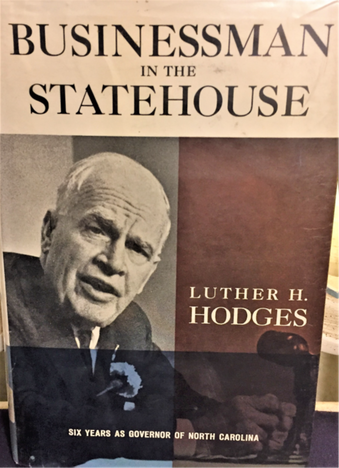

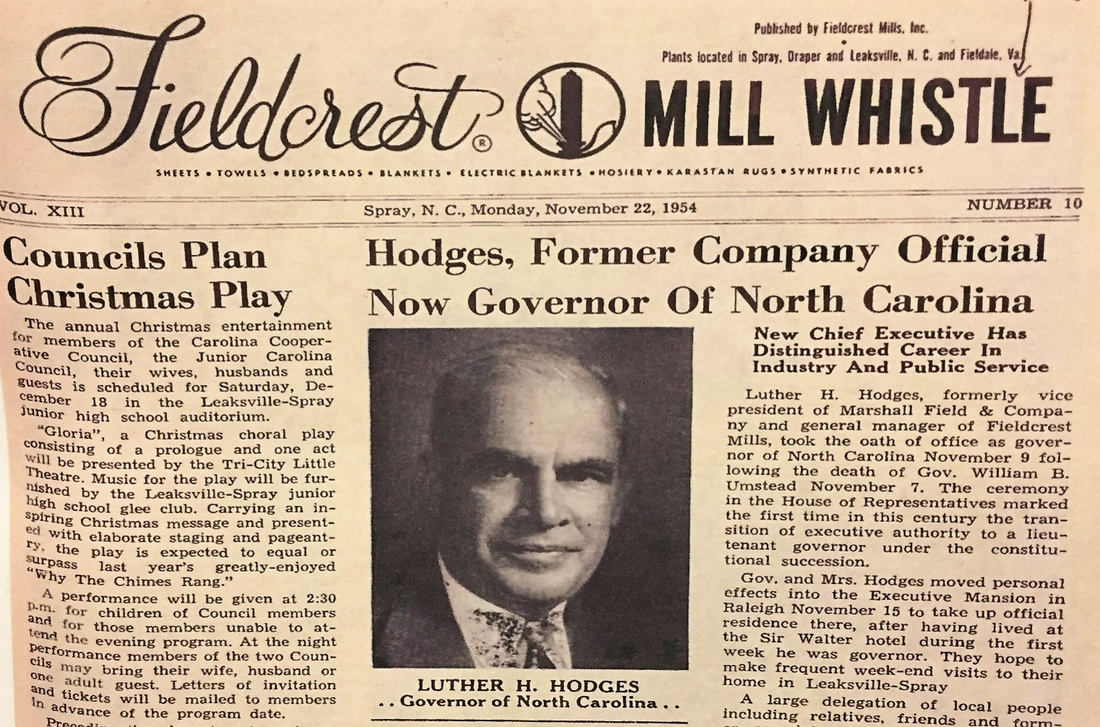

November 1954In November 1954, Rockingham County businessman Luther H. Hodges became Governor of North Carolina. He was at his home in Leaksville on Sunday morning, November 7, 1954, when he learned that Governor William Umstead had died unexpectedly. Hodges, who had been elected the state’s Lieutenant Governor in 1952 in his first run for political office, recalled in his memoir that he “prayed there in that chair” upon receiving the call, and then went on to worship services at his home church, Leaksville United Methodist. There was a “solemn” tone in the Hodges home that morning. In a very personal account, Mrs. Martha Hodges reported that her husband “broke down and cried” at the news and the realization of the “burdens he will now have to bear.” Local people who attended the governor’s inauguration later that week included textile executives and bosses—Harold W. Whitcomb, B.C. Trotter, R.H. Tuttle, and J.E. Barksdale—as well as the superintendent of the local schools and longtime Hodges associate, John Hough. Governor and Mrs. Hodges lived during the first week of his term at the Sir Walter hotel in Raleigh and moved into the Governor’s Mansion on November 15. Certainly, Hodges and other state officials faced challenging circumstances in 1954. In his short tenure, Governor Umstead, who continually dealt with his own health issues resulting from a heart attack he experienced only three days into his term, also had to appoint replacements for both of North Carolina’s Senators who died during this time. No doubt the most crucial issue for state leadership that year was determining how the state would respond to the Supreme Court decision of May 17, 1954, in Brown v. Board of Education. The year became even more daunting for state leaders when Hurricane Hazel, one of the region’s worst hurricanes in history, cut a destructive path northward through the state on October 15. In none of these crises, however, had Umstead called on Lieutenant Governor Hodges for input. In fact, by many accounts, the two had a very chilly relationship. Therefore, the Leaksville industrialist so new to politics had to step into a role for which he had little or no experience. As Lieutenant Governor, an office he had sought as an outsider, Hodges had overseen just a single session of the NC Senate. His home county constituency, however, was enthusiastic and confident in his potential. “The Tri-Cities [Leaksville, Spray, Draper] are proud to have Luther H. Hodges as chief executive of North Carolina,” the hometown paper reported, “and feel that he will conduct the office in a businesslike manner and make one of the best governors our state has ever had.” After more than thirty years as a textile manager and executive, Hodges had run for the office, offering himself as a non-politician and a successful businessman who could apply the same effective practices to government. At a time when the area’s mills were booming, citizens in his home county of Rockingham could have strongly supported Hodges’s record of leadership in textiles, as he had risen through the ranks at Marshall Field, from an office boy at age twelve, to local personnel manager, and ultimately to corporate executive. At the height of his career, Hodges oversaw twenty-nine mills in six states and three countries.  (Cover of the 1962 memoir of Governor Luther H. Hodges) (Cover of the 1962 memoir of Governor Luther H. Hodges) Back in Raleigh, Hodges got to work on pressing matters and wisely retained all of the former governor’s staff. He also inherited Umstead’s Advisory Committee on Education, called the Pearsall Committee, organized to craft the state’s response to the Supreme Court mandate to eliminate racially segregated schools. In race relations, Hodges firmly supported segregation as North Carolina’s official policy. He saw himself as a “manager” of the situation and was considered by many as a moderate, as he called for maintaining the status quo of segregation and promoted the state as a calm place where it was safe and even desirable to conduct business. In political office, Hodges was primarily interested in raising the incomes of North Carolinians and recruiting new businesses to the state, and during his six years as governor, he was able to accomplish many of his goals in this regard. Hodges wrote in his memoir, Businessman in the Statehouse, that his overall interest when he was “catapulted” into the office of Governor was to “do a conscientious job.” During a crucial time for the state and the region, he put key people in place and established policies that heavily influenced North Carolina’s economic and racial politics for decades. The home area of Rockingham County was deeply invested in the success of the new governor. The entire county, and especially the Tri-Cities area, was exceptionally well connected to state government through Hodges, who had retired to his hometown of Leaksville in 1950 after a very successful career as a textile executive with worldwide Marshall Field operations. Many had known him for decades as a business leader. The newspaper in Madison, on the western side of the county, confirmed in announcing the new governor’s taking the oath of office: “Hodges has many warm personal friends in Madison where he is well known. During his many years as manager of the Fieldcrest Mills his various civic activities frequently brought him to the community.” Scores of local folks also attended the Methodist church with Hodges and had served with him in Rotary International, an organization that Hodges had led locally and at the district level and would ultimately lead as global president. Governor and Mrs. Hodges returned to their home county frequently during their six years in the state Executive Mansion, while area residents relished their strong connections to Governor Luther H. Hodges, “a distinguished fellow townsman.” References:

Luther H. Hodges, Businessman in the Statehouse: Six Years as Governor of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1962), 1, 2, 6, 21-22, 80; “Hodges, Former Company Official Now Governor of North Carolina,” Fieldcrest (Spray, NC) Mill Whistle, November 22, 1954, 1, 8, DigitalNC, North Carolina Newspapers, https://www.digitalnc.org/newspapers/the-fieldcrest-mill-whistle-spray-n-c/; Rob Christensen, The Paradox of Tar Heel Politics: The Personalities, Elections, and Events That Shaped Modern North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 157, 162; “Citizenry Speak Highly of Gov. Hodges,” Leaksville (NC) News, November 11, 1954, 1; “Hodges Goes to Church after News of Death,” Leaksville (NC) News, November 11, 1954, 1; “Family and Townspeople See Ceremony,” Leaksville (NC) News, November 11, 1954, 1; “Rockingham Man Sworn in as Governor of State, The (Madison, NC) Messenger, November 11, 1954, 1; “McMichael Re-Elected Executive Chairman of County’s Democrats,” Reidsville (NC) Review, May 17, 1954, 1; Tom Eamon, The Making of a Southern Democracy: North Carolina Politics from Kerr Scott to Pat McCrory (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 39, 42, 44, 53-54; Letter from John Hough to Luther H. Hodges, July 25, 1952, Luther Hartwell Hodges Papers, Box 148, Folder 1755, Southern Historical Collections, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; “Elected Director of Rotary International at Paris, France,” Leaksville (NC) News, June 4, 1953, 1; Charles Dunn, “Luther Hartwell Hodges,” NCpedia, State Library of North Carolina, https://ncpedia.org/biography/hodges-luther-hartwell; Luther H. Hodges, “The Segregation Problem in the Public Schools of North Carolina: Summary of Statements and Actions by Governor Luther H. Hodges,” Pamphlet, March 26, 1956, 6, Box 148, Folder 1753, Education: Integration, Hodges Papers, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; “Dedication Program,” Tri-City High School and Morehead Stadium, February 27, 1953; Superintendent John Hough, “In Retrospect, Progress Report of the Leaksville Township Schools from July 1, 1947 to Jan. 1, 1953.” Only five days before the Brown decision, Senator Clyde Hoey died in office. In support of their native son, Democrats in Rockingham County met and endorsed Luther H. Hodges for the position. In a surprise move, however, Umstead chose Sam J. Ervin, then a member of the North Carolina Supreme Court, for the Senate seat, one Ervin would hold for the next two decades. Umstead had already surprised pundits with his selection of Alton Lennon, a Wilmington attorney, to replace Senator Willis Smith, who had died in June 1953.

3 Comments

8/8/2024 02:00:08 pm

Wonderful post. and you Nice used words in this article and beautifully post it.

Reply

8/8/2024 02:01:34 pm

Such a great word which you use in your article and article is amazing knowledge. thank you for sharing it.

Reply

8/8/2024 04:54:42 pm

Who consistently managed his own medical problems coming about because of a respiratory failure he encountered just three days into his term, likewise needed to choose swaps for both of North Carolina's Congresspersons who kicked the bucket during this time.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Articles

All

AuthorsMr. History Author: Bob Carter, County Historian |

|

Rockingham County Historical Society Museum & Archives

1086 NC Hwy 65, Reidsville, NC 27320 P.O. Box 84, Wentworth, NC 27375 [email protected] 336-634-4949 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed