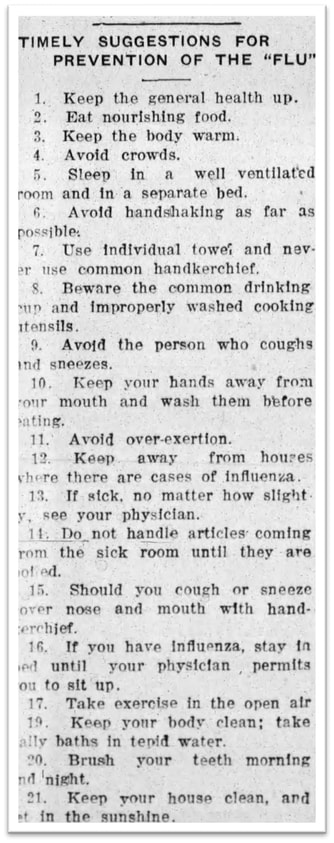

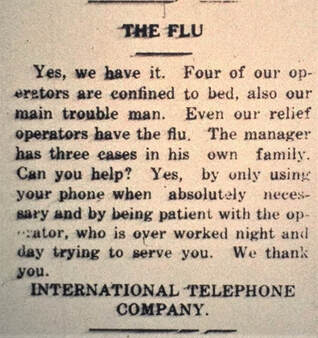

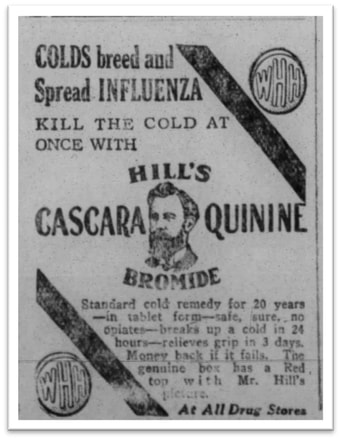

This Month In Rockingham County History: March - A Second Wave of Influenza Hits Rockingham County3/31/2021 Foreword by Debbie Russell: What we think of as the 1918 flu lingered into 1919, causing months of anxiety. Then, a second major outbreak of influenza made its way across Rockingham County in early 1920, bringing many of the same questions and dilemmas that COVID-19 has posed to us one hundred years later. March 1918 - 1920As the autumn of 1918 gave way to a new year, Rockingham County residents were hopeful that the worst of the fatal influenza epidemic was behind them. At its peak in North Carolina from October through December of 1918, the deadly influenza killed scores of area residents and led to the highest yearly death rate for the United States on record up to that time. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, over 32 percent of the total deaths in 1918 were due to influenza and pneumonia, the pandemic’s companion condition. In fact, according to a contemporary report, the 1918 flu accounted for nine times as many deaths among Americans as World War I. As they made their way forward into a postwar and post-pandemic world, dozens of local families continued to profoundly grieve the loss of their loved ones, both to war and disease. Without doubt, the 1918 influenza disrupted daily life, and, just as with COVID-19 in our time, local folks made adjustments, some quite severe, to weather the epidemic. Health officials ordered quarantines and public gatherings were forbidden. Schools and churches closed. Much anticipated events were cancelled. In the subsequent months and throughout the next year, the public worried about a recurrence of the deadly infection. Although the U.S. Surgeon General had assured Americans in December 1918 that the influenza was “gone for good,” local cases, especially in the rural areas, continued to flare up in the early months of 1919. Some tried to gird themselves against an influenza attack by following the advice of a Georgia doctor to sprinkle sulphur in their shoes worn as they moved about in the community. A Reidsville editor even noted that a large “sulfur club” had formed locally and that, to his knowledge, no member of the club had contracted the virus. Still, in the Summerfield area, residents reported in late February 1919 that the “influenza epidemic situation is bad yet,” and that a number of people there were “seriously ill with it.” Multiple members of the Gamble, Case, and Angle families were all confined to their homes with the illness. The influenza outbreak continued to be serious in nearby Caswell County as well. “Conditions seem to be growing worse rather than better,” one resident reported. The public also received news that Thomas Settle, III, a lawyer, former U.S. Congressman, and a member of a prominent Rockingham County family, had died in an Asheville hospital after suffering from influenza and pneumonia for several weeks. Although serious cases of the influenza extended into 1919, the NC General Assembly rejected calls that they suspend their session. The most vocal critics of this proposal even called the suggested closing of the legislature “unmanly” and insisted that representatives stay in Raleigh and do their duty.  (Reidsville Review, October 7, 1919, 1.) (Reidsville Review, October 7, 1919, 1.) Some areas of Rockingham County did, indeed, report that in early 1919 the flu had “about run its race.” Reports from Mt. Carmel and Stoneville happily noted that the epidemic seemed to be “on the decrease” and that the flu had “almost died down.” A Pelham resident reported in late February 1919 that no new cases had appeared in that area, that churches and the graded school were back open, and “our people can mingle again.” The county gradually reopened. Tickets for some cancelled events such as the Lyceum attractions in Reidsville had to be refunded in the aftermath of the epidemic’s first wave. Reidsville’s Grande Theater opened back up in early 1919, but in compliance with new health ordinance requiring more ventilation, and thus encouraged its patrons to come “more warmly clad” to their shows. A resident of the Narrow Gauge section even reported in late February that a large crowd had enjoyed a Thursday evening dance in their community and that dances were “all the go” in their neighborhood. By late spring, things seemed to be returning to normal. Public health officials and medical experts urged Congress to appropriate money to study the 1918 pandemic that had caused so much death, in an attempt to determine its cause and effective treatments. Health officers and doctors continued to remind citizens of ways to promote sanitation and prevent infectious diseases from spreading. Some warned of a recurrence, though likely less severe, in the fall of 1919. State health officials sent out an urgent request in mid-September 1919 to all county commissioners that they take steps to combat the infection should it reoccur. The Rockingham County commissioners received a letter asking that they “AT ONCE” gather all the public welfare agencies and organize supervisors in every township in the county to prepare for a possible outbreak. These men and women in each community would stay alert to the situation in their own areas, keep the county and state informed, and assist their neighbors. “In the late epidemic of influenza [1918], whole families were stricken so that no member of the family was able to get out and ask for aid,” the head of the State Board of Health wrote. “We do not want this to happen again in North Carolina.” As the winter months approached a year after the initial outbreak, the public was naturally anxious about a resurgence of the virulent disease. As feared, in September, a growing number of cases were reported in some areas of North Carolina, including several in Charlotte and in Greensboro. Several hundred cases in fourteen states were reported by early October, but symptoms appeared milder than those of the previous year. The numbers never reached epidemic proportions in most areas in the fall of 1919. Many were no doubt comforted by the report that only 7,000 cases of influenza had been reported throughout the U.S. from September 1919 to January of 1920, compared to the 400,000 reported during the same time the previous year. Many of the 1919 cases also appeared less virulent. Scholar John M. Barry’s research in The Great Influenza has confirmed that, just as with the COVID-19 virus, many variants of the 1918 influenza developed worldwide and, for a number of reasons, were less deadly in many populations. In early 1920, however, the influenza epidemic strongly reemerged, first in military camps and among American troops in Germany. By the end of January, influenza had reappeared in twenty states. In the North Carolina mountains, Buncombe County closed all theatres, schools and churches and, to stem the spread of disease, “public gatherings of any kind” were forbidden. More than 6,000 cases were reported in Chicago, 1,200 in only one day. In New York, the number of infections approached epidemic proportions in late January 1920, and about a month later, there were so many deaths among the inmates of one almshouse and hospital that burial facilities were “exhausted,” and bodies in coffins waited outside on the ground. By the first week of February 1920, the names of numerous influenza patients were again being listed in Rockingham County newspapers. “The influenza situation is beginning to be very serious around here,” wrote a resident of Route 5, Reidsville. J. H. Williams of Route 4 similarly reported that there were a large number of cases in his section. Multiple members of many families were listed. In Reidsville, three Pinnix children as well as three in the Glidewell family were confined to home by the flu in early February. Dr. J. B. Ray of Leaksville reported twelve cases on February 4. The Reidsville paper noted that the “Sulphur Club” had been revived there, with the slogan “put sulphur in your shoes and thus ward off the flu.” The local situation grew even worse. “The epidemic is spreading like wildfire in the county and State,” the Reidsville Review reported in mid-February, listing a dozen local cases as evidence to add to the nearly one hundred they had earlier noted. The Tri-City Daily Gazette similarly recorded the epidemic in the communities of Leaksville, Spray and Draper. Several dozen influenza patients were named in the columns of that publication during February and March 1920. The Gazette editor estimated the number afflicted in his area to be in the hundreds. “The mills are beginning to feel the effect,” he wrote, “as one after the other goes home sick.” Cases of influenza became so widespread that a reader, called the “town poet,” suggested that the Review’s slogan be changed from “Covers Rockingham Like the Morning Dew” to “Covers Rockingham County Like the Flu.”  (Tri-City Daily Gazette, February 14, 1920, 4.) (Tri-City Daily Gazette, February 14, 1920, 4.) Entire workplaces were affected. The county sheriff announced that the February term of court had been discontinued because of the influenza outbreak. Six members of Reidsville Post Office staff were out of work with the flu. “The few who are left,” an announcement read, “asks the public to bear with them as they are doing the best they can.” Almost all the staff of the Tri-City Daily Gazette were down with the flu, including several of the carrier boys. “The Gazette force is badly crippled” by the infection, the paper reported. During the sickness, the wife of one of the staff members and a teenage boy worked together to produce the paper for eight consecutive days. In the Leaksville area, the telephone company work force was so severely hampered by the influenza epidemic that they even asked customers to use their phones only when “absolutely necessary.” When this resurgence of influenza hit North Carolina and Rockingham County in February 1920, the experience of 1918 restrictions was something many wanted to avoid. Some national health experts told the public that medical professionals had learned from the 1918 experience and were able to control the germs. Others offered the advice that simpler remedies such as sunshine could be effective in preventing infection. Another health official advised, “Don’t shake hands, salute,” in order to avoid contaminating contact. A variety of pharmacy products again offered themselves as vehicles to better health and resistance to the flu. As they had during the fall of 1918, familiar treatments such as Vick’s VapoRub and Hill’s Cascara Quinine again altered their advertisements to appeal to those threatened by influenza. “Don’t wait until your cold develops Spanish Influenza or pneumonia,” one ad warned. Interestingly, just a month after the start of national Prohibition, some were suggesting whiskey as a treatment for the virus, but both the Anti-Saloon League and the NC Board of Health were noted in the local newspaper as being opposed to this “medicinal” use.  (Reidsville Review, January 27, 1920, 4.) (Reidsville Review, January 27, 1920, 4.) In February 1920, once again, Rockingham County officials had to make decisions about quarantining and shutting down public gatherings. Faced with hundreds of cases, a “rigid’ quarantine was imposed for most of the month by Reidsville health commissioners. Because of reports that “about every other house in town has one or more patients,” schools were closed and all public gatherings were banned, except church services, which were left to individual congregations. Local ministers, however, voluntarily agreed to stop services. Whether to close the schools was the most debated issue in the influenza resurgence. Many likely recalled the difficulty of making up hours for missed school days after the 1918 outbreak. Then, some teachers had refused to work on Saturdays to make up learning time, and three high school teachers had even resigned rather than do so. One and two-teacher rural schools (the majority of those in the county) were dependent, of course, on the good health of their teachers and many had already closed as influenza hit their instructors. One teacher at Mt. Carmel school, Miss Elizabeth Gerrey, was called home to Stoneville to “the bedside of her people” who were sick with the flu. Another, Miss Mollie Alcorn, closed her school at Salem until the flu subsided. Student absences in February 1920 were mounting, with one Reidsville class having only twelve of its forty students present. However, one influential educator, Principal P. W. Gwynn, spoke against closing the schools. He argued in a lengthy piece in the Gazette that the schools and churches were too hastily closed when what should be done during an epidemic was to train more nurses and helpers and carry on. Besides, Gwynn asserted, school closings seriously disrupted learning and would mean an illiterate North Carolina if continued. When schools were closed, the children paid “little or no attention to the order to stay home” and merely used the time to play with their friends, he wrote. To get the community through this second wave of the influenza, volunteers helped their neighbors. One farmer from near Lawsonville came into Reidsville to get some medicine for his neighbors whose “entire households were entirely afflicted,” and then walked the seven miles back home “on one of the coldest nights of the winter” to deliver it. The Red Cross established a kitchen in Mitchell’s boarding house at the corner of Main and Gilmer streets in Reidsville to prepare food for those recovering from the flu. Despite a call from Governor Thomas Bickett for more nurses to leave private care and provide service to the broader public, there was a scarcity of trained nurses in Rockingham County. Both men and women volunteered locally to assist patients through the Red Cross, some working at the Emergency Hospital in Reidsville set up at the W. C. Harris home on Main Street. Possibly the most pitiful local story of the 1920 epidemic was that of the six orphans, ages 7, 9, 10, 12, 14, and 16, who, since the deaths of their parents more than a year earlier, had been living on their own on a farm about seven miles from town. When five of the children contracted serious cases of the influenza, neighbors offered $5.00 a day to someone who could care for them but could find no one. The younger four siblings and the fourteen-year-old, who died from the virus a day later, were brought into Reidsville for emergency care. Red Cross volunteers nursed the four children, all boys, through the infection and sought clothing donations for them from the public. The county welfare department was eventually able to place two of the boys with area families. The other two returned to the farm to “finish the crop they had started.” As March 1920 unfolded, influenza cases were still reported, while churches reopened and students returned to school. Schools in Stoneville reported two-thirds of students in attendance in the first week of the month, while the attendance in the Madison schools “was not up to standard.” Rockingham County residents, like all those affected by the influenza outbreak, found themselves in a “perplexing situation.” The dilemma faced by the public was, as one observer wrote, “One day the situation is greatly improved and during the night scores of new cases spring from every direction.” As the county emerged from the second wave of the epidemic, the Ministerial Association of Leaksville-Spray-Draper no doubt spoke for many others in their resolution of March 22. In gratitude, they recognized the front-line workers—the health officials, doctors, and nurses—who had helped their neighbors through the recent influenza epidemic, a virus that for a second time had “greatly endangered the lives and health of many people in our community.” References:

John M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History (New York: Viking, The Penguin Group, 2004), 356- 391; Articles from the Tri-City Daily Gazette: “Epidemic of Influenza in Northern Sections Including Chicago,” January 19, 1920, 1; “Tanlac Ad,” February 4, 1920, 4; “Local News,” February 3, 1920, 4; February 5, 1920, 4; February 11, 1920, 4; February 12, 1920, 4; February 18, 1920, 4; February 28, 1920, 4; March 2, 1920, 4;; “The Flu,” February 14, 1920, 4; “The ‘Flu’ Has Struck Us,” February 17, 1920, 2; “Three Men of Gazette Force Are Ill with Influenza,” February 18, 1920, 4; “Explanation,” February 19, 1920, 2; “Disabled but Functioning,” February 20, 1920, 2; “Editorial,” February 26, 1920, 2; P. H. Gwynn, “A Generation of Cowards,” February 13, 1920, 1; “Governor Bickett Sends Call for Trained Nurses,” February 14, 1920, 1; “Ministerial Association Thanks Health Officers,” March 23, 1920, 4; Articles from the Reidsville Review: “Review of the Town and County News,” December 13, 1918, 8; February 21, 1919, 5; December 31, 1918, 8; January 3, 1919, 8; “The News in Brief Since Our Last Issue,” September 19, 1919, 1; October 2, 1919, 3; January 23, 1920, 1; January 27, 1920, 1; January 30, 1920, 1; “City Local News in a Condensed Form,” December 20, 1918, 1; December 31, 1918, 5; “Of Local Interest,” February 3, 1920, 5; February 6, 1920, 5; February 10, 1920, 5; February 13, 1920, 5; February 17, 1920, 5; February 24, 1920, 5; February 27, 1920, 5; March 9, 1920, 5; “Caught Just Before Going to Press, January 23, 1920, 1; March 2, 1920, 1; “The Highest Death Rate in History in 1918,” February 6, 1920,7; “Interments at Greenview,” January 10, 1919, 1; “Saturday School Has Been Abolished Here,” February 11, 1919, 1; “A Modern Example of a Mediaeval Plague,” February 21, 1919, 4; “Thomas Settle, Native of This County, Died Monday,” January 24, 1919, 5; “Pelham,” February 28, 1919, 7; “Mt. Carmel,” January 3, 1919, 3; “Stoneville,” February 7, 1919, 5; “Lyceum Money Will Be Refunded,” January 17, 1919, 1; “The Flu and the Scare,” January 17, 1919, 4; “News of Reidsville and Rockingham,” January 24, 1919, 5; “Narrow Gauge (Route 6),” February 28, 1919, 7; “Predicts Another ‘Flu’ Epidemic Next Winter,” March 7, 1919, 1; “Timely Suggestions for Prevention of the ‘Flu’,” October 7, 1919, 1; “Some Flavors of Tar, Pitch, Turpentine,” September 23, 1919, 1; January 30, 1920, 1; February 10, 1920; February 20, 1920, 6; “Flu Epidemic This Year?” September 5, 1919, 11; “Don’t Shake Hands, Salute,” February 3, 1920,1; “To Prevent Flu and Colds,” Vick’s VapoRub Ad, February 10, 1920; February 24, 1920, 3; “Whiskey in Influenza Treatment,” February 13, 1920, 3; “Rigid Quarantine Ordered in Reidsville,” February 6, 1920, 1; “Thought Peak Has Been Reached Here,” February 10, 1920, 1; “Sunshine is a Relief to ‘Flu’ Sufferers,” February 17, 1920, 1; “Emergency Hospital May Be Opened Here,” February 13, 1920, 1; “Mt. Carmel,” February 20, 1920, 4; “Greenwood,” February 20, 1920, 4; February 27, 1920, 7; “Appeal for Clothing for Four Orphan Boys,” February 24, 1920, 1; “Happy Home,” February 27, 1920, 7; “Quarantine Has Been Lifted in Reidsville,” February 24, 1920, 1; “With Our Subscribers,” January 16, 1920, 1; February 3, 1920, 1; “Route 5,” February 6, 1920, 5; “Stoneville,” February 27, 1920, 7; “Ruffin,” February 27, 1920, 7; “Route 1,” March 2, 1920, 7; “Madison,” March 2, 1920, 7; March 9, 1920, 5; “Route 4,” March 2, 1920, 4; “Praise for Red Cross from Headquarters,” March 2, 1920; “Old Stoneville Has Taken on New Life,” March 5, 1920, 1.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Articles

All

AuthorsMr. History Author: Bob Carter, County Historian |

|

Rockingham County Historical Society Museum & Archives

1086 NC Hwy 65, Reidsville, NC 27320 P.O. Box 84, Wentworth, NC 27375 [email protected] 336-634-4949 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed