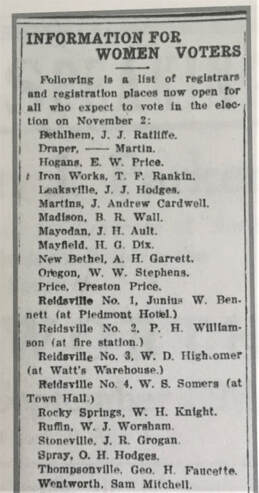

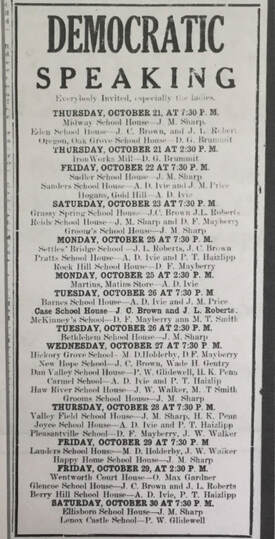

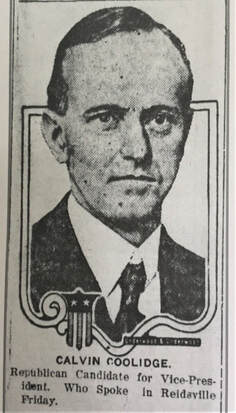

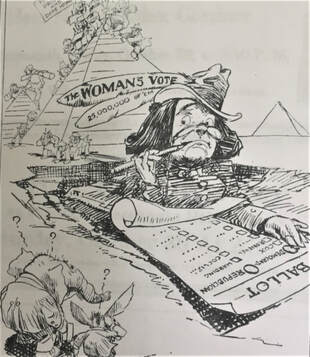

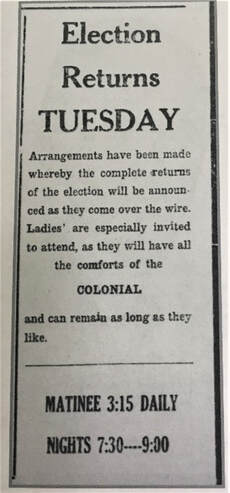

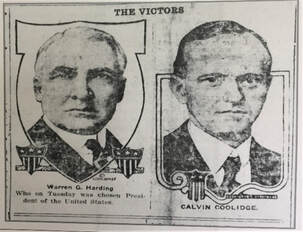

September 1920 (List of Precincts and Registrars, 1920/ "Information for Women Voters," Reidsville Review, October 1, 1920, 1.) (List of Precincts and Registrars, 1920/ "Information for Women Voters," Reidsville Review, October 1, 1920, 1.) In September 1920, the campaign to register newly enfranchised women voters began in Rockingham County. The lead-up to the 1920 election was a spirited time when local women heard passionate appeals from both political parties and then voted “for the first time in their lives.” In some areas of the state, it was feared, there would be “something on the order of an upheaval” because women were voting, but, according to one observer, “no unusual occurrences” were anticipated in Rockingham County, “except the sight of the feminine appearances at the election booths.” Voter registration for women started only a month after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment on August 18, 1920, and was expedited because of the fast-approaching election on November 2. The registration books for all county precincts were open for twenty-one days, excluding Sundays, from Thursday, September 30 through Saturday, October 23. Residence requirements were that the new voters had to have lived in the precinct thirty days, in the county six months, and in the state for two years in order to be eligible to cast their ballots. In each issue of the Reidsville newspaper during this time, “every woman in the county qualified for the ballot” was urged to register and vote. “Every intelligent woman owes it to herself and her State to be in [a] position to vote on November 2,” one writer advised. The registration process, however, involved quite a bit of agency on the part of the newly enfranchised women. As all voters were required to do, they had to register in person in their own precincts, often having to “hunt up the registration officials.” Saturdays, it was noted, might be the best day to register, since women could likely find the registrar at his precinct then. Husbands and other male relatives were urged to accompany reluctant or timid women to the registrar. “Go to it, gentlemen” one local article admonished. To get women to register, the writer suggested, “Some of them apparently are going to need a lot of eloquent ‘persuasion’ of one sort and another.”  ("Democratic Speaking," Reidsville (NC) Review, October 22, 1920, 4.) ("Democratic Speaking," Reidsville (NC) Review, October 22, 1920, 4.) This public encouragement that white women received to register and vote in 1920 did not extend to African American women, however. As countless historians have documented, African Americans instead faced hostility, intimidation, and suppression of their votes across the Jim Crow South for much of the twentieth century. In North Carolina, an all-white political system had controlled the state since the amendment was passed in 1900 meant to disenfranchise black men. In order to maintain their dominance (and in the event that black women did manage to register and vote for their opposition), it was important to these leaders to secure the votes of newly enfranchised white women. Several appeals appeared in Rockingham County newspapers in the fall of 1920 specifically urging white women to register and then vote to keep the “whites-only” state and local governments in power. To expedite registration, some potential barriers to women’s participation in the coming election were removed. The yearly poll tax, which males had been paying to be eligible to vote, was suspended in 1920 for female voters. Women were assured that “no question will be asked as to the poll tax” when they went to register, as a special session of the NC legislature had eliminated the tax for them for one year only “because of the short time before [the] election and the difficulty in collecting from the women.” They were also assured that they would not be required to serve on juries as a result of registering. Women would not even have to reveal their ages in the registration and voting process, they were told, but needed only to state that they were 21 or over. There had been some pro-suffrage activity in the area, as a chapter of the Equal Suffrage League of North Carolina had been established in Reidsville by 1914, but many did not expect much enthusiasm for voting from females locally. “Whether a woman favored suffrage or not,” the Reidsville paper noted, “suffrage has come.” Antisuffragists claimed that “the majority of women of the county care but little about the ballot,” but large numbers apparently did register and vote in 1920. “Who says our women are not going to vote,” a Reidsville editor wrote, upon hearing that in another NC town, Greenville, women outnumbered men by 200 (1306 to 1100) at the conclusion of the 1920 voter registration window. Although it is not clear exactly how many Rockingham County women voters registered and cast ballots in 1920, there were 900 new names on the books in four Reidsville precincts alone and the total number of votes in the election—more than 9,000—was double the total cast four years earlier.  (Vice-Presidential candidate Calvin Coolidge/ Reidsville (NC) Review, October 26, 1920, 1.) (Vice-Presidential candidate Calvin Coolidge/ Reidsville (NC) Review, October 26, 1920, 1.) Campaigns in the fall of 1920 were vigorous, with both political parties trying to reach newly enfranchised voters. Candidates for Rockingham County Sheriff challenged one another on who would enforce the newly enacted Prohibition amendment most effectively. Candidates for at least a dozen offices appeared at events in communities across the county, with local school houses being popular meeting places. A list of speakers on behalf of Democratic candidates read, “Everybody Invited, especially the ladies.” Plenty of candidates came to Rockingham County to campaign. Republican candidate for Governor, John J. Parker, addressed a “large audience” at the courthouse in Wentworth (now home to the Museum and Archives of Rockingham County) and later that evening in Spray. The advertisement for his speech read, “Ladies Especially Invited.” On the Democratic side, two future governors—O. Max Gardner and Clyde Hoey—spoke on behalf of their party’s candidates. Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels gave a two-hour speech to more than two thousand at Pinnix’s Warehouse in Reidsville, where he described the efficient use of the navy in winning the “great war” and gave a defense of President Woodrow Wilson’s peace efforts. Even Vice-Presidential candidate Calvin Coolidge visited Rockingham County during the last week of the 1920 campaign. He and his party came to Reidsville on a special train, which stopped before a large crowd gathered at the station. Coolidge spoke from the platform, thanking them for their hearty welcome and expressing what he called his “real American message,” support for Americanism and Republicanism.  (Mrs. B. Frank Mebane of Spray, in a French uniform worn as she worked in devastated regions of post-war Europe/ Greensboro (NC) Daily News, October 29, 1920, 11.) (Mrs. B. Frank Mebane of Spray, in a French uniform worn as she worked in devastated regions of post-war Europe/ Greensboro (NC) Daily News, October 29, 1920, 11.) As the election neared, campaigns focused on whether to support the newly organized League of Nations. In an emotional appeal a few days before the vote, an editorial appeared in a county newspaper congratulating the “women of Reidsville” for registering, and urging them to vote Democratic on the basis of support for the organization meant to avoid future wars. Accusing the opposition of denouncing Woodrow Wilson and sneering at the “most sacred things,” the editorialist claimed, “Reidsville boys—sons of Reidsville mothers—‘lie sleeping in Flanders Fields.’” They had given the supreme sacrifice of their lives in a “victory that would end war in this world forever.” To ensure this peace, women must now vote to support the League of Nations. This view was bolstered in speeches by prominent citizen, Mrs. B. Frank Mebane, of Spray. Although known to have supported Republicans in previous elections, Mrs. Mebane spoke on behalf of Democratic candidates in 1920, based on her concern about avoiding another terrifying war. Having done relief work in areas of France devastated by the war and in the Balkans, she had seen first-hand “the full horror of war and the hideous suffering of the innocent.” Understanding this, Mrs. Mebane told audiences that the U.S. must join the League of Nations.  (“The Woman's Vote," political cartoon, Greensboro (NC) Daily News, October 25, 1920, 4.) (“The Woman's Vote," political cartoon, Greensboro (NC) Daily News, October 25, 1920, 4.) Many were unsure about how the more than twenty-five million American women would vote in their first general election. One political cartoon depicted this uncertainty as a sphinx-like figure, deliberating between the two political parties. In North Carolina, some political prognosticators anticipated about 75,000 women casting ballots in 1920. In preparation for the coming election, the state of North Carolina printed five million ballots, twenty-five percent more than in 1916. As was customary at that time, separate ballots for Democratic and Republican slates of candidates were printed, one million state and federal tickets for Democrats and 700,000 for Republicans, who were expected to number fewer at the polls based on the previous election cycle. Congressional ballots were printed separately by district on additional sheets of paper and county election boards were responsible for printing ballots for local races.  (Colonial Theater ad, Reidsville (NC) Review, November 2, 1920, 4.) (Colonial Theater ad, Reidsville (NC) Review, November 2, 1920, 4.) When voters checked in at the polling place, they picked up the ballots or the “tickets” they supported from different stacks and voted in a very public manner. Typically, there were no private polling booths; a measure to implement them was even defeated in the 1921 session of the General Assembly. In 1920, voters deposited their ballots in one of six different boxes, depending on whether the ticket was for a local, state, district, or national office. This process could be problematic, as an incident of voter intimidation reported in Governor Thomas Bickett’s home county of Franklin illustrates. There, ballots for a voter’s preferred party could be picked up at the opposite ends of a long table. Above the Republican end, it was alleged, a “huge live rat” was hung by their opponents to deter women voters from approaching and getting their ballots. Locally, women were encouraged to vote early on election day (by 10 a.m.) and to take part in the excitement of election night by coming to one of the local theaters to learn about the election results. The Colonial Theater advertised that “Ladies are especially invited to attend” the gathering there, where the complete returns of the election would be announced as soon as they were received. Along with a Paramount and Artcraft feature, the Grande Theatre also offered that evening, “full election returns of the county, State and nation without any extra charge.” In the presidential race, the Republican ticket of Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge won the White House. Rockingham County voters, however, chose their opponents, Democrats James M. Cox and his running mate, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, by a 902-vote margin. The entire Democratic ticket was elected in North Carolina state races as well as in all local offices. This prompted the Reidsville paper to issue a congratulatory piece, noting, “We knew old Rockingham’s women would do the proper thing.”  (Image of Harding and Coolidge, elected president and vice-president of the U.S. in 1920/ “The Victors,” Reidsville (NC) Review, November 5, 1920, 1.) (Image of Harding and Coolidge, elected president and vice-president of the U.S. in 1920/ “The Victors,” Reidsville (NC) Review, November 5, 1920, 1.) Having achieved its goal of enfranchisement for women, the North Carolina Equal Suffrage Association, the primary suffragist group in the state, morphed into a new organization, the League of Women Voters. In October 1920, this group met in Greensboro, with Gertrude Weil, perhaps “North Carolina’s best-known suffragist,” as its leader, and made plans to educate the women of the state in a bipartisan manner about “the duties involved in their new political freedom.” Women’s enfranchisement in 1920 did open doors for females in political roles. That fall, the first two women notaries public in Rockingham County were commissioned—Kathleen Walker of Spray and Laura Powell of Reidsville. In the 1920 election, Lillian Exum Clement of Buncombe County was elected the first female member of the NC General Assembly. Foreshadowing later women in educational leadership, Mary Settle Sharpe, the daughter of prominent Rockingham County judge Thomas Settle, Jr., ran for NC Superintendent of Public Instruction in 1920. Although she was not elected, Sharpe encouraged women from all across the state to vote and she received especially strong support from fellow faculty members and students at the North Carolina College for Women (now UNC Greensboro).

North Carolina was among the ten states that did not ratify the Nineteenth Amendment; nine of the ten were in the South, where women’s suffrage was often not well supported and anti-suffragist groups worked actively against the amendment. Some opponents saw the enfranchisement of women as being forced upon the South by the overreach of the federal government. In fact, women’s suffrage was not officially ratified in North Carolina until 1971. References: Articles in the Reidsville (NC) Review: “Rockingham County Has a Population of 44,149,” September 3, 1920, 1; “Printing Five Million Ballots,” September 7, 1920, 1; “Women Will Register Here for Election,” September 7, 1920, 1; “Township Population of Rockingham County,” September 7, 1920, 1; “Of Local Interest,” September 7, 1920, 5; “Campaign To Be Waged To Educate Women To Vote,” September 7, 1920, 1; “At Greenville, N.C.,” September 10, 1920, 1; “Of Local Interest,” September 17, 1920, 5; “Instructions Issued for Election Boards,” September 28, 1920, 10; “Women Must Register,” September 28, 1920, 3; “Of Local Interest,” September 28, 1920, 5; “Public Speaking, Hon. John J. Parker,” September 28, 1920, 10; “Candidate Parker Made Speech at Wentworth,” October 1, 1920, 1; “Information for Women Voters,” October 1, 1920, 1; “Secretary Daniels Comes on Friday,” October 1, 1920, 1; “Hear Hon. Josephus Daniels,” October 1, 1920, 7; “Two Thousand Heard Secretary of Navy,” October 5, 1920, 1; “Of Local Interest,” October 8, 1920, 5; “News of Reidsville and Rockingham,” October 12, 1920, 1;”Pointers for Qualifying To Vote in the Election To Be Held November 2nd—Registration Books Close 23rd October,” October 12, 1920, 1; “News of Reidsville and Rockingham,” October 15, 1920, 1; “Of Local Interest,” October 19, 1920, 5; “Democratic Speaking,” October 22, 1920, 4; “Gov. Calvin Coolidge,” October 22, 1920, 4; “The Vice-Presidential Candidate Spoke Here,” October 26, 1920, 1; “Of Local Interest,” October 26, 1920, 5; “The Women,” editorial, October 29, 1920, 10; “Hear Hon. O. Max Gardner,” and “Hear Hon. Clyde R. Hoey,” October 29, 1920, 8; “Gardner and Hoey Are in County for Speeches,” October 29, 1920; “Of Local Interest,” October 29, 1920, 5; “Colonial Theater ad,” November 2, 1920, 4; “Eleventh Hour Hopes,” November 2, 1920, 4; “To the Voters,” A. P. Sands, November 2, 1920, 4; “Heavy Democratic Majority in State,” November 5, 1920, 1; “Three Cheers for Rockingham!” November 5, 1920, 4; “The Winners,” November 5, 1920, 1; “County’s Vote,” November 5, 1920, 1; “Official Majorities in Rockingham County,” November 9, 1920,1; Articles in the Greensboro (NC) Daily News: “The Women Who Vote Must Meet the Same Sort of Test as Men,” October 7, 1920, 1; Women Voters of the State Meet Here and Perfect Organization,” October 8, 1920, 1; “Mrs. Sharpe Heard by Crowd at Siler City,” October 13, 1920, 3; “Democrats Think 75,000 Women Will Vote in Election November 2,” October 24, 1920, 7; “The Woman’s Vote,” political cartoon, October 25, 1920, 4; “Mrs. B. Frank Mebane, of Spray, Who Is Making Speeches for League of Nations,” October 28, 1920,11; Gilmers, Inc., advertisement, October 29, 1920, 8; “Democrats Claim To Have Captured State by Majority of 85,000,” November 3, 1920, 1; “Rockingham Democratic by a Majority of 975,” November 3, 1920, 1; Other sources: Margaret Supplee Smith and Emily Herring Wilson, North Carolina Women: Making History (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 203 “best-known suffragist” quotation, 215-218; 216 “Equal Suffrage League” chapter in Reidsville quotation; “Thomas Walter Bickett,” NCpedia, State Library of North Carolina, North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/bickett-thomas-walter; Caroline Pruden, “Women Suffrage,” NCpedia, 2006, https://www.ncpedia.org/women-suffrage; Meilan Solly, “What the First Women Voters Experienced When Registering for the 1920 Election,” Smithsonian Magazine, July 30, 2020, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/what-first-women-voters-experienced-when-registering-1920-election-180975435/; “She Changed the World: North Carolina Women Breaking Barriers,” online exhibit, North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, https://www.ncdcr.gov/about/featured-programs/she-changed-world-north-carolina-women-breaking-barriers; ”She Changed the World Educational Activity Guide,” North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, https://files.nc.gov/ncdcr/documents/files/She-Changed-the-World-Educational-Activity-Guide-.pdf; “Mary Settle Sharpe: Keen in Intelligence, Kindly at Heart, and Democratic in Sympathy,” Spartan Stories: Tales from the University Archives at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, http://uncghistory.blogspot.com/2018/11/mary-settle-sharpe-keen-in-intelligence.html.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Articles

All

AuthorsMr. History Author: Bob Carter, County Historian |

|

Rockingham County Historical Society Museum & Archives

1086 NC Hwy 65, Reidsville, NC 27320 P.O. Box 84, Wentworth, NC 27375 [email protected] 336-634-4949 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed