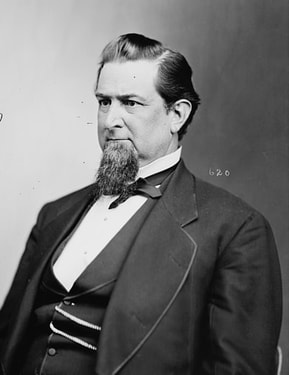

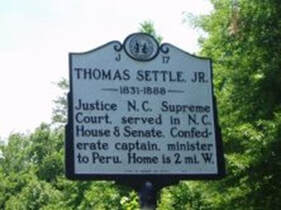

This Month in Rockingham County History: June - 'Thomas Settle, Jr. Makes His Spring Garden Speech'6/22/2021 June 1867 (Above: A portrait of Thomas Settle, Jr.: circa. 1865-1880: Library of Congress) (Above: A portrait of Thomas Settle, Jr.: circa. 1865-1880: Library of Congress) One of the most remarkable speeches ever made in North Carolina was given in Rockingham County in June 1867. The words came from one of the most prominent leaders of the era-- Judge Thomas Settle, Jr., who lived on the “river road” in the center of the county in a plantation house called “Mulberry Island.” Settle, who had himself been a slaveholder and served about a year in the Confederate military, emerged after the war as a primary voice for acceptance of Union victory and new roles for black citizens in postwar society. In what has become known as the “Spring Garden speech,” he sought to explain his views and guide his neighbors during one of the most troubled, as well as promising, times in our history—the years just after the Civil War. It was a time of deep divisions, burdens, devastation, and economic and political uncertainty, but also a moment when emancipation, new racial dynamics, and opportunities offered hope for renewal. Settle spoke to a biracial group of “neighbors and friends” gathered near his home, likely at the site of a former muster area that is today on the south side of Highway 135 between Mayodan and Shiloh. Here, Settle set forth the circumstances facing the South as he saw them and offered practical ways forward. “This is a novel scene in Rockingham,” Settle began. “You who were lately slaves, and you, who but lately owned them, are here today equals before the law” and should work together. There was nothing he would argue to one race that he would not say to the other. “Your rights and duties are mutual,” Settle declared, “and the sooner you understand them, the better for both.” Settle spoke to the economic realities facing his Rockingham County neighbors, both black and white. To the freedmen, he told them that he realized, “You want land and you want it cheap.” It could be had readily, he explained, for “a large majority of whites . . . are sinking under the weight of indebtedness,” and “property of every description will soon be for sale.” “Then save your money and buy land,” he suggested. No doubt surprising all, he urged his neighbors to stop denouncing the Yankees. “I tell you,” Settle said, “Yankee notions are just what we want in this country.” The North, “covered . . . with railroads and canals,” had flourished since it “had the good sense” to get rid of slavery. Some of their “educated labor and machinery,” as well as their investment in industry, were exactly what the South needed. The most practical, and ethical, path to take, urged Settle, would be to comply with Congressional mandates, rejoin the Union as quickly as possible, and work with the newly established Republican Party in the state, who were “trying to pull down none, but to elevate all.” We want to be “a party of principle,” he told the crowd. Settle outlined several goals for North Carolina in the Spring Garden speech. “There is no reason why the two races should be at enmity,” Settle asserted, “but many good reasons why they should be friends; our common interest demands it.” He continued, “My advice to the white man is to be kind and just to the colored man, make fair and liberal contracts with him, . . . and it is precisely the same to the colored man.” It would be “madness and folly” to oppose the Congressional reconstruction plans, he argued. Besides, he concluded, “the white and colored man ought to rejoice together, for they are both greatly benefited” by the end of slavery. An advertisement for the North Carolina Standard, an “unmistakably loyal” newspaper allied with Governor William W. Holden, probably stated the views of Settle and the state’s postwar leaders most aptly: They were “in favor of the RESTORATION OF THE UNION” and wanted a “loyal civil government which … [would] protect the lives and property of all, and do justice to all.” Some of Settle’s ideas in the Spring Garden speech about bringing together black and white men seemed to happen for a very brief time during Congressional Reconstruction, for no more than about three years, as African Americans participated in the politics of the area. With the advent of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, black males played a significant role in Rockingham County politics. In 1869, the voter rolls in Rockingham County listed 1,405 whites and 1,349 blacks. African Americans were represented on the first postbellum Board of Rockingham County Commissioners, when black teacher Robert Gwynn served alongside four white men, who had been elected by a vote of the people, as directed by the new 1868 North Carolina Constitution, rather than being appointed by the legislature. Six other NC counties also elected a black member to their county governing boards in 1868, and the City of Wilmington elected four African Americans to its eight-member council. Gwynn also later helped establish a school in District 30 near present-day Shiloh airport, adjoining land he had purchased from Thomas Settle in that area. The other members who served with Robert Gwynn in Rockingham County were William F. Windsor, John H. French, Charles Williams, and Zach Groom, chairman. These five, however, served only one term, 1868-1870, when state government was led by reformers. For the brief time reformers directed the state government, however, they produced a quite progressive state constitution and had a positive effect in determining the trajectory of the state for the next three decades. Representing Rockingham County at this constitutional convention were Henry Barnes and John French. Settle did not participate in the writing of this document, but his fellow judge Albion W. Tourgée, with whom he worked closely during these years, was one of the two representatives from Guilford County and was extremely active in crafting and influencing large portions of the new constitution. In his 1867 speech, Settle expressed the foundation of some of these plans for improvement in North Carolina. “I tell you frankly,” he said, “we must make up our minds to look at several things in a different light from that in which we have been in the habit of viewing them.” Especially regarding education, he argued, “We must bury a thousand fathoms deep all those ideas and feelings that prompted those cruel laws” against teaching African Americans. He urged, “Let school houses dot our hills at convenient distances from all.” Article IX of the 1868 North Carolina Constitution was the means of instituting this educational change. It mandated that counties be divided into school districts with school houses built in each district, providing a free and uniform education for all children of all races, ages six to twenty-one. Because they gave such serious effort to reviving public schools, the area of greatest long-term Reconstruction Republican influence may have been in education. What followed the stirring, yet practical, words of Settle’s Spring Garden speech and reforms at the state level was a backlash by the Ku Klux Klan. Circumstances became increasingly contentious and dangerous locally. In May 1869, there were reports that beatings of blacks had been going on for at least a month. There were at least sixty-two of these “outrages” recorded by the court clerk in Rockingham County. Nearby counties saw even more numerous serious racial attacks against blacks and their white supporters, including those resulting in the murders of black leader Wyatt Outlaw in Alamance and white Republican state senator John Walter Stephens in Caswell. As a judge, Settle was painfully aware of this violence as he handled many of these cases, tried to stop the attacks by charging the suspects with crimes, and even later testified before Congress about the violence. In this attempt to protect black citizens and bring the Klansmen to trial, he worked with Judge Albion W. Tourgée of Guilford County, the noted jurist and author. In mid-1869, Settle wrote to Tourgée that since the last court session in Rockingham, “Men in disguise, at night, . . . [had] inflicted cruel whippings upon several of our colored citizens.” The violence was “simply intolerable,” Settle wrote, and must be stopped. Both judges were threatened with violence themselves. Tourgée’s awareness of the danger was keen. “I have very little doubt that I shall be one of the next victims,” he wrote.  (Above: Cover of 1879 novel by Albion Tourgée based on his Reconstruction experiences in North Carolina) (Above: Cover of 1879 novel by Albion Tourgée based on his Reconstruction experiences in North Carolina) Later, Tourgée referenced many of these tense moments dealing with the Klan in his novels based on his experiences in North Carolina during Reconstruction. In A Fool’s Errand, by One of the Fools [1879], the judge dedicated an entire chapter to an incident of threatened Klan violence against his characters, Colonel Servosse and Judge Denton, thinly disguised versions of himself and Settle. In this book, “Rockford County” seems clearly to be Rockingham County and “Glenville” the substitute for Reidsville. As described in the novel’s Chapter XXXVI, “A Race Against Time,” Settle did, indeed, live on a “river-road” in between Madison and Wentworth, just a few miles from the train stop in Reidsville. What led to the sudden appointment of Thomas Settle, Jr. as U.S. ambassador to Peru in 1871 in the midst of these threats is better understood through the correspondence of the two judges. The continued threats of violence, not only against area blacks, but personally against Settle and Tourgée as well, took a toll on the judges and their families, so much so that both began to consider how they might remove themselves from the danger. They corresponded in the summer of 1869 about the increasing danger they sensed as charges were being prepared against the Klansmen. Tourgée wrote that since calling the Grand Jury, he had been “looking around ever since” in fear. They wrote Governor Holden asking for help. The following year Settle commiserated with Tourgée about the threats they both had suffered and praised his colleague and friend for trying to stop the Klan. “You have stood up like a hero,” Settle wrote, but said that he understood if Tourgée wanted to “be removed temporarily, at least, from the incessant persecution.” Ultimately, Tourgée looked abroad for a haven and shared his thoughts with Settle. He mentioned in a letter marked “Private and Confidential” that he contemplated getting an appointment to a consulate somewhere for “a year or two,” preferably in South America because he was “proficient in Spanish.” This plan likely became more urgent after one of Tourgee’s letters, full of details about the violence and asking for federal intervention, was printed without his permission in the New York Tribune. In September 1870, Tourgée informed Settle that he sought a specific position, one vacant in the “Chilian mission,” and that he desired “to leave the State for a time.” Not long after, however, it was Settle, not Tourgée, who obtained an ambassadorship—to Peru instead of Chile—and clearly for the same reason—to escape the dangers of KKK persecution. Both Settle’s daughter and wife wrote him during his one-year stay in Peru, suggesting that because of his role in supporting African Americans in court, threats still lingered against him and his family. Daughter Nettie wrote her father describing a frightening incident involving a newly hired hand, Luther Low, who was stopped by “some men camping at the bridge” and peppered with questions about Judge Settle’s whereabouts. Wife Mary wrote that she hoped this move to Peru was “all for the best” and that she would not wish him home “in all this strife for anything.”  (Above: Historic highway marker on Settle Bridge Road in central Rockingham County noting some of Thomas Settle, Jr.’s leadership positions) (Above: Historic highway marker on Settle Bridge Road in central Rockingham County noting some of Thomas Settle, Jr.’s leadership positions) Settle did come home to North Carolina after about a year in Peru. Upon his return, Settle remained active in the Republican Party, presiding at the 1872 national convention and running a close campaign for governor against Zebulon B. Vance in 1876. He then spent the rest of his career as a federal judge in Florida, though he maintained a family home in Greensboro. At his death in 1888, Settle was remembered in a local newspaper as one who might have continued his work “in allaying the bitterness of sectional and partisan animosities” and was called “probably the foremost man of his party in the South.” He certainly did provide leadership to his native area in a time of great change and turmoil. The strife in the aftermath of the Civil War was something Judge Thomas Settle, Jr. had sought to avoid. He expressed this aspiration in the Spring Garden speech: “Our thoughts and hopes should be on the future,” he urged his listeners. He wanted to see the South develop and thrive. “This is the land of my birth,” he told his neighbors. “I do not propose to leave it.” “My children are here, and I wish them to have a government fit to live in.” He worked in the decades after the Civil War to bring about such a government, supporting the legal and political rights of all. References

Thomas Settle, Jr., “1867 Spring Garden Political Speech,” Folder 27, Boyd-Settle Collection, Rockingham Community College Historical Collections, Gerald B. James Library, Wentworth, North Carolina; Bob W. Carter, “A Biographical Sketch of Thomas Settle, Jr., and His Family,” Journal of Rockingham County History and Genealogy, XXVII No. 2 (December 2002), 97-114; Jeffrey J. Crow, “Thomas Settle, Jr., Reconstruction, and the Memory of the Civil War,” Journal of Southern History 62, no. 4 (November 1996): 689- 726 (Settle’s testimony before Congress 708), http://www.jstor.org/stable/2211138 (accessed January 5, 2018); Levi Branson, Branson’s North Carolina Business Directory, [1867-1869], LXXXVIII, Digital NC, North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC. https://lib.digitalnc.org/record/25522?ln=en, 96-98, 135 (voters in Rockingham County); Branson, Branson’s North Carolina Business Directory [1869], Rockingham County, 137-139; all counties, 9-172, https://lib.digitalnc.org/record/25524?ln=en ; Michael Perdue, “Historical Sketch of Rockingham County Government,” and “Directory of Officials of Rockingham County, North Carolina 1786-1991,” Journal of Rockingham County History and Genealogy 16 (December 1991): 75, 51-52, 53-89. Bob Carter, phone interview with author, May 30, 2018; Lindley S. Butler, “Thomas Settle, Jr.,” NCpedia, Government and Heritage Library, State Library of North Carolina, https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/settle-thomas-jr; Charles D. Rodenbough, Settle: A Family Journey through Slavery (Columbia, SC: lulu.com, 2013), 105-135; “Death of Hon. Thomas Settle,” Greensboro (NC) North State, December 6, 1888; Journal of the Constitutional Convention of the State of North Carolina, at Its Session 1868 (Raleigh: Joseph W. Holden, Convention Printer, 1868), 104, Electronic Edition, Documenting the American South, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, http://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/conv1868/menu.html; W. P. Bynum, “Condensed Address delivered upon presentation of Settle portrait to Supreme Court of North Carolina, November 7, 1905,” in Bettie D. Caldwell, Founders and Builders of Greensboro, 1808-1908, Fifty Sketches (Greensboro, NC: Jos. J. Stone & Company, 1925), 229-236, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, http://libcdm1.uncg.edu/cdm/ref/collection/ttt/id/17204; Allen W. Trelease, White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1971), 192, 195; Letter from Thomas Settle, Jr. to Albion W. Tourgée, May 12, 1869, Reel 9, Item 1472-L74, Albion W. Tourgée Papers, Microfilm, University of North Carolina at Greensboro; “Justice Albion W. Tourgée to Senator Joseph C. Abbott, May 24, 1870,” New York Tribune, August 3, 1870, in Undaunted Radical: The Selected Writings and Speeches of Albion W. Tourgée, eds. Mark Elliott and John David Smith (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press), 47- 51; Mark Elliott, Color-Blind Justice: Albion Tourgée and the Quest for Racial Equality from the Civil War to Plessy v. Ferguson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 156-159; Albion W. Tourgée, A Fool’s Errand, by One of the Fools (London: George Routledge and Sons, 1883), 212, 219, 220; Letter from Albion W. Tourgée to Thomas Settle, Jr., June 24, 1869, Folder 4, Thomas Settle, Jr. Papers, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Letter from Thomas Settle, Jr. to Albion W. Tourgée, September 7, 1870, Reel 9, Item 1472-168, Albion W. Tourgée Papers, Microfilm, University of North Carolina at Greensboro; Letter from Thomas Settle, Jr. to Albion W. Tourgée, August 1870, Reel 10, Item 1575-L116-117, Albion W. Tourgée Papers, Microfilm, University of North Carolina at Greensboro; Letter from Thomas Settle, Jr. to Albion W. Tourgée, August 30, 1870, Reel 10, Item 1575-L121-122, Albion W. Tourgée Papers, Microfilm, University of North Carolina at Greensboro; Letter from Nettie Settle to Thomas Settle, Jr., November 15, 1871, Boyd-Settle Collection, Folder 26, Rockingham Community College Historical Collections, Gerald B. James Library, Wentworth, North Carolina; Letter from Mary Settle to Thomas Settle, Jr., June 25, 1871, Mulberry Island (Wentworth) to Lima, Peru, Thomas Settle Jr. Papers, Folder 5, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. After Robert Gwynn, the next African American Rockingham County Commissioner to serve was Clarence Tucker, who was elected in the late 1970s. For analysis of the Reconstruction era, see the seminal work of Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 (New York: Harper Perennial, 2014) and Allen W. Trelease, “Reconstruction: The Halfway Revolution,” in The North Carolina Experience, eds. Lindley S. Butler and Alan D. Watson (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1984), 285-307.

3 Comments

Carole W. Troxler

7/10/2021 06:01:56 pm

Great article. Thanks for putting it "out there."

Reply

Sophelia

9/8/2021 03:10:20 pm

Like to be responsible for keeping the up keep on cementary. Thomas Settle Sr.& Mrs Henrietta down on Brooks Rd as you get ready to come down the hill on the left /part of Mrs Nettie's Wright's farm house still standing the tobacco barn just fell in.

Reply

Don Simmons

12/15/2021 08:38:43 pm

! enjoyed this article very much. I would add that the property where the Gwynn Schoolhouse was located was deeded to the county school board by James Thomas Sr. Don

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Articles

All

AuthorsMr. History Author: Bob Carter, County Historian |

|

Rockingham County Historical Society Museum & Archives

1086 NC Hwy 65, Reidsville, NC 27320 P.O. Box 84, Wentworth, NC 27375 [email protected] 336-634-4949 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed