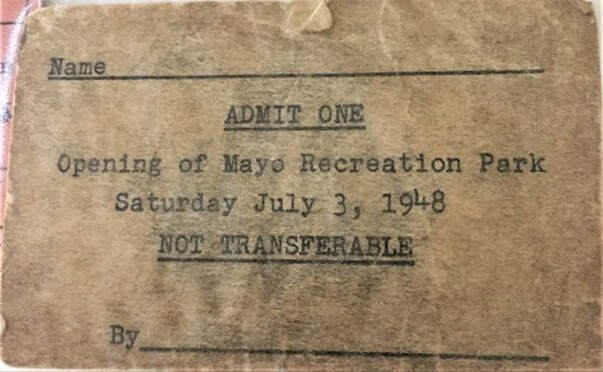

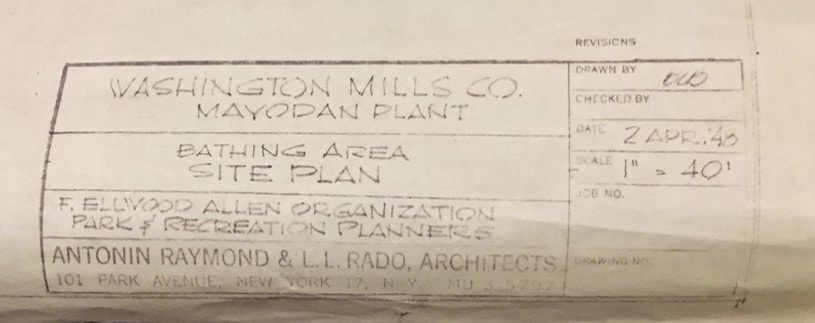

July 1948 (Above: Admission ticket for the dedication of Mayo Park in July 1948. Only those with these special tickets were allowed to attend the festivities. Courtesy Connie Fox, Scrapbook, ticket donated by Gloria Steele to the Mayo River State Park Archives) (Above: Admission ticket for the dedication of Mayo Park in July 1948. Only those with these special tickets were allowed to attend the festivities. Courtesy Connie Fox, Scrapbook, ticket donated by Gloria Steele to the Mayo River State Park Archives) In July 1948, the Washington Mills Company opened a new and exciting recreational facility for its employees and their families—Mayo Park, often called Mayo Lake by locals. Situated about two miles north of Mayodan, the park offered serene, wooded areas and trails, a large picnic pavilion, a playground, fishing, and the highlight of the facilities: a bathhouse, a sandy “beach,” and a lake for swimming and diving. Special invitations and admission tickets were required when a crowd estimated to number about three thousand gathered for the July 3, 1948, event dedicating the park. The President of Washington Mills, Agnew Bahnson, gave the keynote speech, explaining that the mill was partnering with the Mayodan Y.M.C.A. to provide “plenty of fresh air, sunshine, camping, family picnic areas, nature trails, games, swimming, and other forms of recreation” for the company’s employees, their relatives, and other citizens of the community, where the Mayodan mill had been located since the 1890s. Other officials of the company, including W.H. Bollin, General Manager of the Mayodan plant, and R. A. Spaugh, company vice-president, were present to show their support, as was Mayodan mayor A. G. Farris. In fact, the park opening was considered important enough to postpone the very popular Bi-State League baseball game originally scheduled for that day in Mayodan. Plans for the 400-acre park and facilities, a “company gift to the community,” were drawn up in the spring of 1948, and in only a matter of months, the park was ready for use. In addition to the speeches by dignitaries, the opening day’s celebration included a diving exhibition from the platform at the newly created lake, an afternoon of swimming, and a hearty barbecue lunch, deemed “the best free food he had ever gotten anywhere” by local photographer Pete Comer who was on hand with his camera to record the event. The main attractions at Mayo Lake for youngsters who grew up going there during the 1950s and 1960s were the summer swimming facilities. Use of the lake for swimming and diving required employee and family identification, YMCA membership cards, or other permits. Bus transportation from the Y in Mayodan to Mayo Lake, on a vehicle they called the “Gray Goose,” enabled many youths to come for swimming. When they checked in at the bathhouse, for a fee of ten cents, they were issued a metal basket to hold their street clothes and given a large number pin to wear on their swimsuits. By the mid-1950s, Mayo Park gradually became the meeting place for many area organizations. Sunday and Wednesday evening vespers were well attended and involved an array of local churches and choirs. Scouting events of all kinds were held at the park. Aquatic life-saving instruction for teenagers was offered at Mayo Lake, leading to certification by the Red Cross. Summer day camps were held, with different weeks for younger boys and girls, and each fall a “Science Camp,” taught by students and staff from UNC Greensboro, was organized for western Rockingham fifth graders. During its heyday, Mayo Park had a parking lot for 400 cars. Many employee gatherings were also held at the large pavilion.  (Above: The Pavilion at Mayo Park was featured on the cover of a Japanese architecture publication from the 1960s. Architecture, a Monthly Journal for Architects and Designers, April 1962, Archival collection of Mayo River State Park) (Above: The Pavilion at Mayo Park was featured on the cover of a Japanese architecture publication from the 1960s. Architecture, a Monthly Journal for Architects and Designers, April 1962, Archival collection of Mayo River State Park) One of the most significant aspects of the original Mayo Park was its architecture. Washington Mills contracted with the firm of Raymond and Rado in New York to plan the park. Its structures were designed by Antonin Raymond, an associate of renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Raymond, a Czech designer, had worked with Wright in Japan on several projects in the 1920s and 1930s and the designs of the Mayo Park structures reflect both Japanese lines and Wright’s influence. Raymond explained the importance of blending architecture with natural settings in his plans for the park: “The idea behind the design of the buildings was to keep …[them] in harmony with the surroundings, by using natural materials, unpainted and unvarnished.” The Pavilion at Mayo Park was built according to these standards. The columns and rafters were made of hickory, the main roof was covered with cedar shingles, and the huge pavilion fireplace was constructed of local stone. It is thought that the steep pitch of the pavilion’s roof prevented the serious decay that caused the original bathhouse to be demolished. Another popular attraction of the park was a T-33A aircraft donated for display by the U.S. Air Force in 1965. Over the time it was at Mayo Park, the aircraft was enjoyed by the public and carefully maintained. As Mayodan Town Manager Jerry Carlton reported to military officials in 1976, “Our children and grownups alike have spent many pleasurable hours examining the plane and they continue to enjoy making those imaginary flights.” The aircraft was exhibited on the park grounds until it was returned to the Marines at Cherry Point, NC, in 1979. In creating the recreational setting at Mayo Lake for its employees, Washington Mills was continuing the practice of employers engaging in the daily lives of their workers, not only on the job, but also outside the workplace. Textile mills such as those in Rockingham County set up company stores and provided housing for their labor force, as well as offering other organized services and activities for their employees. In the early 1900s, for example, Spray Cotton Mill opened a day nursery in its factory for workers’ young children. In Like a Family, a comprehensive look at the lives of Southern cotton mill village workers, historians noted an array of mill-sponsored activities beyond work hours that included exercise sessions, baseball teams, sewing and cooking classes, and even brass bands, such as the 1920s Mayo Mills Band. These structured recreational activities were especially prevalent in the early twentieth century, but by midcentury were generally becoming fewer in number. In a 1950s promotional publication, however, Washington Mills boasted of its many offerings for its workforce: “These People Make the Product and they enjoy themselves in their leisure hours in many and varied forms of recreational facilities provided them by Washington Mills.” The brochure included photographs of participants in bowling and ping pong at the YMCA located adjacent to the Mayodan mill, as well as scenes from the Mayodan baseball field on Main Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, and the pavilion and swimming facility at Mayo Park. After the swimming facilities were closed in the 1960s, community residents continued to meet at Mayo Park for picnics and other gatherings through the mid-1970s. The area afterward fell into disuse, however, and for about thirty years was closed to the public, until it became a part of the Mayo River State Park. In 2005, the state of North Carolina allocated more than a million dollars to preserve the park’s structures and hire staff. Historian Dr. Lindley S. Butler served as chairperson of the Mayo River State Park Committee and several other Rockingham County Historical Society members were also instrumental in the preservation of the original Mayo Park structures, including Bob Carter and Charlie Rodenbough. To many citizens of western Rockingham County, Mayo Park was a much appreciated recreational destination from its opening in 1948 through the 1970s. Connie Fox, of Mayodan, may have the longest association with the Mayo Park area. She has worked at the office of the Mayo River State Park since its opening, just steps from Mayo Lake and the site where the original Mayo Park bathhouse once stood. (The original home of the park caretaker is now the state park office.) In fact, Fox, whose mother worked in the personnel office of Washington Mills, began her many visits to Mayo Park at the age of eighteen months and has many fond memories of playing on the wooden swings at the playground there as a child. “It was the best thing that ever happened to Mayodan,” she said. References

Jacqueline Dowd Hall, James Leloudis, et. al., Like a Family: The Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 1987), 126-139, (factory nursery, 134); Architectural Plans for Mayo Park and “Story of Washington Mills: Manufacturers of Mayo Spruce,” [mid 1950s?], Mayo-Washington-Tultex Mills Collection, 06-067, Rockingham County Historical Collections, Gerald B. James Library, Rockingham Community College, Wentworth, North Carolina, https://www.rockinghamcc.edu/library/findingaids/mayowashingtontultex.pdf; Interview of Connie Fox by author, July 12, 2021, Mayo River State Park, Mayodan, NC; Letters to and from U.S. Air Force to Town of Mayodan, May 26, 1976 and November 28, 1979, Scrapbook, Mayo River State Park; Antonin Raymond quoted in Architectural Record, 114, Scrapbook, Mayo River State Park; Reflections of Western Rockingham County, The Messenger, Randy Case and Deeanna Biggs, eds., (Marceline, MO: D-Books Publishing, 1993), 52, 56, 58, 71, 74, 89; Carla Bagley, “State To Save Park’s Historic Buildings,” Greensboro (NC) News & Record, December 7, 2005, B1, B2; Taft Wireback, “Mayo River: Park Gaining Momentum,” Greensboro (NC) News & Record, July 28, 2007, https://greensboro.com/news/mayo-river-park-gaining-momentum/article_51ad701a-e4fb-5d7c-a69b-6c1c4fca0b21.html; Articles from The Messenger, Madison, NC: “Formal Opening Ceremonies for Mayo Park Set for July Third,” June 17, 1948, 1; “Mayodan Game for Saturday Will Be Postponed,” July 1, 1948, 1; “Mayo Park Opening and Dedication Set for July 3,” July 1, 1948, 1; “Gala Throng Attends Mayo Park Dedication: Several Thousands Eat Barbecue and Enjoy Refreshing Swim,” July 8, 1948, 1; “Mayo Lake Will Open June 1,” May 19, 1955, 1; “Vespers at Mayo Lake Sunday,” June 9, 1955, 1; “Lifesaving Classes at Mayo Lake,” June 30, 1955, 1; Steve Lawson, “Architectural History in Our Own Back Yard,” May 13, 2005, 1, 6; Washington Mills Office Employees Photo Identifications: Front: Norris Griffin, Dr. T. B. Clay, Ben Archer, Bobbie James, Jane Pyrtle, Doris James, Violet Ledbetter, Margaret Tucker, R. B. Reid; Middle: unknown, unknown, Betty Jane Barrow, Emma Newman, Hazel Case, Ruby Lemons, Gladys Lundeen, Dot Ledbetter, Harvey Price, Rob Grogan, Red Drake/ Back: Virginia Payne, unknown, unknown, Peggy Myers, Clyde Johnson, Jane Richardson, unknown, Mildred Powers, Gretchen Sands, Ersell Minton, Otis Carter; Mayo Mills Band Identifications: Back L-R: Jesse Richardson, Jimmy Baker, Ross Myers, Kirby Reid, Frank Tulloch, Cecil Richardson, John Webb/ Front L-R: Sam Jones, Harold Myers, and Thomas W. Lehman, leader of band organized in 1915.

1 Comment

Charles Rodenbough

7/31/2022 11:22:33 am

This is a great record, Debbie. I wish you had included the important social/industrial impact that desegregation had on Mayo Park and Rockingham County. Mayo Park was closed by Washington Mills when African Americans sought use of the facilities. I think we need to include such an important 20th century influence on life in the county. It is part of the transition to who we are today.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Articles

All

AuthorsMr. History Author: Bob Carter, County Historian |

|

Rockingham County Historical Society Museum & Archives

1086 NC Hwy 65, Reidsville, NC 27320 P.O. Box 84, Wentworth, NC 27375 [email protected] 336-634-4949 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed