks also heard of the death of the young president of the University of North Carolina, Edward Kidder Graham, who lost his life to the virus on October 26.

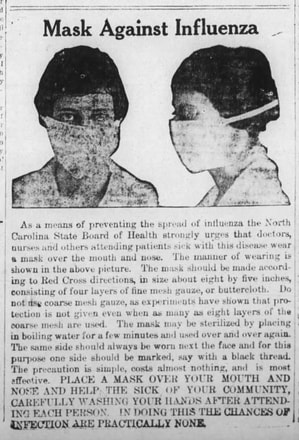

Local officials acted quickly. To prevent the spread of the deadly virus, a general shutdown of the city of Reidsville was ordered on October 7. The health ordinance closed all schools, churches, and theaters, and prohibited public gatherings of all kinds. Violators were to be fined $100 for each infraction of the ordinance. An emergency hospital was opened in the Lawsonville Avenue School building to take care of influenza patients. Mr. Francis Womack, Red Cross chairman, issued a call for additional nurses to staff the hospital. “It is gratifying that some have so nobly responded,” he said. “But we want more to volunteer for this noble work.” When the influenza situation seemed to improve by the end of the month, the emergency hospital was closed. Medical professionals offered guidance. The Surgeon General of the Army advised, “Avoid needless crowding—influenza is a crowd disease.” He also suggested opening windows, keeping cool, and washing hands. The North Carolina State Board of Health published instructions for making and using masks when attending the sick. The masks, according to Red Cross instructions, were to be eight by five inches and made of four layers of gauze. To sanitize them, masks could be placed “in boiling water for a few minutes and used over and over again.” Citizens were urged, “Place a mask over your mouth and nose and help the sick of your community.” Numerous advertisements began to appear in newspapers promoting the use of various tonics and treatments for the influenza and pneumonia spreading in the region. Some ads were designed deceptively in formats that appeared to be news articles. Some were remedies that had been available for decades.

More Advertisements from 1918To reduce the epidemic’s impact, public activities were curtailed in October 1918. Long-planned community fairs in Bethany and Reidsville were postponed. Political meetings, including Governor Thomas Bickett’s speech in the New Bethel community, had to be cancelled. Still citizens were urged to vote in the upcoming November election. As long as crowds did not congregate at polling places, “There is no reason why any voter who is able to be outdoors should fail to exercise the right of franchise because of fear of this disease,” health officials assured the public. Churches also had to adapt during the influenza crisis. Some churches made requests for donations and tithes of their members during the shutdown. “Our church has been closed for several weeks on account of influenza,” the leaders of St. Thomas Episcopal Church wrote, but “our expenses are necessarily going on.” They asked the congregation to bring or send their dues to the church during a designated hour when the treasurer would be waiting there. When Reidsville houses of worship were closed by the town health directives, one minister was reported to have gone a bit outside the town to preach at a church in Wentworth one Sunday morning.

Boy Scouts rang the bell at the Reidsville First Presbyterian Church each night for a week in November to remind citizens to pray for the soldiers and for an end to the epidemic. Commerce was also affected. One observer noted, “The influenza epidemic has played smash with business in all sections of the State.” Even though several tobacco markets, including Winston-Salem, had already been closed, local pundits predicted on October 15, “No shutdown of the tobacco market, factories or stores are contemplated here.” However, to check the spread of the epidemic, state health authorities did request that tobacco warehouses close, which they did in Rockingham County on October 18. Tobacco warehouse managers worried that some of their competitors in the county would open before the lifting of the health ordinance. Having missed some important weeks in the tobacco trade, all were permitted to reopen on November 4, “the influenza epidemic having improved to such an extent that it was deemed safe to resume the sales.” The epidemic also brought disruption to local schools. Young teachers who had been working away in Jackson Springs and Gastonia returned home to Rockingham County in mid-October, their schools having closed “until the influenza epidemic is over.” The rural Bethany School was closed for two weeks but reopened by October 29. Schools in Reidsville were closed by the October 7 ordinance and reopened on November 11. Doctors assured families that it would be safe to return then and urged parents not to keep their children away from their classes. During the month of October 1918, at least 5,000 in North Carolina died from influenza and the pneumonia that often followed, with 55 of these victims being in Rockingham County. The first “crest of the epidemic was apparently reached during the fourth week of October,” the State Board of Health reported. The human toll was great. One of the local victims that week was 35-year-old Walter Ledbetter, “a well-known citizen of Madison,” who died after a “short illness with influenza,” leaving a wife and “five little children.” In early November, it seemed to many that the worst might be over locally. One Stoneville resident praised town officials for their careful leadership. “There have been only three cases of influenza within the corporate limits,” he said, and only “seven or eight in the community near here.” A young Wentworth woman home during the epidemic returned to her studies in Greensboro when the college reopened. The Reidsville library, which had been closed for six weeks, reopened in mid-November. Patients seemed to be recovering. The newspaper noted that Dr. W. A. Johnson of Monroeton was “out again after recovery from a hard spell of influenza and pneumonia.” It was reported that Miss May Hopper was now well and able to go back to school and that several others were “convalescing after an attack of influenza.” North Carolina Governor Thomas Bickett proclaimed a day of Thanksgiving for Sunday November 17, “rejoicing both for the victory that has attended American and allied arms and for the passing of the terrible epidemic.” However, outbreaks in various communities of Rockingham County flared again and continued into December. A McIver resident reported that “the influenza is again epidemic in his section.” Both black and white families were stricken. Manton Oliver, whose family operated the Reidsville newspaper, found himself “confined to his room with influenza” as it was declared that “the influenza situation continues bad here.” In the New Bethel township, there were “quite a number of influenza cases.” Mr. T. Z. Sparks of the Oregon section told the newspaper that “nearly all of his family have been down with the influenza.” A citizen of the Mt. Carmel area reported that the influenza epidemic continued to “rage” in that community, saying “The influenza is taking a new start in this section and we fear it will yet get in the schools.” By Thanksgiving 1918, over 80,000 Americans had died from the epidemic and news of deaths locally was frequent in this second wave of infection. Among the victims was 27-year-old Edna Johnston of Reidsville, who died of influenza-pneumonia only weeks after her brother Jamie had died from the same malady. Alvis Daniel Millner, age 51, died from influenza on December 4 after being ill for only two days. Mrs. Irvin T. Hinton and her four-year-old son Earle died during the first week of December and were buried the same day. Five others in the Hinton home also had influenza-pneumonia. On November 27, acting on the “advice of the city health officer and other physicians,” Reidsville again adopted an ordinance closing schools, the public library and churches. While in effect, the ordinance made it unlawful to operate “any motion picture or vaudeville show” or to hold any public meetings or gatherings. As with the earlier ordinance, all homes where influenza victims had died or had been nursed back to recovery had to be disinfected according to directions from the county health officer. This time, though, the fine for violating any of the directives was $50, half of the fine imposed two months earlier. During the second shutdown, the county school superintendent assured parents and children that the “time lost on account of the influenza will be made up during the spring term and that grades will be promoted.” High school teachers promised to give the senior class an extra month to complete all work required for graduation. The week before Christmas, Madison High School announced that its principal, J. C. Lassiter, had influenza and that the school would close again and not reopen until after the holidays.

The span from September through December was certainly a time of great concern for Rockingham County and all of the state. Besides the trauma of influenza deaths, many local families were hoping to hear that their soldiers were returning home from the war, but instead often received sad news that their loved ones were injured or missing in action. Other serious health concerns were present in the county as well in the fall of 1918. Two dozen Rockingham County patients were quarantined with diphtheria, in addition to 37 with typhoid and 14 with smallpox.

By the new year, the influenza epidemic seemed to be waning. The renovated Grande Theatre in Reidsville announced that it was properly ventilated and reopening in compliance with health ordinances. Students were back in school and in Reidsville were attending classes a half day on Saturdays in January to make up for lost instruction. Still, national health officials warned that the public should learn from the “bitter experience” of the epidemic, to “realize the seriousness of the danger,” and to expect “a large number of scattered cases” in the coming months. Emphasizing the ongoing concern about infection, one business reminded the public repeatedly in its January 1919 ads, “Our store is disinfected daily against spread of disease.” As the new year began, one Ruffin resident wrote that folks in his area were very thankful that all but one of the soldiers from their community had returned safely from the war and that the “flu situation in our town is greatly improved.” “Many homes are in mourning,” the editor of the Reidsville paper wrote. “We have had to mourn in common with other localities the loss of some of our brightest young men who have made the supreme sacrifices of war, as well as men and women who succumbed to the ravages of the influenza epidemic.” The year 1918, he concluded, had brought “strange, startling, and unprecedented” times. Sources: Western North Carolina Historical Association, “1918 vs. 2020: Epidemics Then and Now in NC,” Online Exhibit, https://www.wnchistory.org/virtual-exhibits/influenza/; John M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History (New York: Viking Penguin Group, Inc., 2004), 92-97, 338, and 355-356; Kip Tabb, “Historic Outbreak: Spanish Flu on NC Coast,” North Carolina HealthNews,https://www.northcarolinahealthnews.org/2020/05/02/historicoutbreak-spanish-influenza-on-nc-coast/ ; Going Viral: Impact and Implications of the 1918 Flu Pandemic, Online Exhibit, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Wilson Library, https://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/exhibits/show/going-viral/goingviral; Steve Case and Lisa Gregory, “Influenza Outbreak of 1918-1919,” NCpedia, Government and Heritage Library, State Library of North Carolina, https://www.ncpedia.org/history/health/influenza; William S. Joyner, “Infectious Diseases,” NCpedia, Government and Heritage Library, State Library of North Carolina, https://www.ncpedia.org/infectious-diseases part-ii . Articles in the Reidsville (NC) Review: “Spanish Influenza Prevalent,” September 27, 1918, 1; “Raleigh in Grip of Spanish Influenza,” October 1, 1918, 1; “Rules To Prevent Influenza,” October 22, 1918, 5; “A Call to Prayer,” October 25, 1918, 1; “Route 6,” November 26, 1918, 4; “Health Ordinance,” December 3, 1918, 6; and December 6, 1918, 7; “University President Dead,” October 29, 1918, 1; “Thomas S. Beall Dead,” October 8, 1918, 1; “Emergency Hospital Opens in Reidsville,” October 25, 1918, 1; “Spanish Influenza—New Name for Old Familiar Disease,” October 25, 1918, 6; “Editorial Column,” October 15, 1918, 4; “Stoneville,” November 5, 1918, 3; “Influenza Should Not Stop Voting,” November 5, 1918, 3; “Bethany,” October 29, 1918, 4; “Schools Will Make Up Lost Time,” December 3, 1918, 1; “Tobacco Warehouses To Open November 4,” October 29, 1918, 1; “Mt. Carmel,” November 22, 1818, 5; and December 13, 1918, 4; “A Call to the Good Samaritans,” December 6, 1918, 8; “U.S. Health Service Issues Warning,” December 13, 1918, 6; “Notice,” November 1, 1918, 8; “Should Be Forced To Close,” October 22, 1918, 4; “1918-1919,” December 31, 1918, 4; “Ruffin,” January 3, 1919, 5; “County Quarantine Officer’s Report,” October 8, 1918, 7; November 12, 1918, 1; and December 6, 1918, 2; “Some Timely Advice to the Influenza Convalescents,” December 2, 1918, 6; “Madison High School,” December 17, 1918, 1; “In Memoriam,” December 17, 1918, 4; “News of Reidsville and Rockingham,” November 26, 1918, 5; “Review of the Town and County News,” October 4, 1918, 8; October 8, 1918, 8; October 11, 1918, 8; October 15, 1918, 8; October 18, 1918, 8; October 29, 1918, 8; November 1, 1918, 8; November 5, 1918, 8; November 8, 1918, 8; November 12, 1918, 8; November 15, 1918, 8;November 26, 1918, 8; November 29, 1918, 8; December 3, 1918, 8; December 6, 1918, 8; December 13, 1918, 4; December 17, 1918, 8; December 31, 1918, 8; January 14, 1919, 8; “City Local News in a Condensed Form,” November 15, 1918, 5; November 29, 1918,1; December 3, 1918, 1; December 6, 1918, 1; December 13, 1918, 1; December 20, 1918, 1; December 31, 1918, 5; Advertisements in the Reidsville (NC) Review: Rockingham County Fair, September 20, 1918, 2; Mask Against Influenza, November 5, 1918, 5; Hill’s Bromide Cascara Quinine, November 8, 1918, 2; November 15, 1918, 4; November 22, 1918, 6; and November 29, 1918, 6; Foley’s Honey and Tar, November 22, 1918, 4; and November 29, 1918, 8; Dreco, November 5, 1918, 7; How To Use Vick’s VapoRub in Treating Spanish Influenza, October 18, 1918, 2; Druggists!! Please Note Vick’s VapoRub Oversold Due to Present Epidemic, Vick Chemical Company, October 29, 1918, 6; Vick’s VapoRub, November 8, 1918, 7; Peruna, October 29, 1918, 2; S. S. Harris, Clothier, December 24, 1918, 4; A. S. Price & Co., December 3, 1918, 8; January 3, 1919, 3. Reidsville Review accessed through NCLive, nclive.org, Historic North Carolina Digital Newspaper Collection, https://newscomnc.newspapers.com/ .

1 Comment

Clelia S Casey

7/28/2020 12:38:34 pm

My grandfather, Dr. M..B Abernethy,, was a practicing physician in Reidsville during the epidemic and also in charge of the hospital corps of the National Guard there. The Guard was called up to fight in Europe while he was sent to New York harbor to treat returning soldiers on hospital ships who had contracted the flu. Evidently, he never caught it.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Articles

All

AuthorsMr. History Author: Bob Carter, County Historian |

|

Rockingham County Historical Society Museum & Archives

1086 NC Hwy 65, Reidsville, NC 27320 P.O. Box 84, Wentworth, NC 27375 [email protected] 336-634-4949 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed